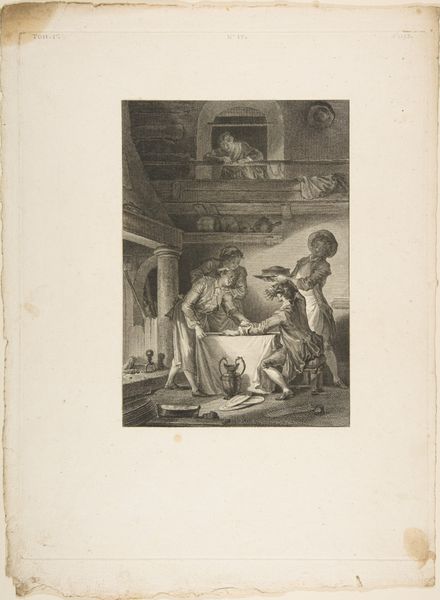

Herberginterieur met een vrouw met baby voor een haard, een staande man voor haar 1788

0:00

0:00

jeandambrun

Rijksmuseum

drawing, etching, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

etching

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

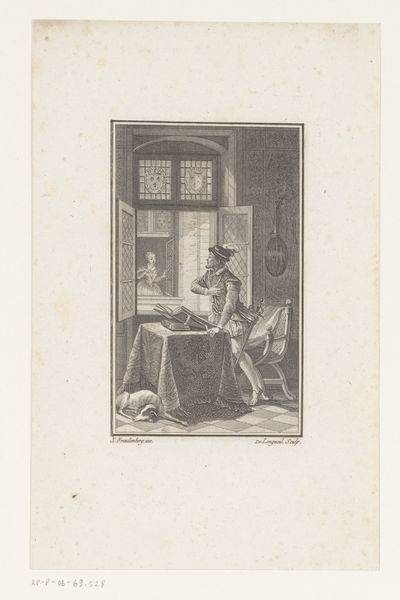

Dimensions: height 193 mm, width 123 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

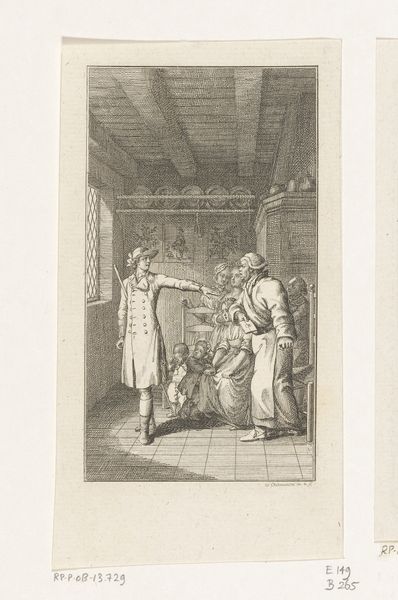

Curator: This is "Herberginterieur met een vrouw met baby voor een haard, een staande man voor haar," or "Tavern Interior with a Woman and Baby Before a Hearth, with a Standing Man Before Her." It's a genre scene made around 1788 by Jean Dambrun, utilizing engraving and etching techniques. Editor: It has a certain quaint charm, doesn't it? The composition, enclosed in that tight rectangular frame, gives it an almost claustrophobic feel, drawing the eye into the domestic space. Curator: Absolutely. I find it compelling how Dambrun situates this scene within a broader narrative of domestic life and class relations in 18th-century society. Note how the setting seems almost sparse, save the clothing. Consider how gender and labor intersect here: the woman with the child, seemingly confined to this interior, while the man, presumably, engages in labor outside the house. Editor: The lines are so precise. You can trace Dambrun's method in how light defines form in that small area he chooses to frame—it gives volume and depth despite the bare means. The artist employs an array of etched lines, but I cannot shake the impression that there's a subtle emotional element, almost sentimentality, emanating from the print. Curator: Exactly, consider the baby and mother—likely lower-class. Dambrun might use this genre scene to subtly highlight their status, possibly inviting sympathy or awareness among viewers of his time. Think about the male gaze implied within the depiction. Does this image serve as an exercise in power, where those in the higher-class bracket can gaze at the unfortunes of people within the lower-class status? Editor: Perhaps. However, from a formal perspective, consider the way he balances the composition: the standing man on one side, counterweighted by the seated woman and child, further complemented by the ancillary figures and objects in the background. I like that Dambrun’s organization holds these figures without it appearing busy. It speaks to an ordered and somewhat stylized treatment, perhaps referencing some sort of aesthetic sensibility, even through what you consider the poor. Curator: It makes me wonder about the intended audience. Were these prints circulated among the bourgeois, offering a glimpse into lives both familiar and alien to their own? What impact did these depictions have on societal perceptions and the construction of class identity during the era of Neoclassicism? Editor: Questions I don't think an art historical approach to mere aesthetics can fully flesh out! I was too focused on form, technique, composition—you provided vital sociopolitical considerations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.