print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

# print

#

sketch book

#

landscape

#

photography

#

personal sketchbook

#

coloured pencil

#

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

pen and pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

watercolour illustration

#

academic-art

#

sketchbook art

#

watercolor

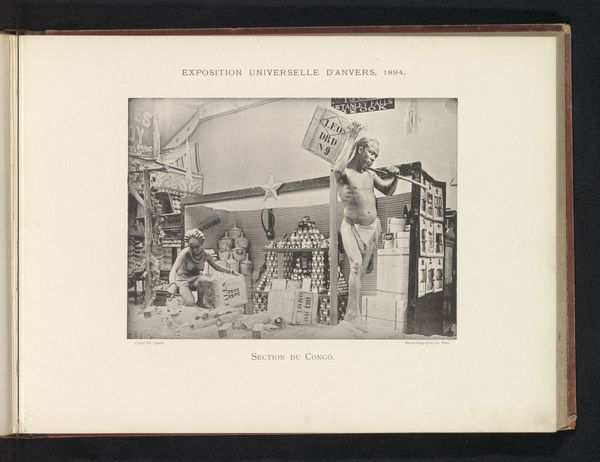

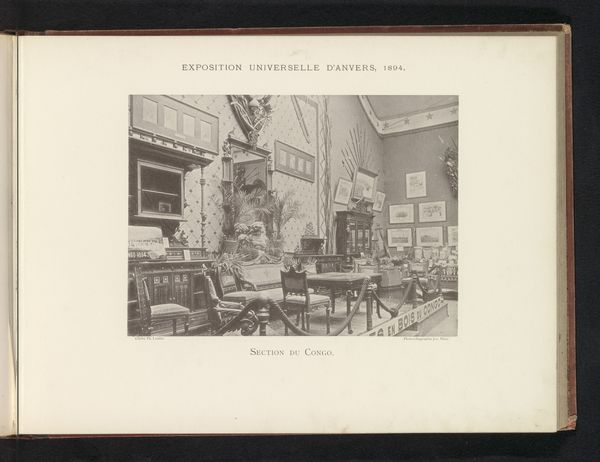

Dimensions: height 159 mm, width 219 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

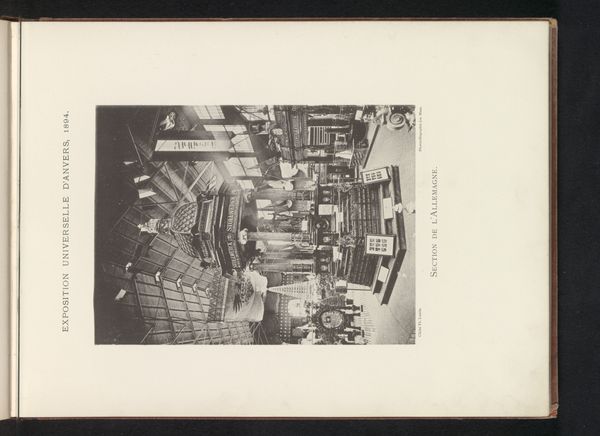

Curator: This gelatin silver print, captured by Th. Lantin in 1894, is titled "Congolese objecten tijdens de wereldtentoonstelling te Antwerpen," or "Congolese objects during the world exhibition in Antwerp." What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It's immediately unsettling. The composition feels staged, almost a caricature. The juxtaposition of the seemingly overloaded figure and the backdrop…it raises so many questions about power and representation. Curator: Absolutely. The photograph documents a display within the Antwerp World's Fair. These world exhibitions were products of their time, deeply entwined with colonialism. Consider the image: a Black figure carrying crates and in the background figures that appear to be Congolese people on display behind some storefronts. Editor: It’s blatant objectification. The figure seems to be literally burdened by the weight of colonial goods, becoming a symbol of exploited labor. And that word “Section.” This reinforces the division of people as specimens within an imperial project. I'm interested in the figures in the background--they lack agency, positioned merely as decoration. Curator: Right. The exhibition served as a platform to legitimize Belgium’s colonial ventures, particularly under King Leopold II. We must acknowledge the role of photography in constructing a skewed narrative about Africa and its people. Consider the broader historical context: this fair was happening amidst the atrocities in the Congo Free State, under Leopold’s brutal regime. Editor: And how complicit was the photographic image itself in perpetuating these injustices? This print, like so many others, reinforces the image of the "other" – exotic, subjugated, and commodified for Western consumption. It underscores the power dynamic inherent in the gaze, who is looking at whom and for what purpose. Curator: It's a powerful reminder of the complexities and contradictions inherent in our historical record. Art serves as a conduit through which we confront difficult truths and reimagine our understanding of the world. Editor: I agree. Engaging with works like this helps us unpack the historical and continuing implications of colonial representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.