#

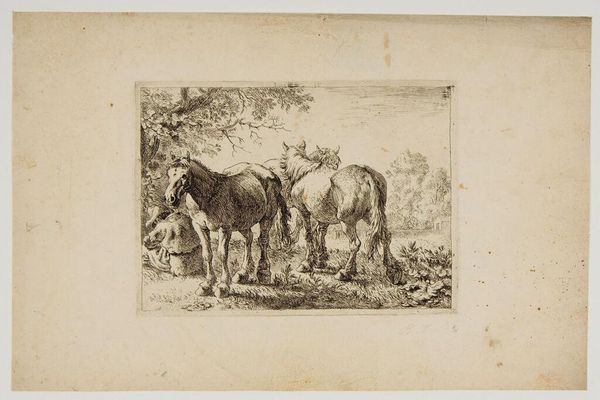

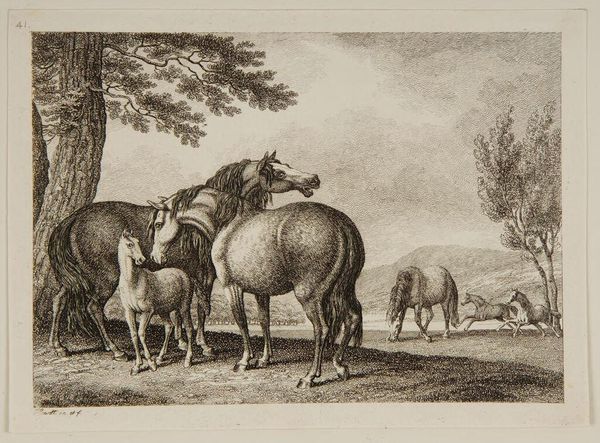

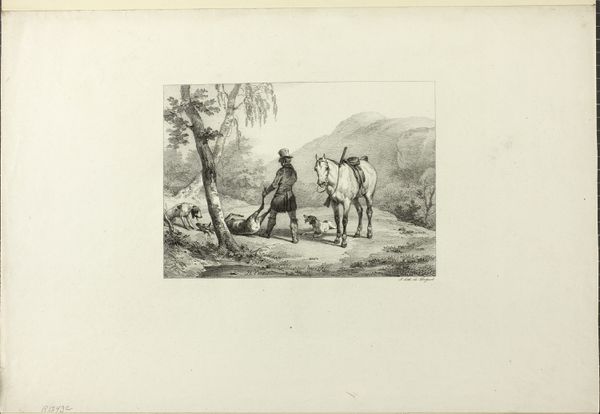

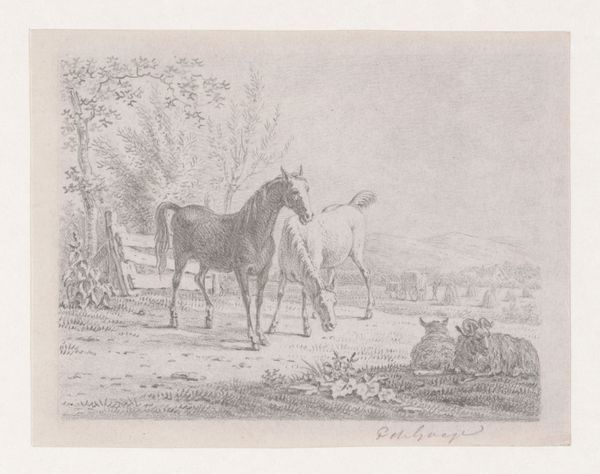

pencil drawn

#

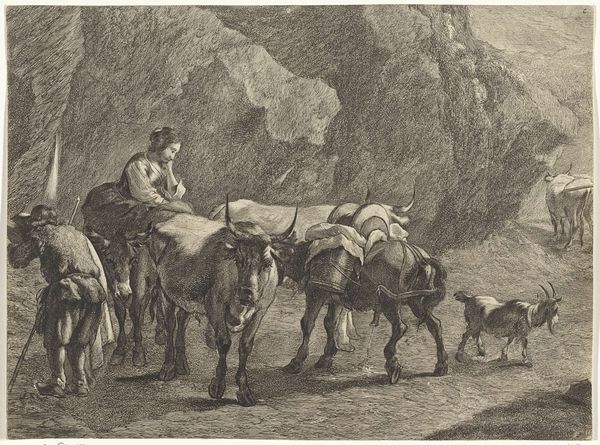

photo of handprinted image

#

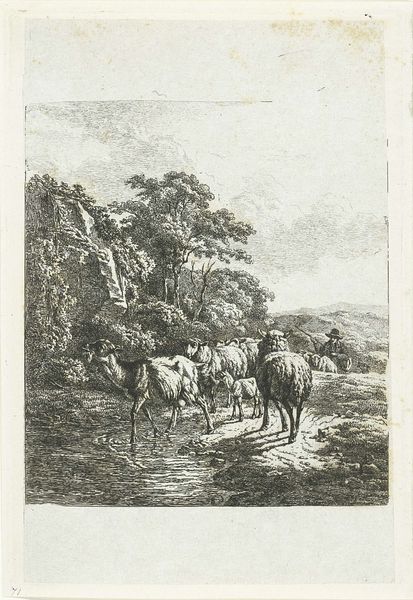

amateur sketch

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

incomplete sketchy

#

pencil drawing

#

pen-ink sketch

#

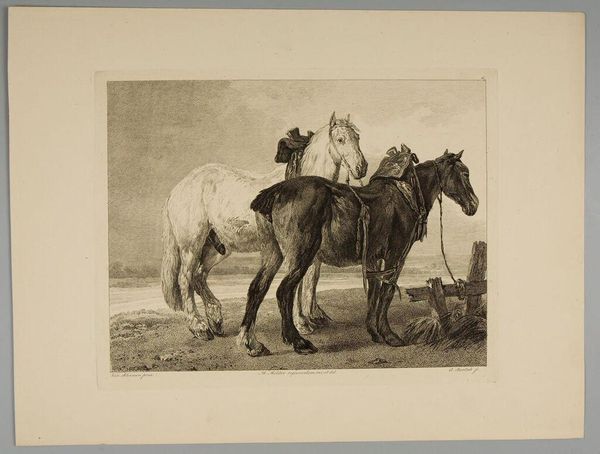

pencil work

#

remaining negative space

Dimensions: height 187 mm, width 226 mm, height 250 mm, width 335 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

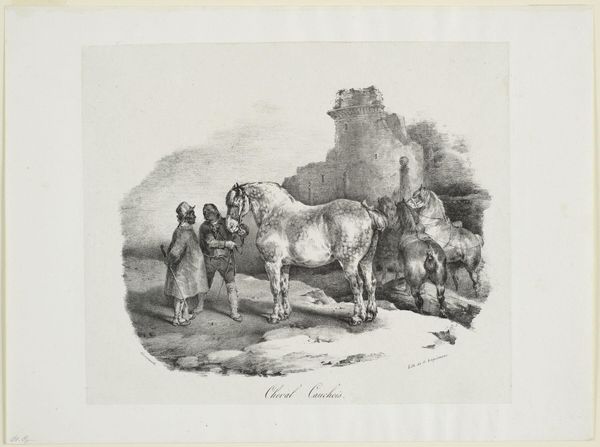

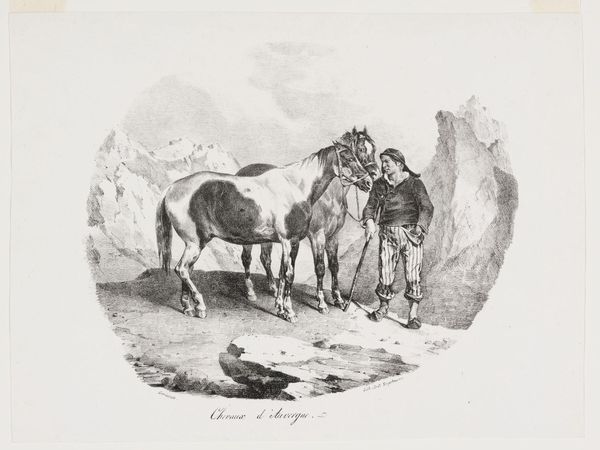

Curator: Well, it’s a bit stark, isn't it? Immediately draws the eye to the strong musculature of the horse. Editor: Indeed. Here we have Théodore Géricault’s “Normandische Cob,” created around 1822. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. It is stunning when thinking about Géricault’s position in shaping early 19th-century French Romanticism. Curator: I see an emphasis on labor – you've got these handlers, dressed plainly. Not gentry. It feels deliberately unglamorous, despite the horse's obvious power. What are the labor conditions around equestrian art during this period? Editor: Exactly. It marks a fascinating shift from idealized equestrian portraits. Consider how the Industrial Revolution affected equine labor and depictions thereof. The art market catered largely to the upper classes; these individuals consumed images to promote themselves within their society. How did the imagery need to be reconfigured given Géricault’s changing audience? Curator: Good question. There’s definitely a rawness to the lithographic pencil work that speaks to the actual handling and breaking of these powerful animals. Notice how he renders them with that incomplete sketch, remaining negative space—highlighting the horse's robust form, its raw, almost untamed energy through its visual production. Editor: It feels almost political, the focus on the working relationship between humans and animals, within the context of post-Revolutionary France. The printing, available for a wide public to experience, gives insight into changing public appreciation of working relationships and animal consumption in the labor sphere. Curator: What gets me is that unfinished quality juxtaposed with the animal's imposing size. It’s about capturing not just an image but also the social conditions of the working animal in contrast to high-art depictions. Editor: Definitely, it invites discussion on evolving tastes, as society reconsiders its relationship to the labor behind the products we admire and how its depiction changes within artworks. It prompts contemplation on the artist's evolving role during this shifting socio-political climate. Curator: I leave thinking differently about the process of domestication and the artistic methods used to show them to a broad audience, quite impressive. Editor: I concur. Thinking about Géricault and the implications of such material really makes us reassess the way the public views artistic movements as they appear in history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.