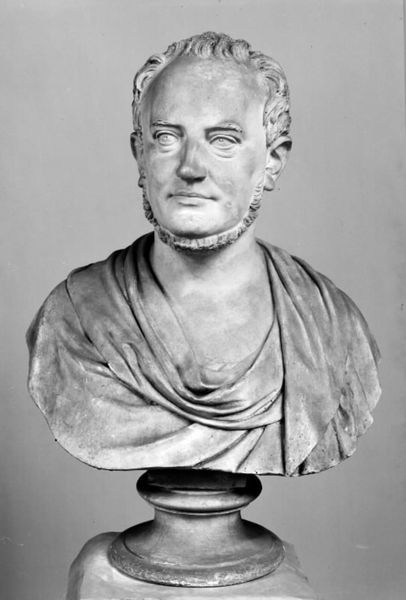

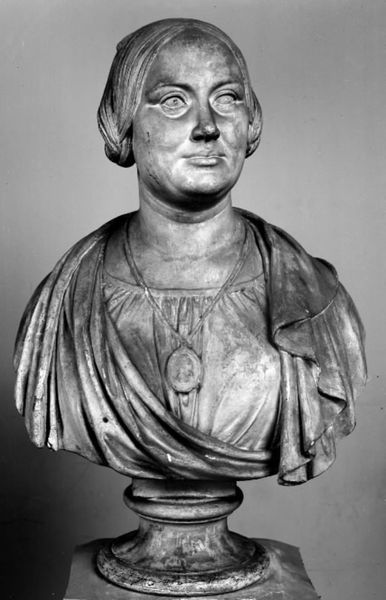

Dimensions: 72.7 cm (height) (Netto)

Editor: This marble bust, "Grev Preben Bille-Brahe," was sculpted by H.W. Bissen in 1866. The subject’s stern expression definitely caught my attention. What’s your perspective on this classical piece? Curator: Well, beyond the representation, I’m immediately drawn to the labor embodied in this object. Marble doesn't just *become* a likeness. The sheer physical effort required to extract, transport, and carve such a dense material into a form exhibiting Neoclassical ideals of power and permanence is substantial. Consider, too, who had access to such skilled labor in 1866, and how that impacts our reading of the subject's stern countenance. What social strata afforded one such portraiture? Editor: That's interesting. I hadn't really thought about the labor involved, just the artistry. So, are you suggesting the marble itself is a marker of wealth and status, just as much as the Count’s features? Curator: Precisely. Marble was a commodity, controlled by specific economic and political forces. Bissen's access to it, and his technical skill, also positions him within a specific system of patronage and artistic production. Think about how this contrasts with, say, folk art created with readily available, local materials. Editor: It does put a different spin on the traditional portrait. It's not just about capturing likeness but about the material realities of its creation. Curator: Absolutely. Examining the materiality of art forces us to consider the means of production, the consumption of resources, and the social hierarchies inherent within those processes. It re-situates high art within the broader scope of craft and labor. Editor: That definitely changes how I'll look at sculptures from now on. There's so much more to see than just the surface. Curator: Indeed, and it prompts us to question whose stories get told through these meticulously crafted objects.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.