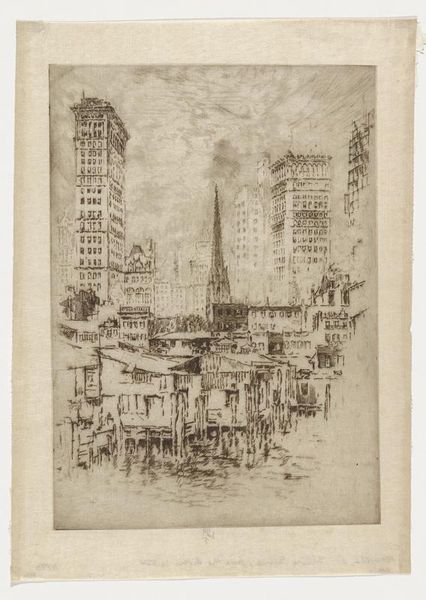

print, etching

# print

#

etching

#

etching

#

cityscape

#

modernism

#

realism

Dimensions: 9 15/16 x 7 15/16 in. (25.24 x 20.16 cm) (plate)13 1/2 x 10 5/16 in. (34.29 x 26.19 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: No Copyright - United States

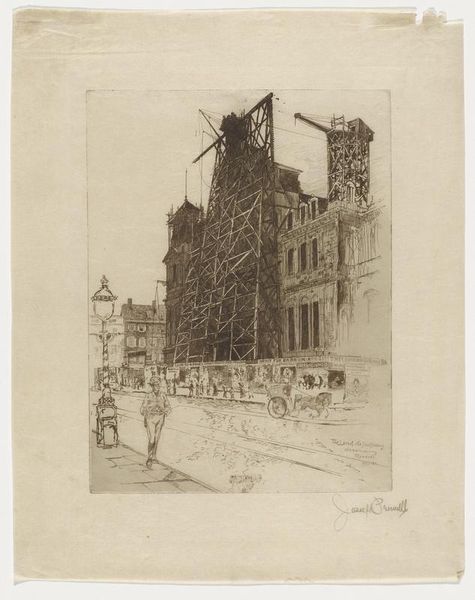

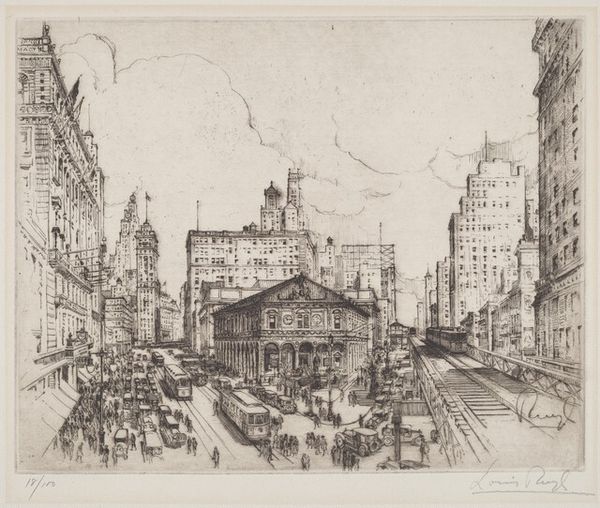

Curator: This etching, entitled "Twelfth Street Meeting House," was created around 1920 by Joseph Pennell, now residing at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Editor: My initial feeling is of constraint, almost claustrophobia. That squat, low building is completely overshadowed, visually bullied by the looming skyscrapers around it. Curator: Well, let’s consider Pennell's materials and method. The delicate lines of the etching process create this incredible tension, highlighting the textures of both old and new construction. It seems the very *process* emphasizes the building’s humble construction against the steel giants. Editor: And that placement, at eye level! Pennell seems intent on documenting urban development and societal shift. By rendering the Meeting House—a place presumably of peace, community, and reflection—amidst looming commercial architecture, it speaks volumes about the prioritization of profit and progress. How do historical preservation efforts factor into our cultural identity and our relentless pursuit of new markets and resources? Curator: It's an astute observation; notice also Pennell’s choice to emphasize the craftsmanship embedded in these architectural forms. It is not about pure aesthetics; we are looking at human-scale labor materialized in steel and stone and brick, consumed within larger forces. Pennell's technique is crucial to his artistic choices in portraying labor, architecture, and industry. Editor: Right, but think about how it comments on the people *affected* by such shifts, those in and around that meeting house—their values potentially in opposition with a changing world driven by commerce and power. Pennell’s capture feels less about glorifying modernization and more about its disruption of communal life and traditions, especially spiritual practices within community spaces. Curator: Still, while these looming buildings can signal societal oppression or even the weight of commerce, Pennell's rendering still allows the viewer an accessible composition. Even now, that sense of grounded space encourages people to re-consider traditional places within industrialized life. Editor: Maybe, but the print pushes viewers to consider whose voices get heard, whose labor counts. It demands more nuanced questions. And what sacrifices are made in the name of modernity, progress, and urban life? Curator: A poignant interpretation, considering that our engagement with older and traditional crafts and architecture are inevitably consumed within material industries—especially within art, architecture, or real estate. Editor: Absolutely. These buildings, and how we value them, are testaments to our historical memory—or its erasure, depending on whose interests are being served. They spark questions of cultural and socio-political meaning, then and now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.