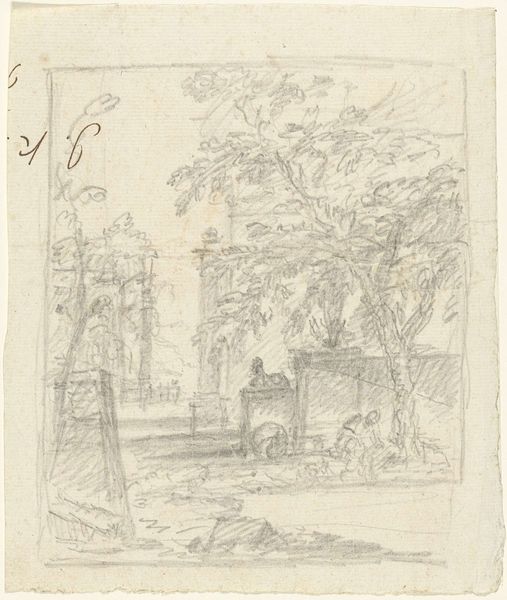

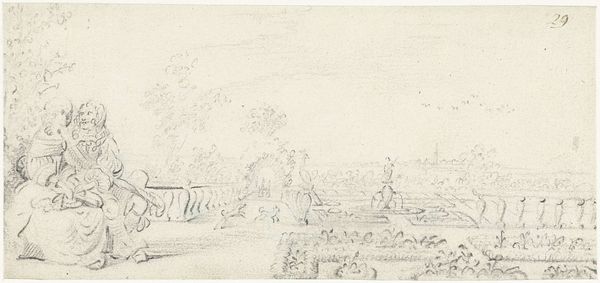

drawing, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

landscape

#

paper

#

pencil

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 197 mm, width 115 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: So, what are your initial thoughts about this tender drawing? I feel instantly transported. Editor: It’s quiet. Reserved, almost. The muted grey of the pencil on paper gives the scene a sense of distance. Before we lose ourselves completely, though, perhaps a word about the artist and the artwork. We’re looking at “Lovers in a Monastery Garden” by Gesina ter Borch, made around 1658. It's a pencil drawing on paper and resides at the Rijksmuseum. Curator: Tender, yes. Quiet, maybe deceptively so. There is something brewing beneath the surface of this demure domesticity. Those arched windows framing what look like groups of figures create a feeling of expectation—perhaps a hint of judgment? Editor: Absolutely. It’s a “genre painting,” they call it, this snapshot of everyday life. But “everyday” for whom, and under what constraints? We see this elegant couple strolling, maybe flirting, in what we're told is a monastery garden. Consider what that space means – a retreat from the world, but also a place of rules, surveillance, gendered exclusion. Were women involved with Dutch Golden Age landscape, given it was considered a "profession" largely dominated by men? Curator: I hadn't thought about it like that! I mean, her works have always moved me for their softness, attention to detail. And maybe I was so preoccupied by how masterfully she captured this airy courtyard in a limited medium that I missed something bigger. Editor: Right, Gesina wasn’t just casually sketching; she was making a claim to visibility, maybe even subtly critiquing social structures. This idyllic scene might be more staged than we assume. Perhaps, as it was also suggested, there is evidence of trauma in her life that influenced her art; the quiet reserved tonality a visual interpretation of said pain? Curator: Trauma interpreted visually as restraint: the artist's brush a muted tool used on a scene that speaks to longing rather than belonging... Perhaps. I tend to over-romanticize such works because I long for an artist retreat to produce my best stuff. But this conversation has given me lots to think about. Editor: Me, too! It's easy to get lost in the details of brushwork, technique, medium—but that is why it’s essential to engage with the sociopolitical contexts that made their artwork, well, work.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.