Copyright: Public domain

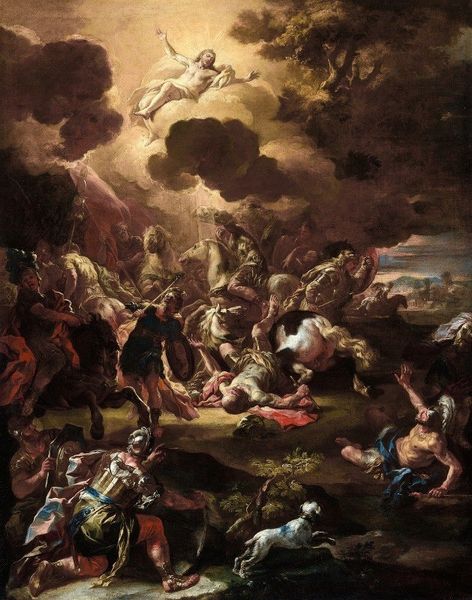

Editor: This is Eugène Delacroix’s “Apollo Slays Python,” an oil painting from 1851. It feels incredibly dynamic, with so many figures swirling around. It’s chaotic, almost, yet my eye keeps being drawn to the center, to that burst of light. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I am immediately drawn to the interplay between the darkness and light. The composition directs the viewer’s gaze toward the dynamic center where Apollo triumphs. Notice how the darker tones around the edges and in the lower register serve to accentuate the brilliance of Apollo and his chariot. Observe the use of diagonals, how they inject energy into the work and prevent the eye from settling. Editor: The diagonal lines certainly make the work feel less static. Is it common to read dynamic movement into works from the Romantic era? Curator: Indeed. Romanticism privileges dynamism and emotion, favoring movement over stillness, and vibrant colors over muted tones. Delacroix is certainly working within that tradition here. Also, note the circular composition—everything seems to emanate from or converge upon Apollo. Editor: So the circular composition, combined with those contrasting light effects, creates an amazing sense of drama. It makes the whole scene seem much larger than life! Curator: Precisely! Delacroix uses these formal techniques—composition, color, line—to convey a sense of the epic and the sublime, characteristic features within the Romantic aesthetic. I find it’s a fine example of a mural within a painted frame to consider and enjoy its full expressive potential. Editor: I hadn’t thought about the importance of formal elements in conveying the grand themes of Romanticism. It's more than just subject matter, isn't it? Thanks for that insight!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.