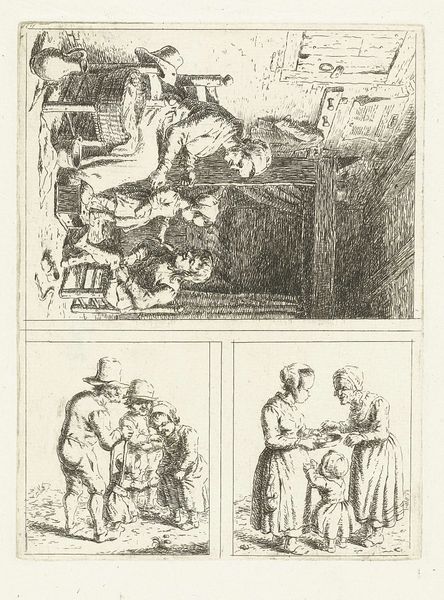

Dimensions: height 159 mm, width 119 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

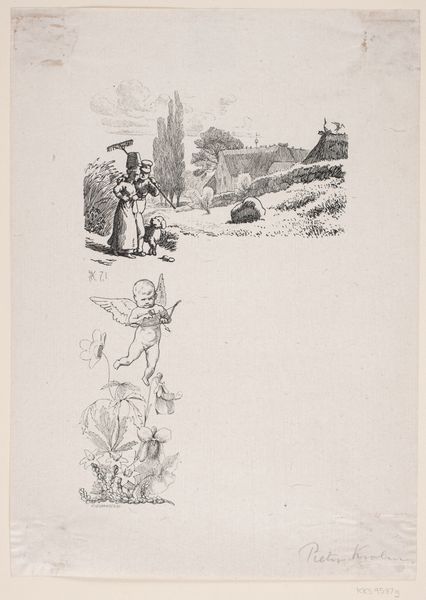

Curator: Here we have Christina Chalon’s etching, "Three Scenes of Family Life," likely made between 1758 and 1808. Editor: It strikes me immediately as an intimate glimpse into 18th-century domesticity, rendered with such delicate lines, almost like sketches from a personal diary. There is a raw, immediate quality to this work, particularly in the depiction of children at play and moments of shared activity. Curator: Chalon created a fascinating tableau of familial existence, indeed. Note how she segments these instances; what could this tell us about 18th century domestic roles and gendered expectations? Editor: I think those separate panels almost act as individual narratives or stories within a larger discourse on family, drawing attention to gender and intergenerational expectations. Look, for example, at the rendering of labor above versus that of simple acts of nurturing below, what can we unpack about women and the feminine role when we contrast such renderings? Curator: I think the placement, the hierarchy, hints towards accepted societal values and power dynamics during the period. The detail, almost ethnographic detail of each panel suggests a narrative – consider how genre painting at that moment sought to moralize everyday life. Do you see something here of that same tenor? Editor: Perhaps. It raises questions about what kind of family life was deemed worthy of artistic representation and public consumption at the time. The idealized simplicity in each panel versus the chaotic detail—is it meant to provide the viewer with a realistic glimpse, or reinforce an already skewed perception of ‘family’? I see echoes of similar visual narratives, only slightly shifted through Chalon’s lens. Curator: True, she complicates rather than complies. Consider also how an etching functions – a print could make such domestic scenes widely available for different tiers of the social classes; this has a socio-political life to it, beyond the simple image itself. Editor: It makes one ponder who got to see what kind of domestic life. And, in turn, who felt invited into or excluded from this intimate sphere as a viewer. What are the performative gestures around class when it comes to something seemingly straightforward such as motherhood and family? Curator: That question of accessibility shifts our perspective on the politics of the domestic even further, don’t you think? Well, thank you. This examination has provided deeper insight to my understanding of the print. Editor: Indeed, it's exciting to see what these 18th-century sketches have to say to modern life and our own contemporary moment.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.