painting, fresco

#

portrait

#

painting

#

figuration

#

fresco

#

christianity

#

charcoal

#

italian-renaissance

#

early-renaissance

#

angel

Copyright: Public domain

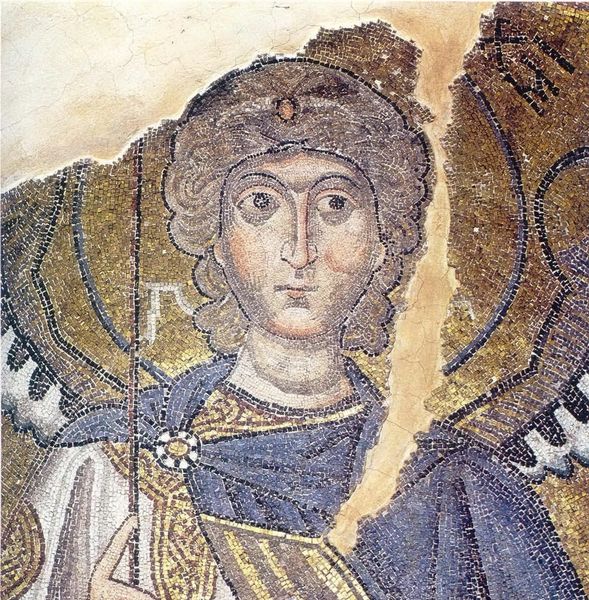

Curator: Standing before us is Piero della Francesca’s "Angel," a fresco dating back to 1452. It resides within the Basilica of San Francesco in Arezzo, Italy, part of his larger cycle depicting the Legend of the True Cross. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is its stillness. The colors, softened by time, create a remarkably serene mood, almost as if the angel is holding her breath. Curator: Absolutely. And look at how Piero uses fresco, painting directly onto the wet plaster. Fresco required speed and careful planning. Each section would be applied one at a time to align to the narrative. Editor: The material process becomes integral to the overall effect; the pigments, lime, and water interacting to create this matte, earthy surface. How does it impact your thinking about gender, race, or politics here? Curator: It brings to mind discussions of Renaissance ideals of beauty and how these informed the perception of marginalized groups. The angel's features, though idealized, still exist within that societal construct, don't they? There is a whiteness assumed in depictions like these. Editor: That's undeniable. Focusing on the tangible realities – the availability of pigments, the local plaster, and the economics of labor that dictated the pace – offers another lens. The halo, for instance: did the artist use precious metals to suggest holiness and how was he sourcing it at this time. What does this say about wealth or poverty in this community? Curator: The placement within the Basilica, alongside scenes of warfare and imperial power, underscores a complex intersection between faith, class, and political agendas, yes? She seems to hover above this intersection and maybe is used to comment or to show some sense of balance within this world. Editor: And balance, in the materiality of it all – balancing speed with permanence when working on the fresco to bring the biblical text into a concrete representation. We can think through social realities if we begin to analyze the real resources or social practices that produced art history. Curator: By situating this artwork in a broader intersectional narrative, we might find resonance and relevance in today’s world in that tension between peace and war that plays on repeat across our communities. Editor: Looking closer at the means of production encourages questioning established narratives; art becomes less about perfect representation and more about reflecting—sometimes unintentionally— the material and social realities of its making.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.