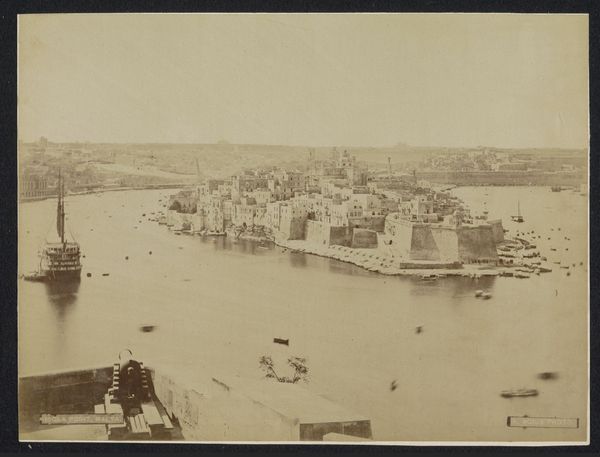

print, daguerreotype, photography

landscape

daguerreotype

photography

orientalism

cityscape

watercolor

monochrome

Dimensions: Sheet: 22 3/8 × 15 5/8 in. (56.9 × 39.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Today, we’re examining “95. Foûah, sur le Nil,” a daguerreotype created in 1843 by Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey. Editor: My first impression is one of ethereal stillness. The monochromatic rendering really amplifies the architectural details reflected in the water; it almost feels suspended in time. Curator: Absolutely, the scene is ripe with early Orientalist aesthetic. Given its time, we have to remember Prangey’s position as a European capturing an image from the Arab world through a colonial lens. His work must be interrogated not just as an objective record but as a subjective construction rooted in prevailing power dynamics and exoticism. Editor: And what makes the image so compelling is its materiality: a daguerreotype is an object. Silver-plated copper carefully prepared. Each one is unique, crafted through a meticulous process tied intimately to the materials and chemistry involved. The labor, the careful handling of these elements underpins the creation of this scene, of Fouah. Curator: Thinking about the materiality in that way gives a glimpse of the world system at the time of its making: industrial production and a fascination with capturing and controlling places through imagery. How are those buildings constructed, what materials went into the making of a city along the Nile, and who are the people implicated in the processes of creating that infrastructure? Editor: That's precisely the context that gives this photograph deeper meaning for me. It’s not just about the captured image, but about understanding what the materials reveal regarding economic and colonial realities. Think of the silver mined to coat the plate, the origins of the lens on the camera itself. It allows us to connect artistic output to labor systems and material flows that are often obscured in traditional analyses of high art. Curator: Exactly, by tracing the history of this image we are implicating ourselves, questioning how such beautiful art is imbricated in political contexts that involve historical and present day modes of subjugation. Editor: To consider photography this early and think through all the labor systems and exploitations inherent within the technology opens another realm of inquiry. Curator: Reflecting on both artistic intent and socio-political structures can hopefully help us appreciate not only this historical artwork but also develop a sensitivity towards those often elided dimensions in more contemporary work. Editor: Absolutely. Seeing how artistic representations arise out of specific material conditions encourages critical examination of all artistic processes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.