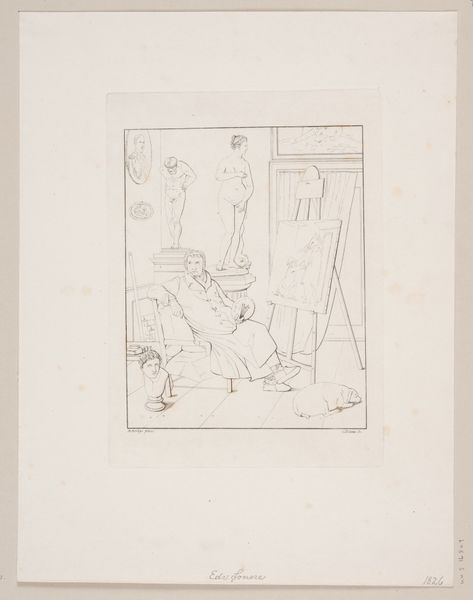

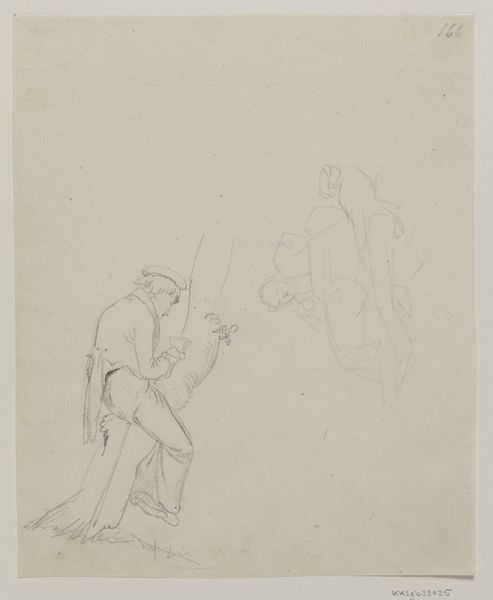

Umgestürztes Standbild in einer Ruinenlandschaft 1829 - 1830

0:00

0:00

drawing, pencil, architecture

#

drawing

#

neoclassicism

#

landscape

#

geometric

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

pencil

#

architecture

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Looking at Friedrich Maximilian Hessemer's pencil drawing from 1829 to 1830, "Umgestürztes Standbild in einer Ruinenlandschaft," or "Overturned Statue in a Ruined Landscape," displayed here at the Städel Museum. Editor: It's haunting, a real sense of desolate grandeur. The classical ruins are sketched with a light touch, yet there's this unmistakable feeling of loss and the weight of history crumbling. Curator: Absolutely. Hessemer, positioned the remnants of what clearly once were icons of power and order, reflects on the cyclical nature of civilizations, the ebb and flow of political regimes. Consider this work in the broader context of the post-Napoleonic era, rife with revolution and shifts in social and governmental structure. Editor: The image of the overturned statue specifically jumps out. The physical act of toppling an idol holds profound symbolic meaning across various cultures and periods. This image reminds me of Shelley's "Ozymandias" the arrogance of power and the inescapable decay that befalls everything. The head, lying on its side… it speaks volumes, or rather, silences volumes. Curator: Precisely, but there’s an architectural figure left standing. Its placement seems deliberate—does it represent a lingering echo of the old order, or perhaps a monument standing sentinel over this changed, or challenged reality? What does that figure represent and memorialize? Editor: Good question. The contrast invites analysis of the value of the statue on its pedestal to that statue abandoned at its base. Was it pride or just plain vanity? There could even be some commentary on the futility of the establishment and its symbolism of absolute power through cultural symbols such as that now prone head. Curator: That reading opens an entirely different line of inquiry when considering today’s conversations around monuments, legacy, and how we collectively memorialize histories. Editor: A simple sketch, yet it captures so much cultural information. Art reveals who we are. It teaches us. Curator: Yes, and it prompts these much-needed conversations and reflections. An important testament.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.