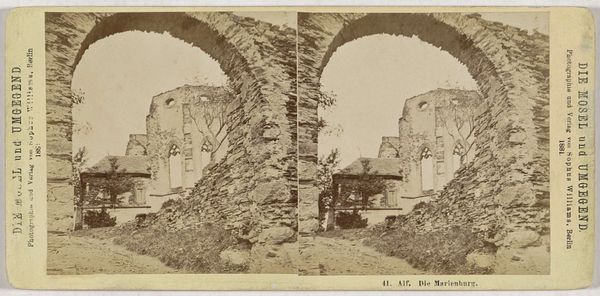

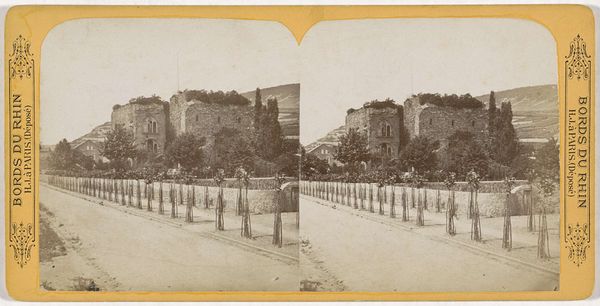

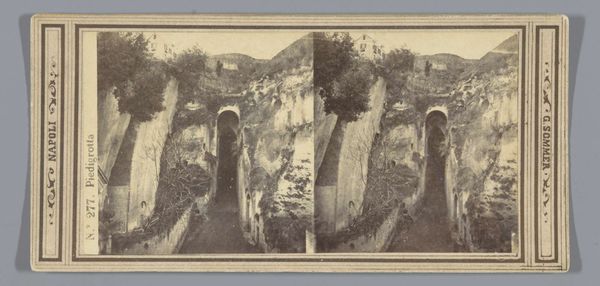

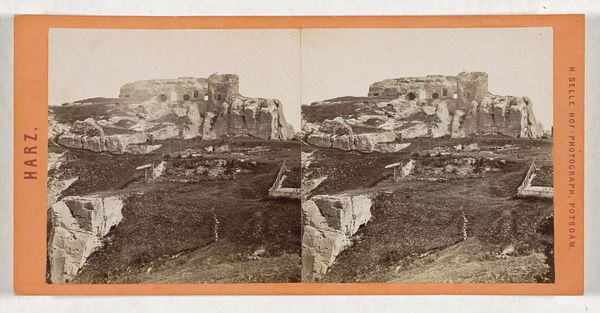

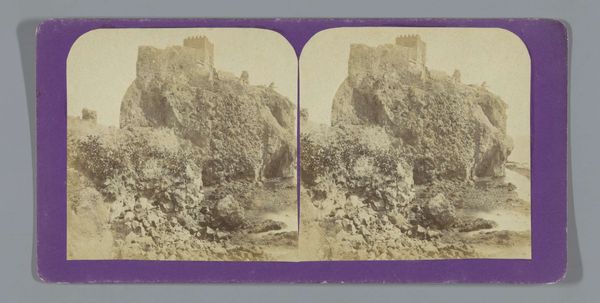

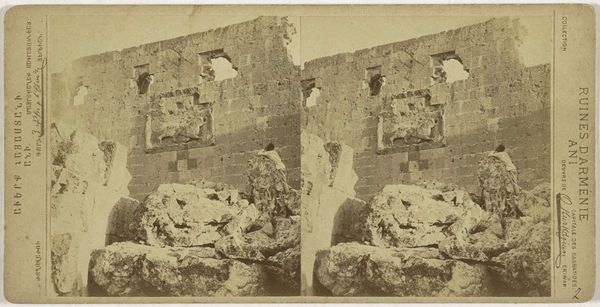

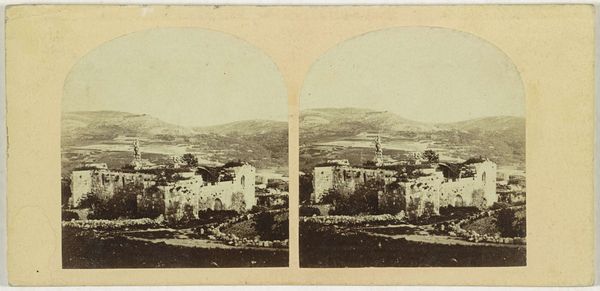

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

cityscape

#

realism

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 174 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is a gelatin-silver print by Francis Frith, created between 1859 and 1861, titled *Roman Aqueduct in Banias, Syria*. The way nature reclaims these ancient ruins is quite striking. What aspects of its history and cultural context are most interesting to you? Curator: What's immediately compelling is Frith’s vision of antiquity. This wasn't simply a documentary photograph; it presents the ruins as picturesque relics, fitting into the colonial era’s romantic view of the “Orient.” Do you think the composition lends itself to a sense of loss, or perhaps something else? Editor: Perhaps a bit of both? The ruins speak of loss, but the overgrown vegetation gives it a sense of resilience too. I wonder, how would the average European viewer interpret this image at the time? Curator: That’s the crux of it. For many, such images fueled the popular Orientalism, evoking a sense of European cultural and technological superiority over the 'decaying' East. Frith was catering to a market eager to consume images that validated a certain worldview. Consider, how does knowing this change your perspective on the work? Editor: It definitely adds a layer of complexity, making me question my initial, purely aesthetic reaction. Curator: Exactly. These early photographs weren’t neutral; they were products of a very specific political and social landscape. Reflecting on this makes it clear the social role art plays, especially regarding imagery and politics. Editor: It's fascinating how photography, seemingly objective, could be so deeply intertwined with the politics of its time. Thanks for showing me how to look at art in a wider social frame. Curator: Indeed. Recognizing the sociopolitical forces behind even seemingly straightforward images is key to understanding the art's full meaning and continued legacy.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.