silver, print, photography

#

yellowing

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

16_19th-century

#

silver

# print

#

white palette

#

possibly oil pastel

#

photography

#

portrait reference

#

underpainting

#

france

#

men

#

watercolour illustration

#

tonal art

#

watercolor

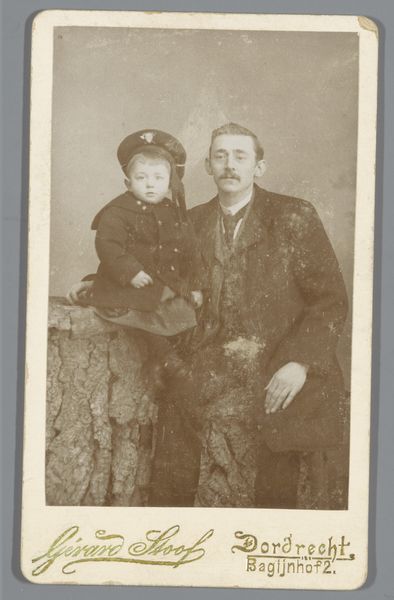

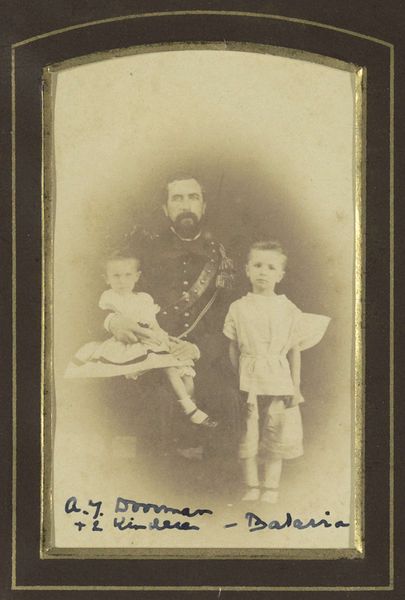

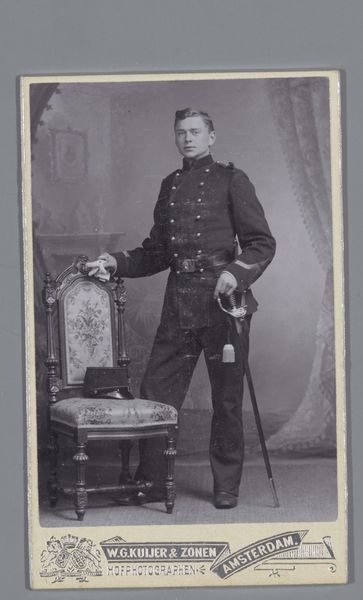

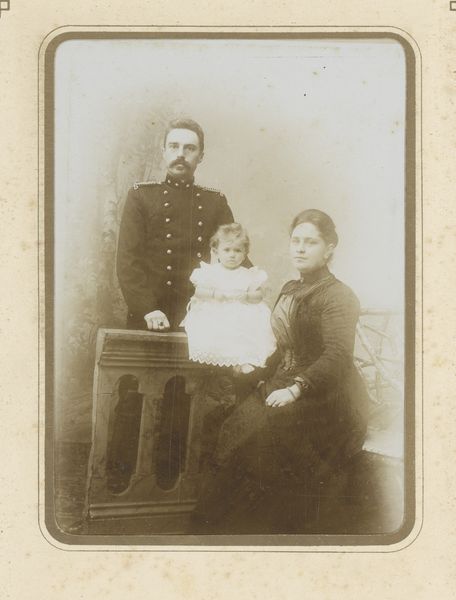

Dimensions: 8.7 × 5.5 cm (image/paper); 10.5 × 6.2 cm (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Immediately, I’m struck by the palpable air of solemnity; they both seem to hold a weight of expectation. Editor: This is "Grand Duke Constantine and Son," a silver print photograph from the 1860s by Verry Fils, now in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. Curator: I see. Well, the tonal range fascinates me; the way the silver print renders fabric – look at the intricate buttons and the deep folds in the Duke's uniform. There's such texture suggested by the controlled use of light and shadow. The hat the duke holds; it's such a display of meticulous, craft production. Editor: The piece resonates powerfully when viewed through a lens of power dynamics. Constantine was a figure deeply enmeshed in the structures of Russian imperial authority. This image, reproduced and circulated, was a tool in constructing and maintaining an image of dynastic strength. How does it normalize power? Look at the child—even his innocence is framed by imperial expectation. Curator: Interesting; so you're thinking about photographic techniques of reproduction being complicit within these displays of aristocratic power? In terms of its consumption and function for public dissemination? That's a far cry from focusing simply on photography's aesthetic qualities. Editor: Absolutely, and in the 1860s, photography's relative accessibility meant these images circulated broadly. The photograph flattens hierarchies even as it reinforces them. These photographic representations, so accessible in one sense, were also tools of exclusion. It begs us to question: whose stories were being circulated, and whose were not? Curator: The photographer’s signature— "Verry Fils"—becomes important here, too. Where were they situated within this whole economy of image-making, this theater of imperial visibility? Editor: Precisely. This image is a quiet, yet powerful, document of an era defined by both vast social inequality and rapidly changing technological means of representation. Curator: I now see the portrait is not only an aesthetic object but an intricate document of manufacture, distribution, and influence. Editor: Yes, by viewing it critically, we gain a glimpse into the visual strategies used to construct and maintain hierarchies.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.