Ruit met architectonische, wapenschild en dier fragmenten en in het midden een jongeman met bokje op zijn schouders 1594

0:00

0:00

drawing, tempera, glass

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

medieval

#

tempera

#

11_renaissance

#

glass

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 71 cm, width 50 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

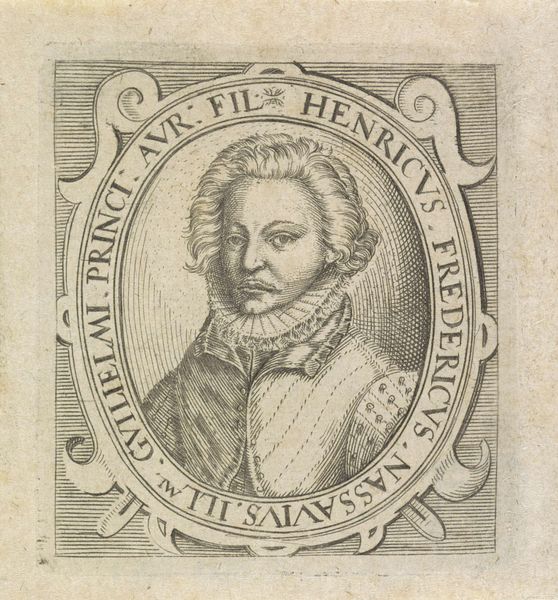

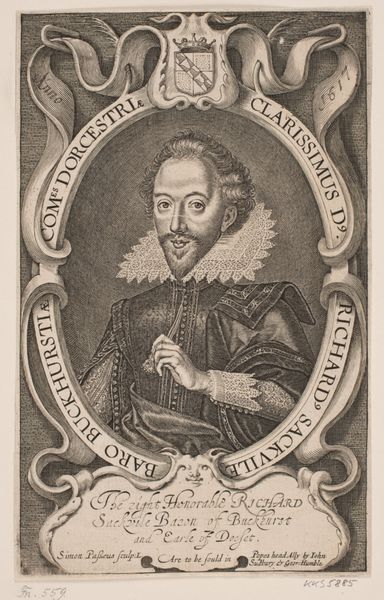

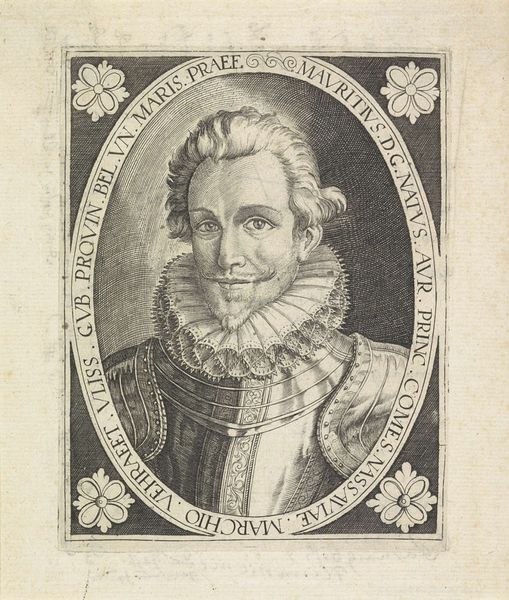

Curator: This remarkable glass panel, created in 1594, is attributed to Claes Abrahamsz. van Delft. It’s titled, rather descriptively, "Ruit met architectonische, wapenschild en dier fragmenten en in het midden een jongeman met bokje op zijn schouders.” The description suggests multiple narrative registers at work, what's your impression? Editor: Striking! There's a directness in the portraiture, even given the stylized, almost heraldic setting. The limited palette—browns, whites, greys—makes me think about how these materials shape its reception today. How would its creators perceive of this effect, or how did it interact with its original environment. Curator: Right, let’s situate the portrait itself. The young man, rendered with such fine detail, framed by elaborate architecture and the hint of heraldry—it speaks to emerging individual identities in the late 16th century, even in spaces previously dedicated to purely religious images. Whose story might be elevated this way? Editor: Absolutely, this elevation also reflects the rise of artisan workshops and their sophisticated glassmaking skills. Think of the process— the labor and knowledge, combining mineral pigments with glass at high temperatures, multiple firing for achieving these depths of color, and permanence. Curator: Considering that labor and the artistic process—stained glass windows had previously been for ecclesiastical spaces. How does displaying an elite sitter like this young man complicate power dynamics in Dutch society? It represents not just individual power but the social power of that type of representation. Editor: It does challenge pre-existing religious narratives. Moreover, understanding its materiality, what survives to this day, highlights an economic story. Consumption and value intersect; this piece, like stained glass, it resists the total annihilation that may have effected other, similarly scaled, works during conflicts of that period. Curator: These insights, considering both the sitter and artistic process, allow a fuller appreciation. Glass from the 16th century acts as both record and reinterpretation. Editor: The interplay of material endurance and historical interpretation helps us engage the legacy, how artworks are used, displayed, and affect different audiences across time and context. It’s all intertwined.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.