Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

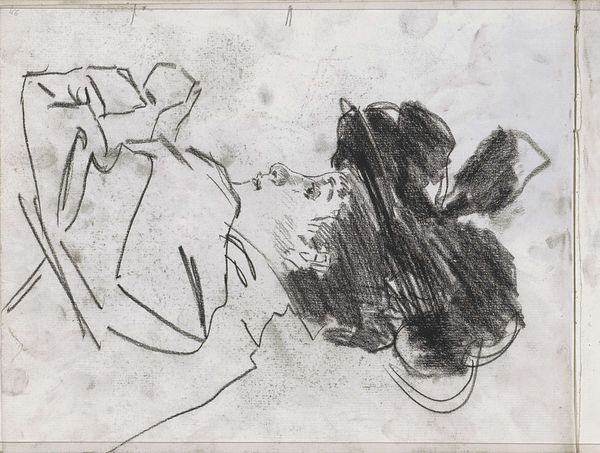

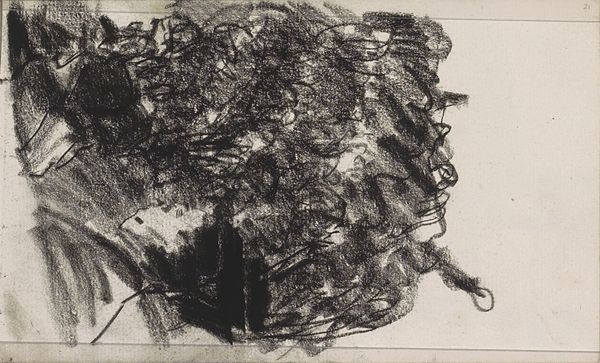

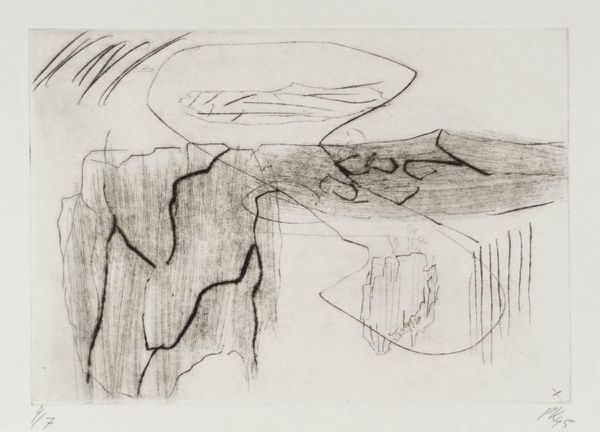

Curator: I'm struck by the stark contrast in Isaac Israels' "Woman, Possibly on a Balcony." The dramatic chiaroscuro and gestural marks imbue this portrait with an arresting quality. Editor: It's undeniably somber. There's an immediacy in the rawness of the lines, the unresolved forms. The subject feels almost shrouded. Is it pencil, charcoal, or both? Curator: Likely a combination, done between 1887 and 1934, judging by the free application, which reveals his impressionistic tendencies—it's currently at the Rijksmuseum. The tonal gradations capture a world of emotions beneath the surface, from pensive to mournful. It is like a spirit lurking at the edge of perception. Editor: True. And the strategic use of line seems deliberately ambiguous, blurring figure and background. It flattens the space while still suggesting a figure occupying it. Note the way Israels defines form less by contour and more by the directionality of his strokes. There’s almost a structuralist game at play. Curator: But even through the visual ambiguities, a palpable presence emerges. The balcony setting—suggested, but not fully articulated—hints at themes of confinement and freedom. Perhaps she’s contemplating a choice or longing for something beyond her reach. She is a sibyl watching something unfold below her. Editor: The visual tensions between presence and absence really reinforce this feeling. There is an inherent incompleteness of the representation—and of the subject as well, perhaps. The rough application makes it difficult to ascertain precisely who we see; however, she remains deeply recognizable nonetheless. Curator: We have to recall the context of that era—portraits served to codify status, memorialize lives, and also often conceal painful psychological truths. To me, that smudging, those indefinite lines, suggest all that unspoken grief, disappointment and unrealized hopes of many women's lives in this epoch. Editor: So well put. By visually breaking down the coherent form, Israels' drawing invites contemplation of more than just appearance, it really compels you to examine the nuances that underpin visible reality. Curator: Yes, by deconstructing a face, a figure in charcoal, it also opens doors into hidden emotional landscapes, into worlds of feeling. Editor: Indeed, in this portrait by Israels, form is ultimately the genesis of something more: feeling itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.