drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

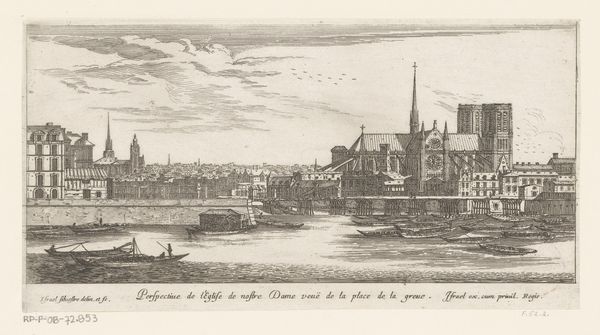

Editor: So, here we have Israel Silvestre’s “Veue de l’Eglise Nostre Dame de Rouen,” made in 1664. It’s a cityscape created using etching and engraving. What strikes me is how bustling it is, full of boats and people, yet dominated by the imposing architecture of the cathedral. What catches your eye about it? Curator: It's interesting to see Rouen portrayed like this. Silvestre's view highlights not just the religious power represented by Notre Dame, but also the city's economic life, doesn't it? How the church literally looms over the commerce happening on the river… a clever juxtaposition. What do you make of the artist’s decision to include so many figures? Editor: I think it makes the scene feel more dynamic and relatable. It’s not just a monument; it's a place where people live and work. But is he perhaps glorifying something with these elements? Curator: Perhaps. Prints like this served multiple purposes. On one hand, they provided records of architecture and cityscapes and allowed the wider dissemination of certain places. On the other, they are always underpinned by ideological viewpoints: the promotion of civic pride or specific social structures through carefully chosen viewpoints. Who are the figures, and how are they represented? Those boats crossing are not only functional transport, they may well highlight specific activities. Editor: That makes me see this piece in a different light! I hadn’t considered how consciously constructed the image must be to convey a particular message about Rouen's status. Curator: Precisely! And thinking about Silvestre himself, how might his position as a printmaker shape his presentation of the city? Editor: Well, I guess as a printmaker, the more prints sold the more money you made, so he probably highlighted the appealing, successful elements of city life. I hadn’t thought of it that way before. Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.