print, daguerreotype, photography, albumen-print

#

16_19th-century

# print

#

war

#

landscape

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

19th century

#

men

#

united-states

#

history-painting

#

albumen-print

#

realism

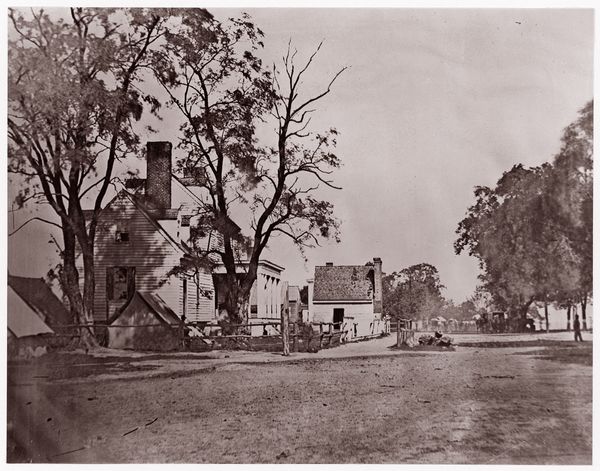

Dimensions: 17.7 × 22.5 cm (image/paper); 31.1 × 44.7 cm (album page)

Copyright: Public Domain

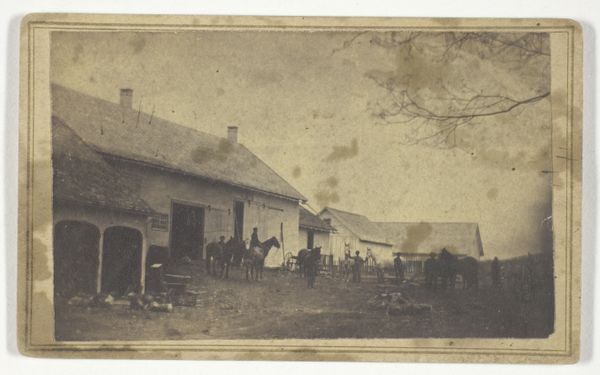

Curator: This albumen print, dating back to 1862, captures a moment in Centreville, Virginia, during the Civil War. The photograph, titled "Stone Church, Centreville, Virginia" is credited to Barnard & Gibson, or rather, the negative is. The print itself was made from that negative, bearing A. Gardner's imprint. Editor: It evokes a stark emptiness, even with the figures present. The grey scale contributes, giving it a removed and desolate feel. There's also something deeply unsettling about how mundane it all seems. Curator: Mundane, perhaps, but photographs like these served a powerful purpose. Think of Matthew Brady’s studio, or Gardner’s; they sought to document the war with stark realism, shaping public opinion by presenting an unvarnished view of the conflict. We're looking at more than just a landscape; it's an attempt at historical record. Editor: And a record heavily curated, nonetheless. The framing, the composition – everything speaks to the control exerted over the narrative being presented. Note the presence of the Union soldiers; they're arranged almost formally, lending a visual endorsement to their cause within the setting. How does that impact perceptions of neutrality in photography? Curator: Indeed. Consider the image's potential audience, largely the Northern public. These carefully composed scenes could galvanize support by demonstrating Union presence, control, and perhaps, a sense of inevitable victory even amongst a brutal civil war that tore apart the US landscape and political spectrum. The church becomes a symbol, almost, of enduring American values in the face of adversity. Editor: Or a symbol of imposed values. Given that war is fought on ideological grounds, that imposition raises ethical questions about how "history" is visualized, then circulated and digested, isn't it? Who gets to frame the story, and at whose expense? The power dynamics inherent in photography itself become magnified during wartime. Even what isn't pictured becomes significant. Where are the freed people? The enslaved? The dissenting voices? Curator: A crucial consideration. The absences are often as telling as the presences. We might also analyze the impact on Centreville itself, as a captured landscape within the ongoing conflict; or rather how photographers and publishers captured Centreville in its specific condition in 1862 and how such visual tropes are then consumed within the socio-political realm in the US, then, but also now. Editor: It makes you ponder the unseen ramifications. This single image then opens up a web of socio-political interrogation on its impact. Curator: Precisely. By considering both the image’s context and the forces shaping its creation, we gain deeper insight into the history it attempts to capture. Editor: Ultimately, viewing artwork like this is never passive. It is up to the viewer to unravel meaning within the art in its historical framework and intersectional space, while simultaneously reflecting on the sociopolitical messages, intentions, and historical impact the artwork communicates.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.