painting, oil-paint

#

cubism

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

geometric

#

abstraction

#

cityscape

#

modernism

Copyright: Public domain US

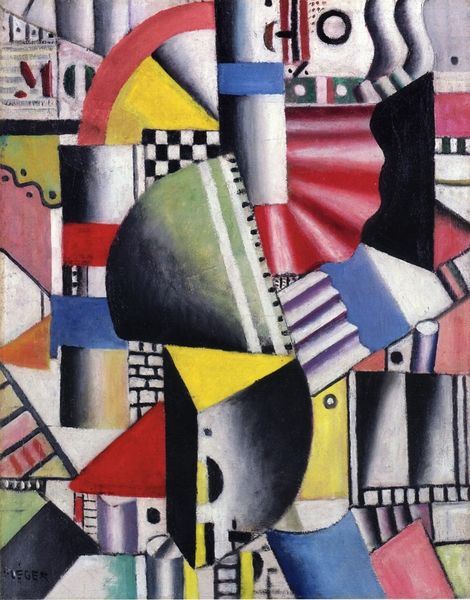

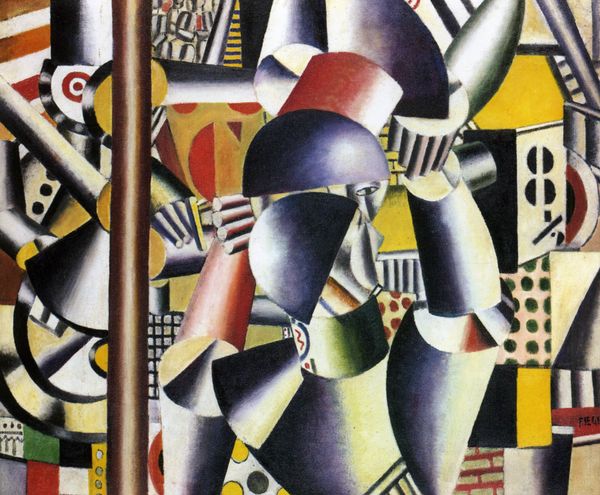

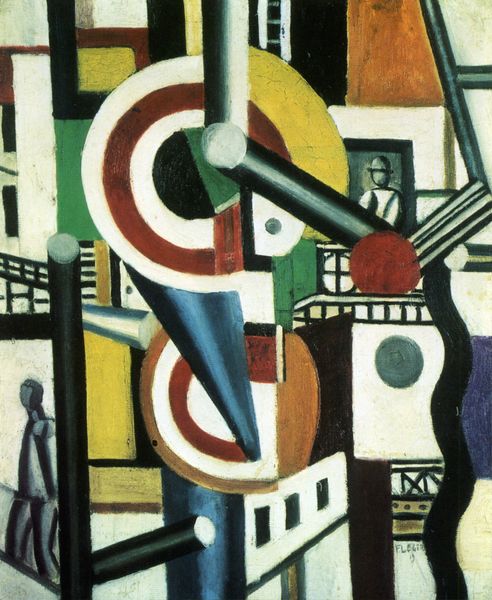

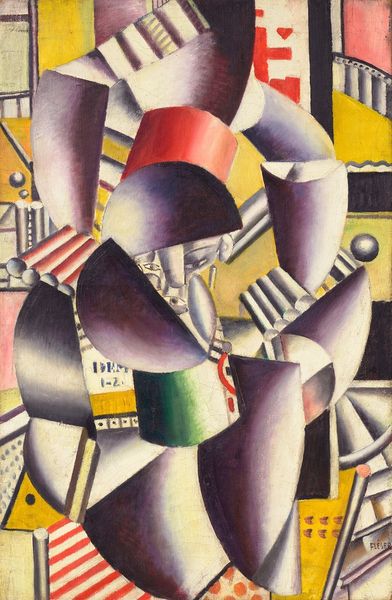

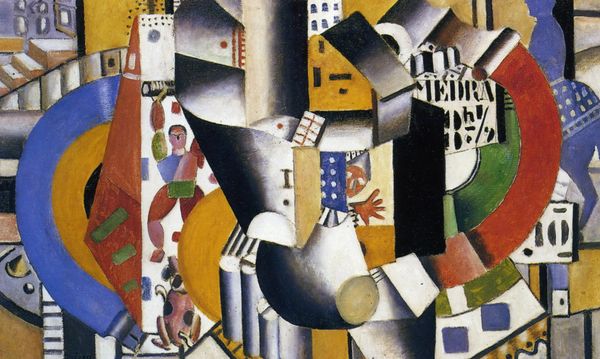

Curator: Fernand Léger’s “The Stove,” painted in 1918, is an explosion of color and geometric form. What’s your initial read on this work? Editor: Disorienting, immediately. A bombardment of shapes. But strangely, there's a tactile quality here, a sense of implied textures and implied movement in an industrialized context. Curator: Léger was deeply engaged with the modern industrial world. Semiotics would suggest that the geometric forms aren’t random but are stylized depictions of machines and architecture. The overlapping planes create a dynamic tension, reflecting the dynamism of urban life. Editor: And painted so shortly after the devastation of World War One, how might Léger be reconciling machine-made objects, now associated with mass slaughter, with the recovery of a war-torn society? Were such paintings optimistic in tone, a look to the future, or warnings about humankind’s reliance on destructive war machines? Curator: An astute observation. Léger’s post-war work explores that ambivalence. In “The Stove,” the stove might symbolize domesticity, but its sharp lines, combined with industrial motifs, question the traditional dichotomy of home and factory. We can look closely at how his style employs both angular and curving shapes for balance, which he called " contrasts of forms.” Editor: The contrasting black and white elements arranged close to brightly-colored geometric planes feel jarring. Léger is playing with binaries. The checkerboard near softer lines seem as though traditional, familiar motifs can sit—somewhat uncomfortably— alongside the chaos of modern mechanized forms. Curator: The painting also challenges the conventional use of perspective, thus creating a unique viewing experience, an invitation to embrace ambiguity. Léger himself explained that one should “see the object, not its reproduction.” Editor: Considering the politics and rapid social change happening across Europe at the time, it makes sense he may be suggesting, through this work, to focus less on strict representationalism and, instead, embrace progress—though tentatively. Curator: So we might view the artwork through the lens of the socio-political issues that permeate, using them to consider and reflect upon art in modernity. Editor: Exactly, to move past just analyzing how something is shown, to interrogate what is actually being said.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.