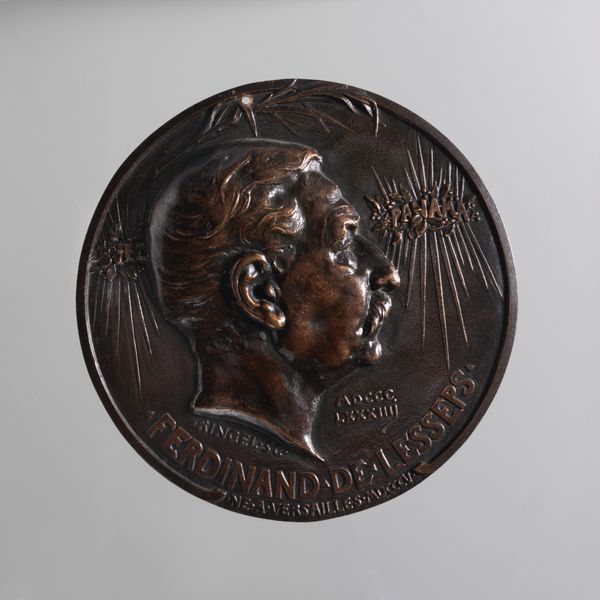

metal, relief, bronze, sculpture

#

portrait

#

metal

#

sculpture

#

relief

#

bronze

#

11_renaissance

#

sculpture

#

italian-renaissance

#

early-renaissance

#

statue

Dimensions: overall (irregular oval): 20.1 x 13.55 cm (7 15/16 x 5 5/16 in.) gross weight: 1646.5 gr (3.63 lb.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: What strikes me immediately is the profile’s reserved gaze. It feels almost Roman in its stoicism. Editor: Well, this bronze relief, dating from around 1435, is a self-portrait of Leon Battista Alberti, an important figure of the Italian Renaissance. Its ovoid shape and material give it a uniquely portable presence, doesn’t it? Curator: Yes, portability meant visibility in that era! This bronze medium connects him to traditions of power and intellectual authority—sculpture has been tied to remembrance since ancient times. Notice, also, the placement of the eye; looking outward, like classical statues of emperors. Editor: I’m struck by how shallow the relief is, actually. The form barely emerges from the background. It almost feels like a coin, further reinforcing this idea of circulation and recognition. And consider Alberti’s gaze in tandem with his signature—it creates an immediate visual grammar with few formal interruptions. Curator: Absolutely. And there’s a tension between his detailed facial features—that slightly furrowed brow—and the more symbolic imagery beneath. I mean, what do we make of that winged eye there, nestled under his draped shoulder? That imagery of watchfulness speaks to deeper ideas about knowledge. Editor: Semiotically speaking, it introduces a third term into the binary portrait. The profile/signature divide expands, layering further meanings. In early Renaissance art, the emblem and the portrait served distinct rhetorical purposes. The artist unites these functions here. Curator: Right, that winged eye is doing heavy lifting here in symbolizing not just seeing, but understanding. It resonates with concepts of providence and human intellect blooming in that moment. Alberti isn’t just showing himself; he’s telegraphing a humanist worldview. Editor: Indeed. To look at it structurally, that motif destabilizes the composition, making us think about it critically as a synthesis of text and image, not simply a mimetic likeness. The visual texture pushes beyond basic identification. Curator: It all points towards Alberti’s conscious cultivation of an image. He’s controlling not just how he’s seen but how his intellect is understood and passed down. This becomes an iconic object precisely because he made symbolic considerations with visual skill. Editor: A fascinating combination, that. Alberti provides future viewers like ourselves with an almost programmatic viewing experience that nonetheless still surprises. Curator: I agree entirely. This image becomes an early document of our desire to find meaning behind an individual identity during a pivotal moment.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.