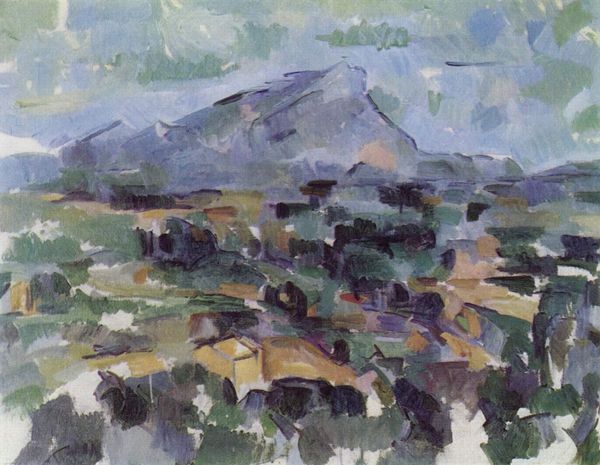

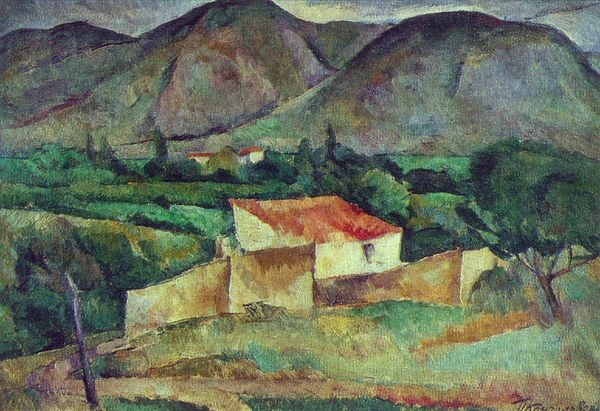

oil-paint, montage

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

oil painting

#

montage

#

post-impressionism

Dimensions: 55 x 65 cm

Copyright: Public domain

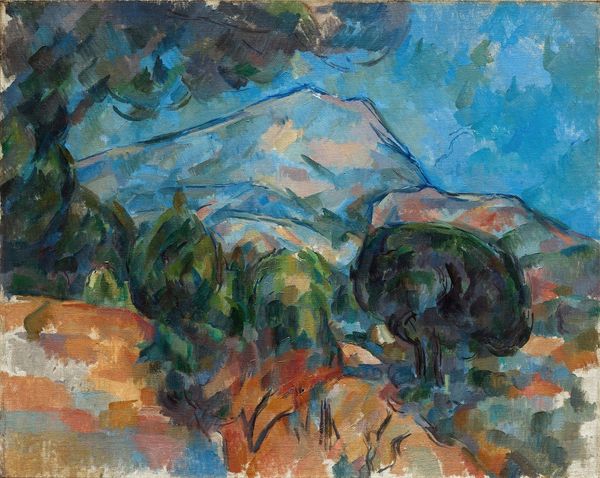

Curator: Welcome! Today, we’re looking at Paul Cézanne's "Mont Sainte-Victoire," an oil on canvas created around 1890. It’s currently housed here at the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh. Editor: Well, looking at it, I’m immediately struck by the somewhat crude layering of paint. It feels almost unfinished, like we’re witnessing the bare bones of the landscape itself. Curator: Absolutely. It's a far cry from traditional landscapes which is partially why it’s considered to be such a watershed moment for what paintings can express. Instead of an illusion of depth, he’s prioritizing flatness and structure. What Cézanne ultimately achieves is a deconstruction of the established conventions of landscape art, leading the way to the development of more radically representational practices by younger painters such as Braque and Picasso. Editor: I see that... the more I look, the more I’m aware of the materials themselves – the thick brushstrokes, the canvas, the weight of the pigment. It's as though he wants you to consider the very act of painting, its labor and tangible presence. What would he use? What does this process signify about his work, beyond just depicting pretty landscapes? Curator: The emphasis on materials and method definitely challenges the romantic idealism tied to traditional landscape paintings, pushing instead for an interrogation of visuality itself. The mountain wasn't simply picturesque subject matter. Editor: But also a question: what does labor on the landscape mean? Here we see his active process, both his intellectual labour as well as physically putting paint to canvas in such thick heavy-handed gestures. I suppose Cézanne aimed to engage our sense of sight with every aspect of painting. Curator: It also challenges the prevailing view of artists as detached geniuses, and really emphasizes the value and hard-work it takes to challenge conventions. I think what strikes me most, ultimately, is the work's impact on artistic vision; and the influence such work has on movements such as Fauvism or early Cubism. Editor: Yes! So, for me, Cézanne invites a tangible appreciation for how something like this gets produced and what processes were involved. The painting, its very ‘thingness,’ almost becomes the message. Curator: A testament to challenging the art world, one landscape at a time. Editor: Quite the revolutionary gesture of landscapes as objects, indeed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.