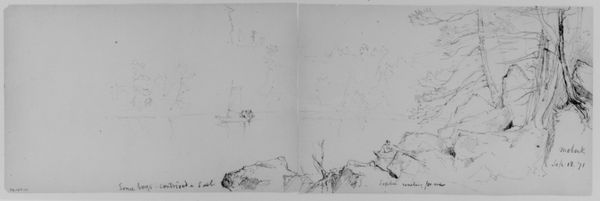

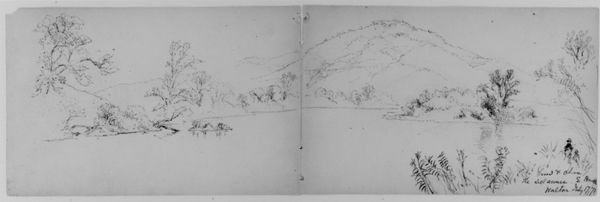

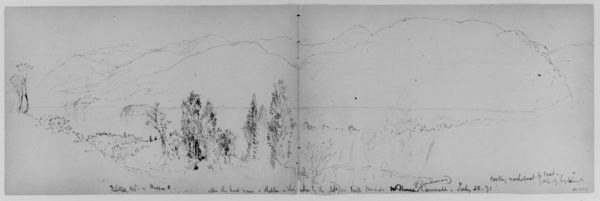

Dimensions: 5 1/2 x 8 3/4 in. (14 x 22.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

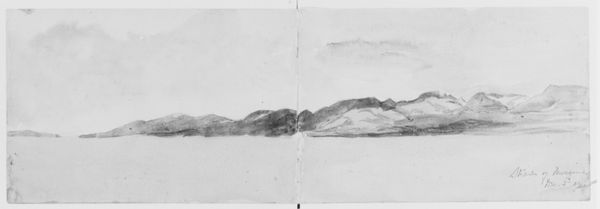

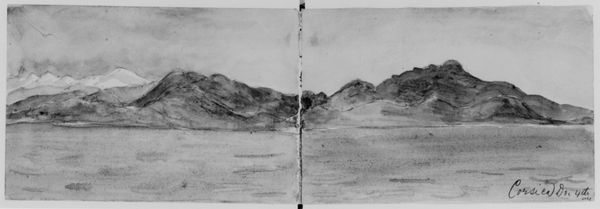

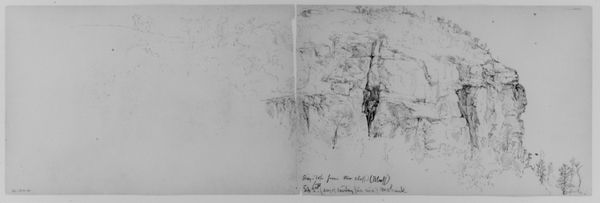

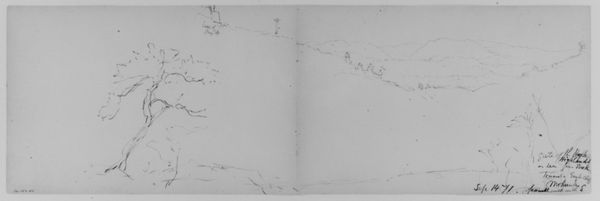

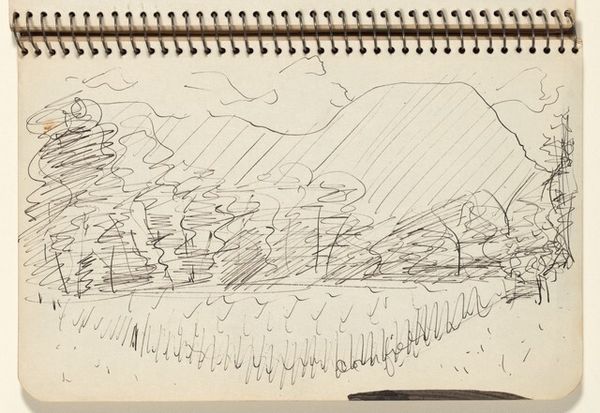

Curator: Looking at Daniel Huntington's "Cornwall, 1871" sketch, found within a sketchbook dating from 1870, my initial impression is how quietly atmospheric it is. The softness of the ink makes me feel like I'm seeing it through a veil of mist. Editor: It's intriguing that you say quiet, as the very act of plein-air sketching in the 19th century could be seen as a form of social engagement. Huntington, a prominent figure at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Century Association, likely understood his artistic endeavors as part of a larger public discourse. The sketchbook becomes a mobile platform for observation, later destined for presentation. Curator: True, and there's an immediacy in the lines themselves, so observational! You can almost feel him trying to capture the light dancing on the water, even in its incompleteness. It makes me think of first impressions; fleeting feelings put to paper before they can truly form. It's so raw. Editor: And that raw quality reflects shifting notions of artistic training. Artists were increasingly encouraged to develop direct responses to nature, seen as authentic experience outside academic stricture. So what feels like an intimate, personal moment is actually Huntington positioning himself within this Romantic ideal. We should also mention the historical value. Sketchbooks offer insights into artists' processes rarely revealed by finished paintings, a candid view into their creative routines and how the sausage is made, so to speak. Curator: You’re right, it’s a great point—we only get to see these under-the-hood views every so often! Looking closer, I notice how he's used the full double-page spread. Do you think that reflects a conscious desire to create a sense of vastness? He has left a signature too—there’s a strange intentionality here that is in stark contrast to other, purely observational studies. Editor: Possibly. And the signature hints at something to your point about the incompleteness too. Although rendered in ink on paper, the “Cornwall, 1871” landscape has a clear position within a broader cultural context for displaying romantic scenes of pastoral lands. While we read the sketchy elements as pure landscape, there may well be a dialogue here about framing these more directly personal observational experiences. Curator: Looking at the Met’s placement of the drawing, it brings these historical layers to the foreground, especially as a “study”, which highlights its making-of potential. Thanks for reframing what I initially saw as intimate and ephemeral, by bringing to light how culture impacts viewing in and of itself! Editor: Absolutely, seeing these details through your interpretation helps to remind us that sketching traditions create frameworks of knowledge as much as pure artistry!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.