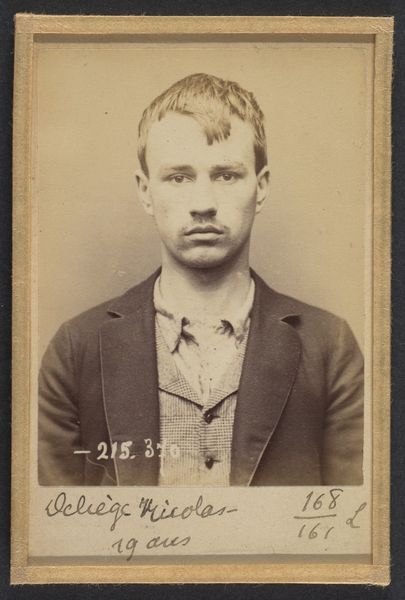

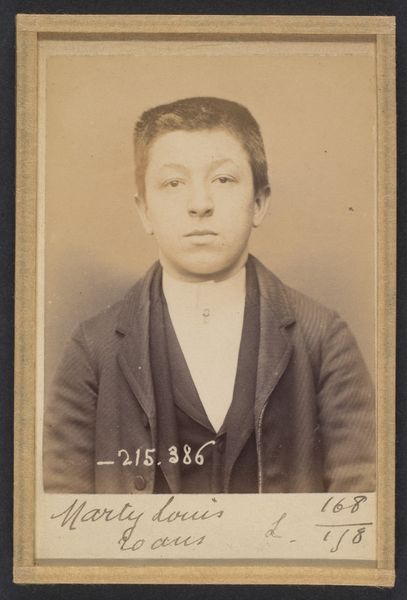

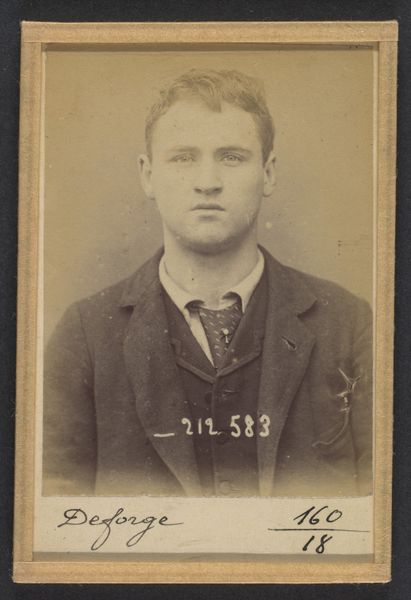

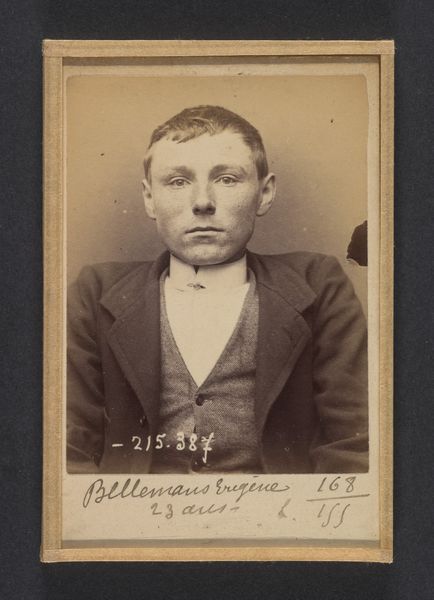

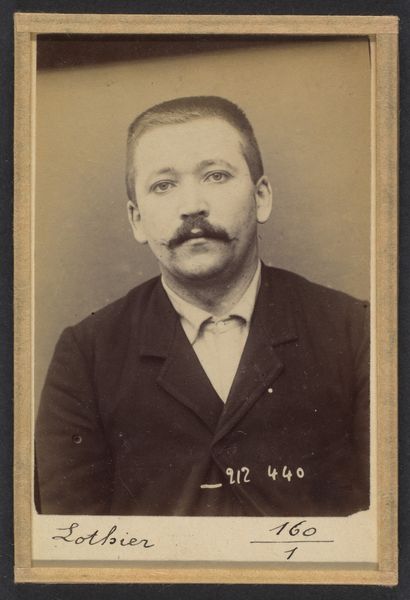

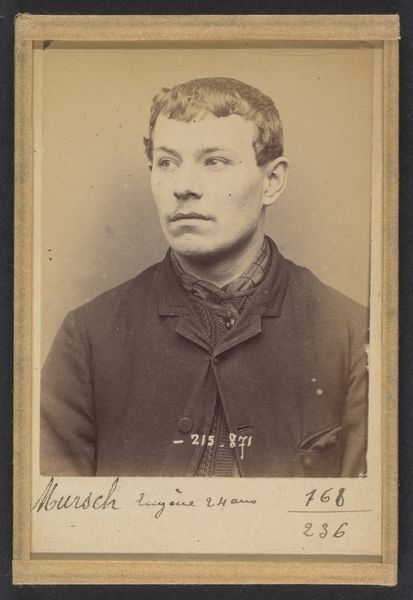

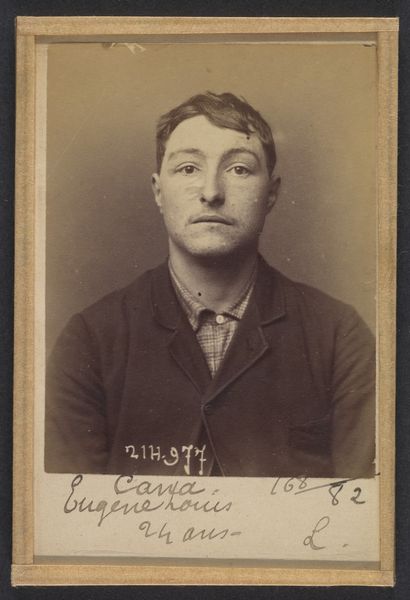

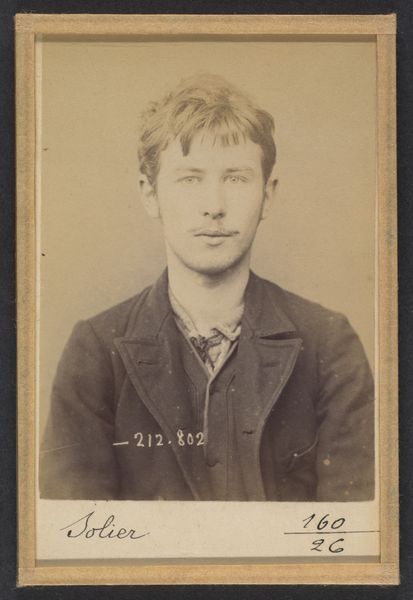

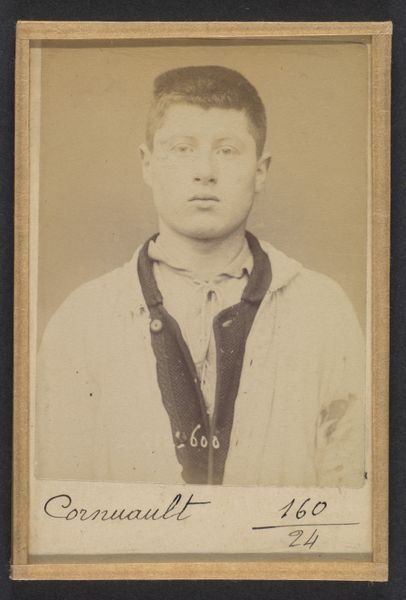

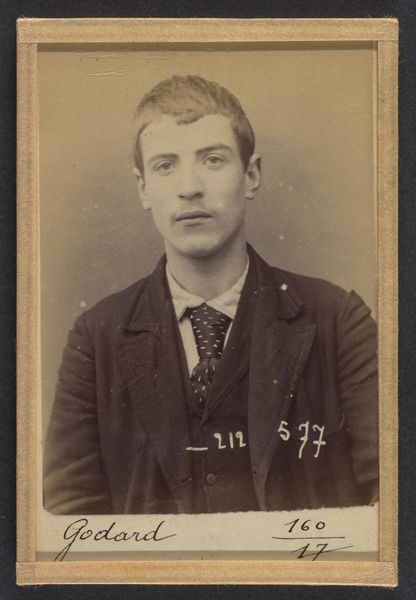

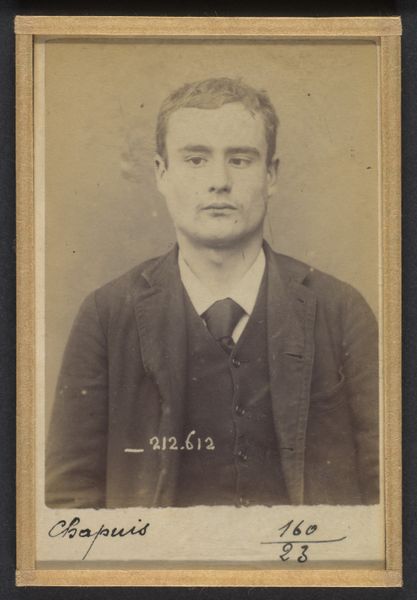

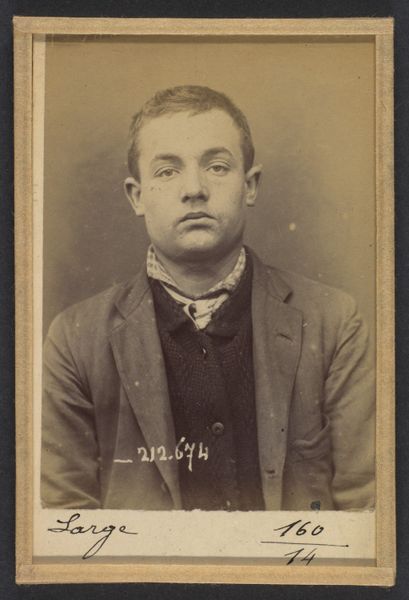

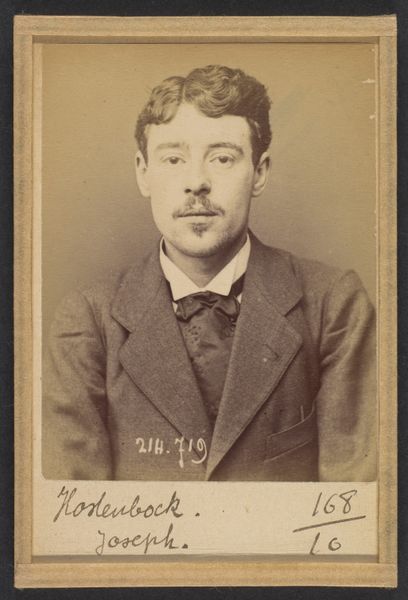

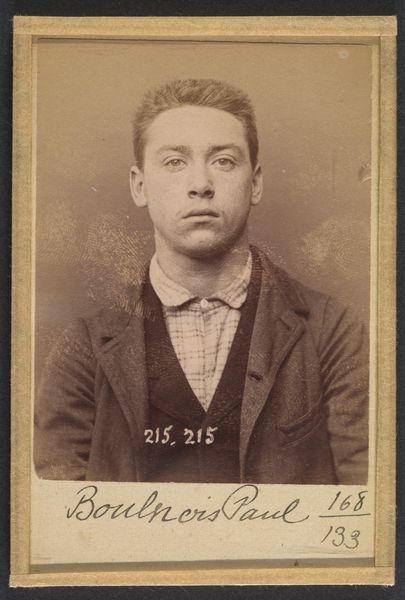

Bordes. Auguste. 15 ans, né à Paris XVIIIe. Garçon Marchand de vins. Anarchiste. 9/3/94. 1894

0:00

0:00

print, daguerreotype, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

african-art

#

portrait

# print

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

history-painting

#

modernism

#

miniature

#

poster

Dimensions: 10.5 x 7 x 0.5 cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.) each

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: We’re looking at a gelatin silver print by Alphonse Bertillon, titled "Bordes. Auguste. 15 ans, né à Paris XVIIIe. Garçon Marchand de vins. Anarchiste. 9/3/94.", dated 1894. There's a haunting quality to this image, it's quite stark and sobering. What can you tell me about why it was made? Curator: This is an early example of forensic photography. Bertillon was a French police officer and biometrics researcher, who pioneered the “Bertillonage” system. It's interesting to see how scientific and political needs shaped the use of photographic portraiture in the late 19th century. Consider it: before widespread photography, how did authorities track criminals? Editor: So it’s less about art, and more about… policing? This feels really different from traditional portraiture. Curator: Precisely. Though, the aesthetics adopted borrow from then popular portrait photography styles, it departs radically in intention and its socio-political context. We see the subject posed formally, yet labelled and categorized. Does the text below, naming his affiliation, influence how you view his face? How does this compare to, say, a Nadar portrait? Editor: Definitely. Knowing he was labelled an anarchist...it's hard *not* to see it in his expression, even though that's probably just my bias! The power dynamics at play are pretty disturbing. It makes me question the objectivity of the image itself. Curator: That’s the key question. Photography was quickly adopted as an objective medium, but images are never truly neutral. They reflect the intentions and biases of those who create and use them, and in this case, also carry societal judgement. How this ‘neutrality’ becomes associated with ‘truth’ is an important issue to confront. Editor: This makes me rethink photography's role in shaping historical narratives and reinforces the value of critical analysis. Thanks! Curator: A good image asks more questions than it answers, doesn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.