drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

figuration

#

realism

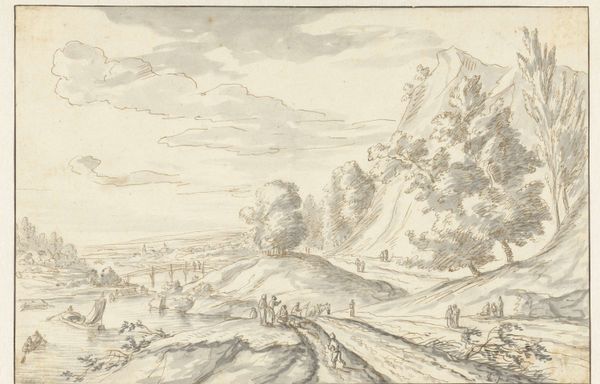

Dimensions: sheet: 8 7/16 x 10 13/16 in. (21.5 x 27.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Up next, we have Herman Saftleven II's "Fantasy Rhine Landscape," created around 1650. What’s your first impression? Editor: It's lovely, subdued. The whole piece feels veiled in a kind of soft, almost melancholic light. It reminds me of late afternoon, watching the sun sink behind a hill and create subtle gradations of light across the scene. Curator: Indeed, there is a tonal quality to the etching, but consider how Saftleven achieves this affect using hatching. He's not only giving us this placid scene but also meticulously building layers. What strikes me most is how printmaking in the 17th century allowed artists to democratize images of their world—creating them with tangible work through manual labor that made them relatively more affordable and available to the public. Editor: Absolutely, printmaking serves as an accessible tool and offers insight into the culture it was produced in. Here you have what seems to be tradesmen and wanderers on this little bluff; you see their goods beside them on the hill overlooking the Rhineland, it seems almost performative to sit up there while their living sits at bay down below. It makes me consider our relation to capital now, and whether we, too, fetishize production, creating separation from labor for the sake of status and optics. Curator: I wonder how many impressions Saftleven would pull from his copper plates? How consistent the final prints? Thinking about his physical endurance, in combination with access to materials. There were no inkjet printers back then! But also, it prompts questions about originality and replication—what is gained and lost when an image moves from being unique to existing in multiple copies? Editor: It is as much about availability and access as it is endurance. Think of the material quality! He worked, physically and psychologically, with such discipline on a drawing to prepare for an image he wouldn't see quite the same once printed, that's kind of wild, to labor toward an image, to prepare, and prepare, and still relinquish that control to an etching press? Curator: It does change everything. As someone encountering the work almost four centuries later, I like thinking about that labor, not just the end result. Editor: Me too. To make beauty, and make beauty accessible!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.