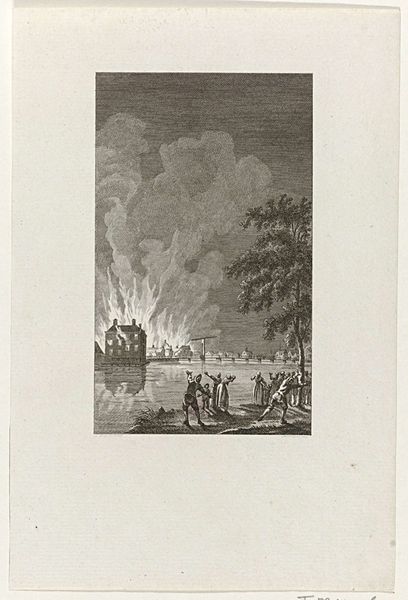

Dimensions: height 179 mm, width 111 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

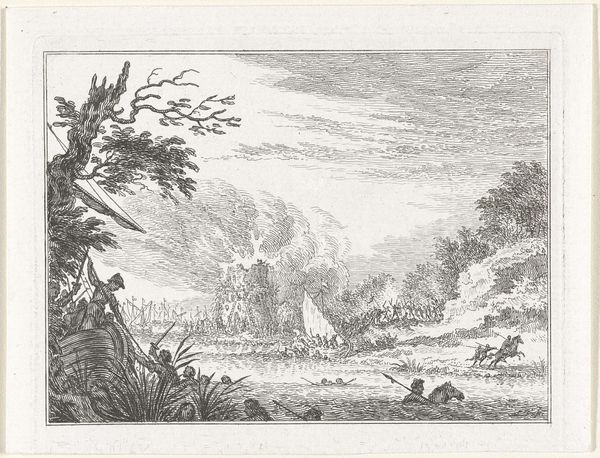

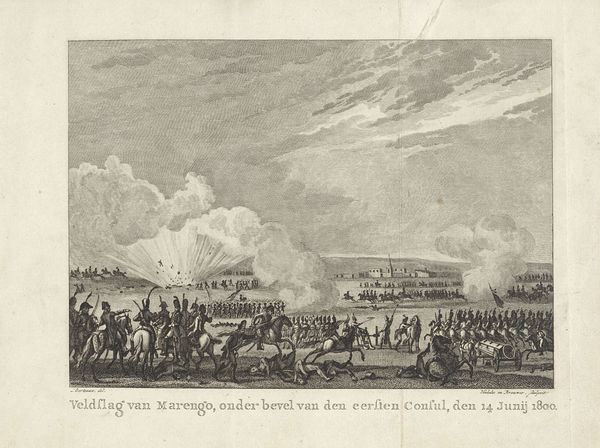

Editor: Here we have Reinier Vinkeles' engraving, "Vuurgevecht bij Vreeswijk, 1787", from 1793, housed here at the Rijksmuseum. It's rendered in stark monochrome, and it’s... intense. I'm immediately drawn to the puffs of smoke and figures frozen in action, but I wonder what this specific clash signifies? How do you interpret this work, particularly in light of its historical context? Curator: Well, this print serves as a powerful piece of political imagery. It’s not just about a battle; it's about how the Dutch viewed this period of upheaval and conflict. Remember, it was made in 1793, several years after the event itself. Vinkeles, and those who commissioned this, had an agenda. Look at how the composition frames the conflict – what side seems to be emphasized or glorified here? Editor: I notice a clear division between the two groups of figures, with one side much larger and more detailed, whereas the other seems to almost be a mass. It feels like the print encourages the viewer to relate to the side more visibly characterized, especially given that they're closer to us in the foreground. Is that reading too much into it? Curator: Not at all. Consider that the “patriots” or revolutionaries had seized control of cities like Utrecht, which then triggered intervention by the Prince of Orange to reinstate the old order. By creating this print, Vinkeles participated in the public discourse and tried to sway public opinion. How might prints like these have influenced political sentiments at the time, reaching even those unable to read, given that it visually captured events that not many had the privilege to witness first-hand? Editor: So, it's like propaganda in a way? Visual media shaping a specific political narrative. Curator: Precisely! Think about the role of museums like the Rijksmuseum in displaying such works today. How do they present this piece, and what narratives do *they* perpetuate or challenge through its presentation and interpretation? It definitely provides us a window into 18th-century political struggles and the politics of visual representation itself. Editor: This engraving has made me rethink how seemingly objective depictions of history can be laced with bias and how museums contextualize their holdings. Curator: Indeed. History is not just about what happened but also about who tells the story and why. And art often serves as one of the most compelling storytellers.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.