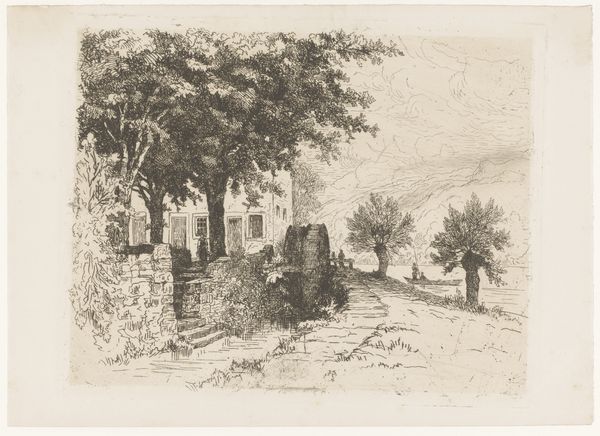

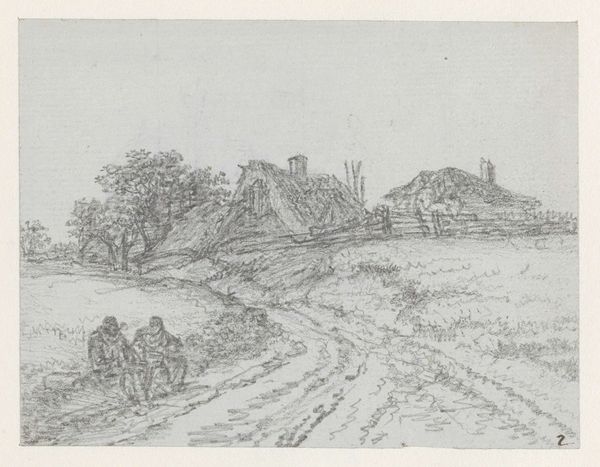

Dimensions: height 123 mm, width 196 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: At first glance, I see delicate chaos. It’s almost all lines, like whispers on old parchment, but somehow solid, too. Editor: You've hit upon a crucial tension within Willem Matthias Jan van Dielen’s work, "Landschap met ruïne en twee figuren" – "Landscape with Ruin and Two Figures". Produced in 1859 using etching, the artwork exemplifies how romanticism grapples with ruin, history, and nature's encroachment upon human endeavors. Curator: The ruin really dominates, doesn't it? It's right there, practically dissolving into the foliage, but holding its ground too. Gives me this wistful, seen-better-days sort of feeling, like time is swallowing stories whole. Editor: Exactly. Van Dielen was operating within a Romantic tradition where ruins signified the transience of human achievement, allowing for contemplation on the cyclical nature of history and the power of the natural world. The ruin as a visual trope was heavily laden with meaning for contemporary viewers. Curator: And there are the two figures on the left there! They’re tiny in comparison, almost swallowed up by the land. Perhaps emphasizing our fleeting moment in grand sweep of time. Or perhaps I’m being too dramatic. Editor: Not at all. These diminutive figures serve a vital purpose. Functionally, they provide scale, underscoring the immensity of the ruin and, symbolically, drawing us into a dialogue with mortality and human presence against a backdrop of historical decline. Van Dielen, and his contemporaries, are inviting viewers into a carefully constructed melancholic conversation. Curator: So, a romanticized doom and gloom, but beautiful, and delicately executed, not overwhelmingly morose! All those detailed lines… it feels like searching for something. Editor: In some ways, Romanticism reveled in beautifully rendered melancholy. Van Dielen has not just represented a ruin; he has built a visual poem about the intersection of history, nature, and our place within it. The fact that this is an etching makes it even more interesting, as it speaks to accessibility and distribution of imagery to the broader public. Curator: Looking again, it definitely encourages one to lean into the quiet side of reflection. Perhaps even find a bit of solace there, amidst the ruin. Editor: I find myself contemplating the conversations such imagery might have spurred within burgeoning art markets and institutions—all attempting to reconcile and reflect Holland’s self-image in the wake of immense social transformation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.