Utrechtse maskerade van 1851: Unie van Utrecht in 1579 1851

0:00

0:00

antoniejohannesgroeneveldt

Rijksmuseum

drawing, ink, pen

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

pen sketch

#

figuration

#

ink

#

pen

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 477 mm, width 620 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

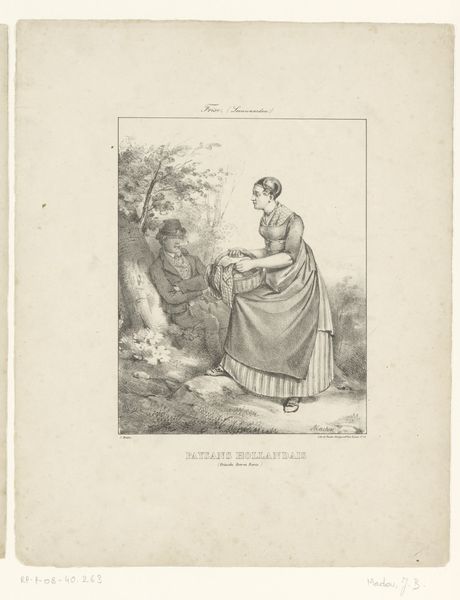

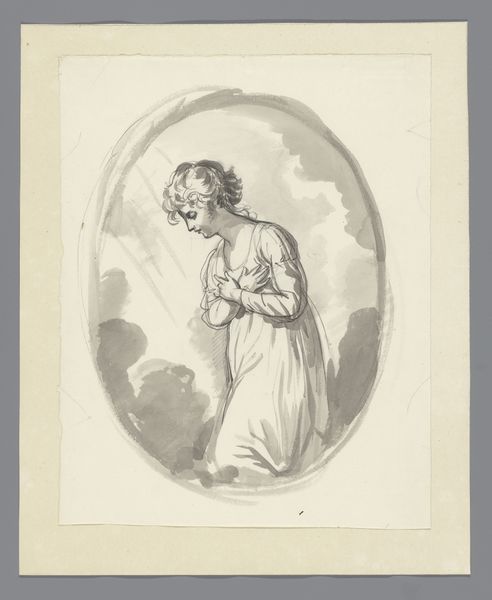

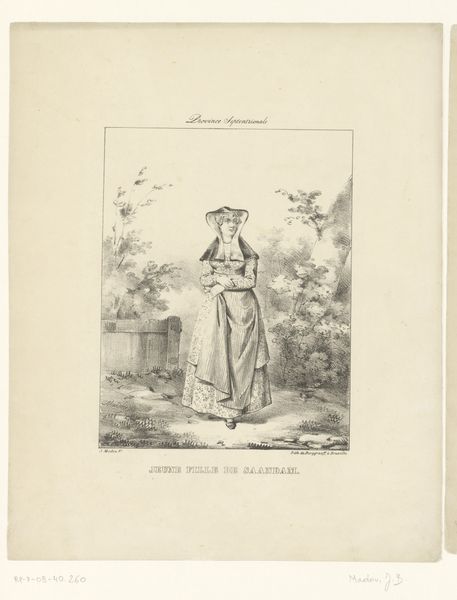

Editor: This pen and ink drawing, "Utrechtse maskerade van 1851: Unie van Utrecht in 1579" by Antonie Johannes Groeneveldt, is housed in the Rijksmuseum and dates to 1851. The woman looks like she’s posing for a photograph, and there is a scribbly backdrop like she is sitting outside. I’m immediately curious about this woman: how should we interpret her in the context of this artwork’s name? Curator: This piece seems to be engaging with ideas of Dutch identity and nationalism, which were obviously very fraught subjects in the mid-19th century after the Napoleonic era. The “Union of Utrecht” refers back to a key moment of resistance, and this “maskerade”, or masquerade, signals something performative and not quite genuine is happening. What strikes you as a modern viewer? Editor: Well, the theatrical element. Is she meant to embody some abstract concept related to the Union, perhaps? Also the way that some parts of her are drawn with strong strokes while other areas blend into shadow makes her the central element of this work. The text, which may or may not be original to the artwork, mentions "Tweede Kamer." Was it originally published, or maybe intended as a political cartoon? Curator: Exactly! It appears to have been part of a broader commentary on the political theater of the time, gesturing toward questions about who truly represents "the nation" and what historical narratives get prioritized. Think about whose stories are validated within nationalist rhetoric, and whose are conveniently erased or omitted. Do you see visual elements that convey how these power imbalances may be at play? Editor: I think you are right that it’s impossible to detach this work from its historical and social context and the impact it has even on today’s socio-political relations, given the allusions to the Union. And, to me, it has shifted from a mere sketch of a woman to a more meaningful object and embodiment of 19th-century Dutch identity. Curator: Indeed. It’s a reminder that seemingly simple portraits or genre scenes can often be sites of intense negotiation over national identity, gender roles, and the construction of historical memory. I hope that we have both learned how it calls into question not only what is visible, but also what's been historically and socially masked.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.