#

constructivism

#

form

#

geometric pattern

#

geometric

#

geometric-abstraction

#

abstraction

#

line

#

geometric form

#

modernism

Copyright: Josef Albers,Fair Use

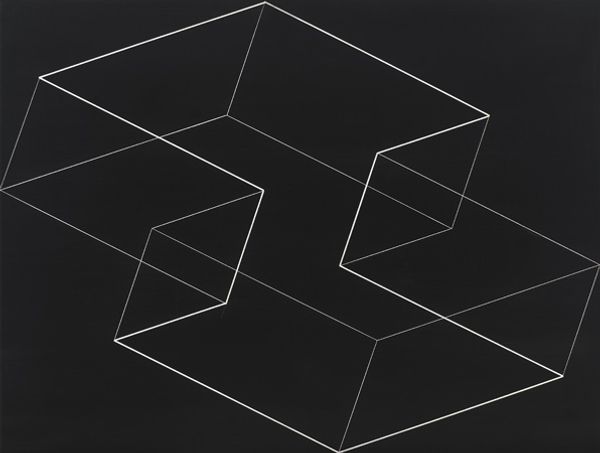

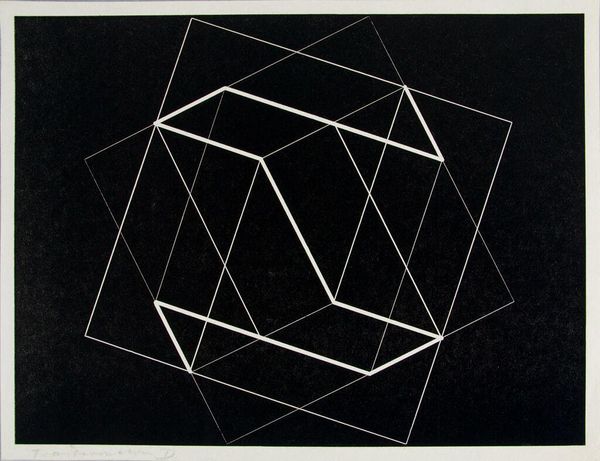

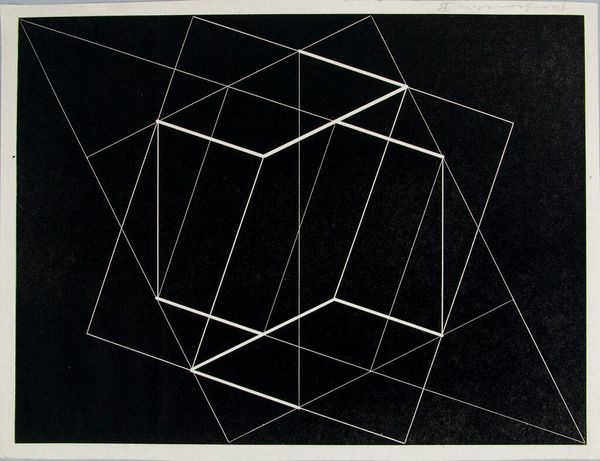

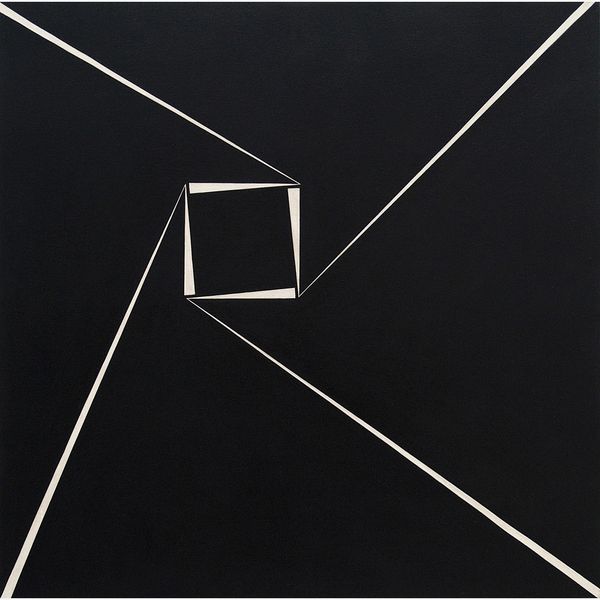

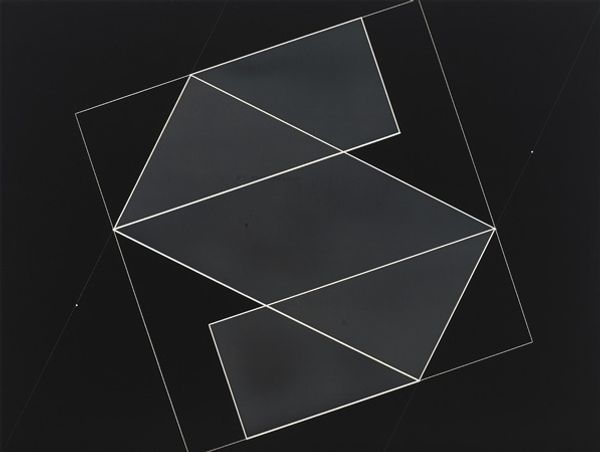

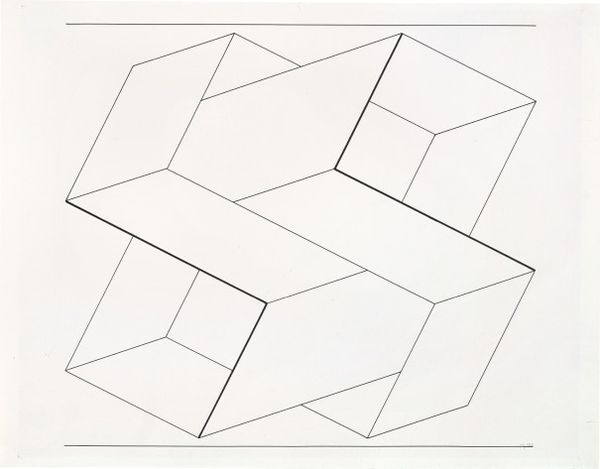

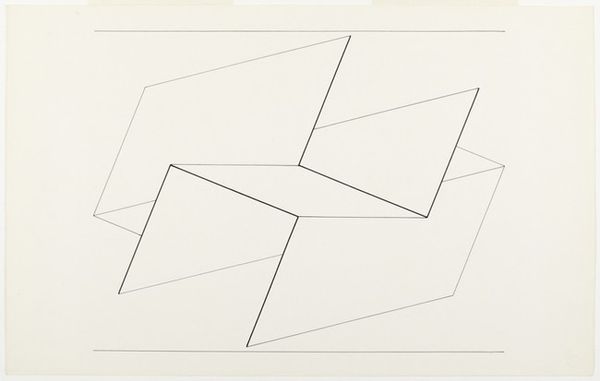

Curator: Welcome. Here we have Josef Albers's "Twisted but Straight," created in 1948. Albers, of course, fled Nazi Germany and began teaching in the United States. Art Historian: My first impression? It's austere, yet playful. It gives the illusion of depth but remains stubbornly flat. Curator: I find that tension fascinating. The piece engages with the political landscape of the time, albeit abstractly. Post-war anxieties around perceived deception were definitely around. Here we have forms which appear familiar, stable even, like cubes, yet are just beyond our ability to resolve them, decentering the viewer's perception of reality. Art Historian: I’m struck by how universal geometric shapes are in human symbolic language. These basic forms - the square, the triangle – evoke stability, knowledge, but by disrupting their conventional presentation, Albers seems to question these very notions. Curator: Yes, and think of the implications of his Bauhaus background and later teaching posts! This wasn't just abstract aesthetics, it was also about accessibility and education. It attempts to redefine art’s purpose, placing art, design, and the lives of ordinary people at its center. Albers was also grappling with how these forms and philosophies had been misappropriated by the Third Reich. Art Historian: And how simple! Pale lines against a dark void. In this, I feel something elemental, like the very basic principles on which we construct our world - mathematical, philosophical even. The illusion hints at Platonic ideals: an absolute reality that our senses can never truly grasp. Curator: Absolutely. And the title "Twisted but Straight," itself presents that binary opposition. It encapsulates the duality inherent in modernity itself: the promise of progress undermined by persistent distortions of power and ideology. What seems rational on the surface may have been built on systemic injustice, and so he creates forms that make that visible, in order to prompt questions about what appears and what is "true." Art Historian: A powerful and compelling piece. It causes me to think of M.C. Escher in its use of paradox, challenging the viewer's preconceived notions of space and perspective. Curator: Ultimately, I appreciate the way that Albers pushes us to confront uncomfortable realities hidden beneath familiar surfaces, which, even today, we need to remain aware of. Art Historian: Agreed. Its beauty lies in the questions it prompts, rather than providing any easy answers. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.