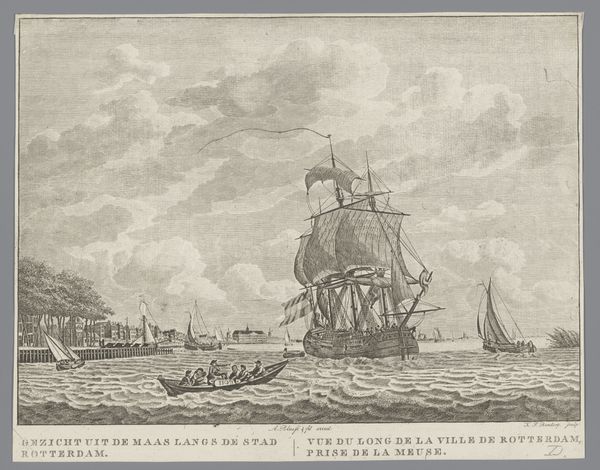

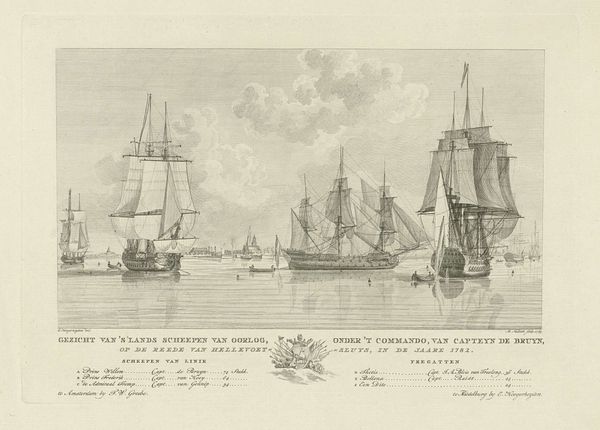

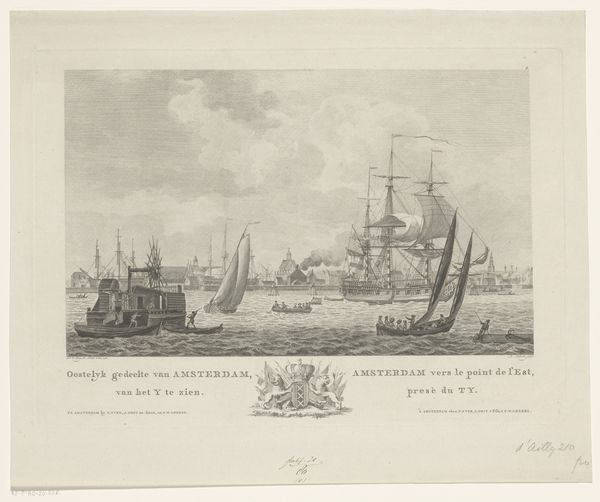

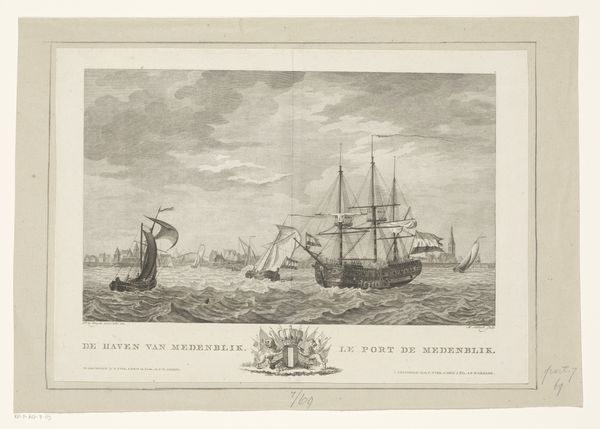

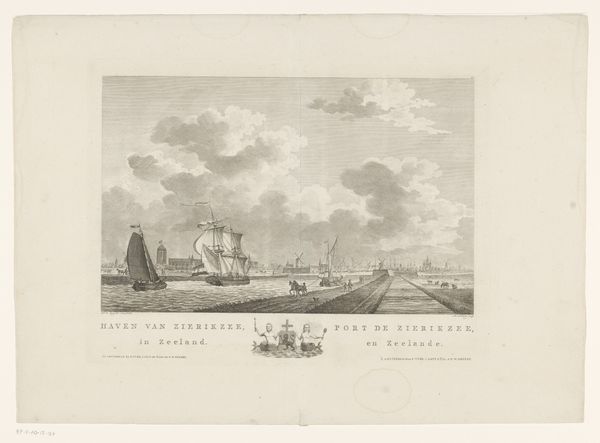

Dimensions: height 223 mm, width 283 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome to the Rijksmuseum. We’re standing before Carel Frederik Bendorp's "View of Vlissingen from the Sea Dyke," an engraving dating back to 1784. Editor: It evokes a sense of serenity. The delicate lines create a scene of quiet maritime activity, and I can almost feel the gentle sea breeze. Curator: Precisely. Observe the composition; Bendorp’s expert use of line directs our eye from the foreground boats towards the distant cityscape, demonstrating a clear understanding of perspective and depth. Note the balance achieved through the placement of vessels of various sizes. Editor: And consider the historical context. Vlissingen, as a major port city, played a vital role in Dutch maritime power. This image presents not just a pretty picture, but a glimpse into the economic and social fabric of the time, which would have involved the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. Who benefited from all this trade? Curator: An important question. Focusing on its formal aspects, the artist’s rendering of light and shadow with mere lines provides great texture and detail in the water and sky. Semiotics also allows us to decode the sailing ships, each with unique shapes that evoke cultural symbols and meanings related to travel. Editor: Absolutely. These ships are symbols of power and movement, yes, but what kind of power and whose movement? Thinking about this through an intersectional lens highlights the human element, bringing forward enslaved persons' stories, resistance, and agency. Curator: An interesting point. Notice, too, how Bendorp used a relatively limited palette in monochromatic engraving. His artistic mastery really shines when we scrutinize how he managed such expressive detail and shading with only line. Editor: In that vein, analyzing the work’s composition further exposes the underlying societal values it depicts: an orderly world sustained through exploitation, rendered as quaint simplicity by Bendorp’s artistry. What seems like a view also communicates implicit messages and narratives about the social reality of this 18th-century port city. Curator: Through your insights, we see beyond formal elements. Indeed, our appreciation of this 1784 engraving becomes multi-layered when examined with cultural context. Editor: Art history is never objective. It is always political.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.