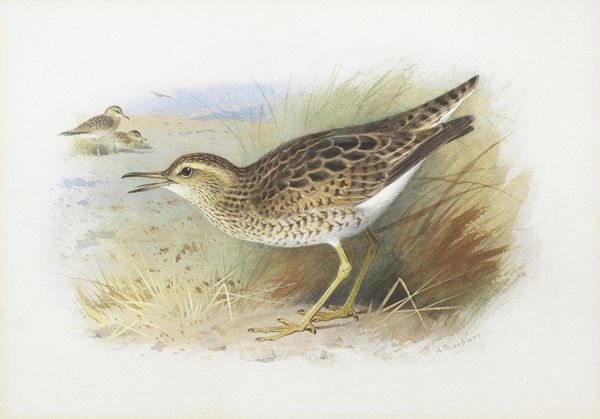

drawing, watercolor

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

watercolour illustration

#

naturalism

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 660 mm, width 480 mm, height 214 mm, width 317 mm, height 197 mm, width 317 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I find this watercolor, made around 1778 by Robert Jacob Gordon, surprisingly tender. There's something delicate and intimate in its rendering. Editor: Indeed. Even without knowing the title, “Turnix hottentotta,” one gets a feeling for this bird as a subject rather than just a specimen. There's an immediate impression of quiet observation. It evokes a sense of the artist having spent time simply watching it. Curator: It speaks to the period's evolving interest in natural history illustration, doesn't it? But the way Gordon captured the nuances in the bird's plumage and posture lends it a sort of vulnerable realism. These brown flecks and yellow ochre coloring of this particular specimen is especially well-executed and precise. Editor: I agree, and that's key. Gordon, a figure tied to the Dutch East India Company and exploration, here offers a counterpoint. The watercolor format itself feels gentler than strict scientific illustration. Its setting in a landscape contributes to the feeling of intimacy. Note, too, how its symbolic environment isn't ignored; there are tiny sprigs of grasses along the little ridge of turf upon which the Turnix rests and a few oblong stones to fill space near the illustration's baseline. It brings humanity to this seemingly scientific work. Curator: Certainly, it's less about dominance and more about understanding a place through its inhabitants. And the Dutch inscription at the bottom suggests this image wasn’t meant just for a scientific treatise, but potentially a more general audience curious about the Cape. Editor: Precisely. Images like this played a crucial role in shaping European perceptions of Africa. While colonial narratives often emphasized power and control, the intimate portrayal of this little quail opens up avenues for a softer view. These kinds of visuals helped construct a world back home. It speaks to an attempt at knowing—even, perhaps, possessing—a land by knowing its creatures. Curator: A bittersweet paradox, perhaps? Appreciating nature while simultaneously laying the groundwork for its exploitation through this impulse of claiming territory and specimens... Editor: Perhaps. But at the same time, images like this provide insight into a complex period, reflecting shifting perspectives toward the natural world and colonial encounter, both tinged with exploitation, to be certain. Thanks to illustrations like this, however, it doesn't all amount to wanton consumption. I still admire the image today, for how successfully it bridges scientific intention and aesthetic observation. Curator: A valuable reminder that visual records always speak to broader historical, cultural currents. It's remarkable how much emotional weight an image, however simple it appears, can carry across time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.