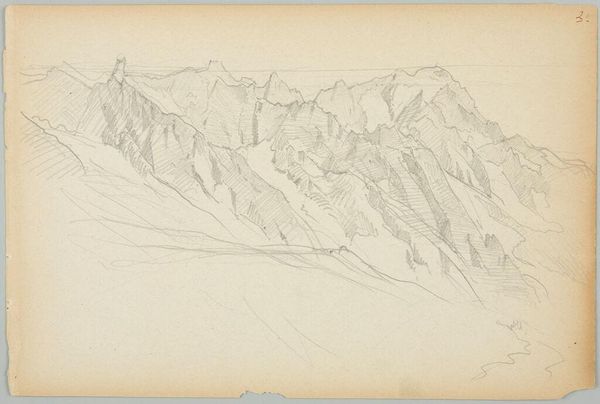

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

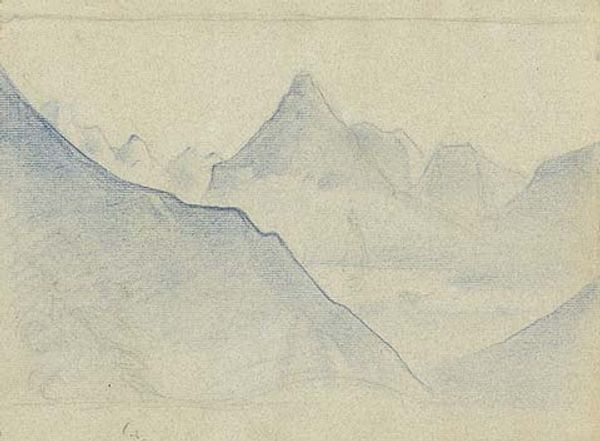

pen sketch

#

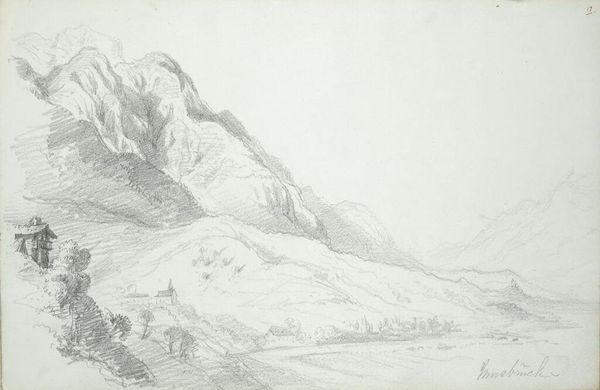

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

etching

#

pencil

#

realism

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

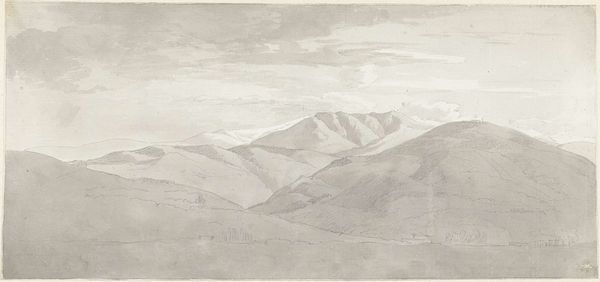

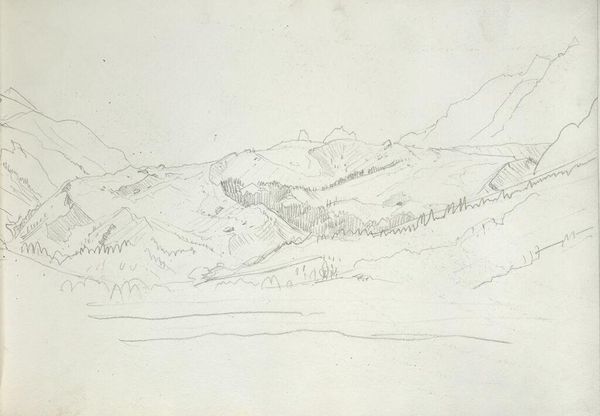

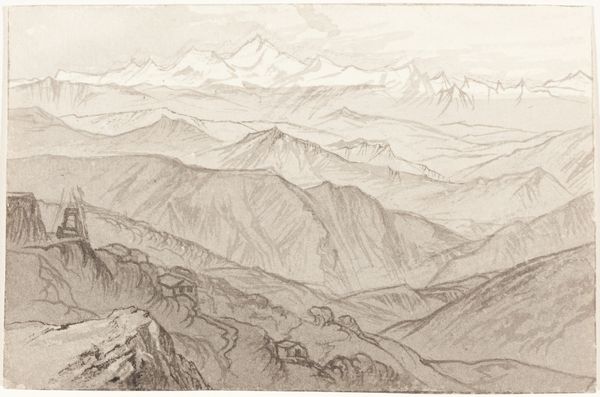

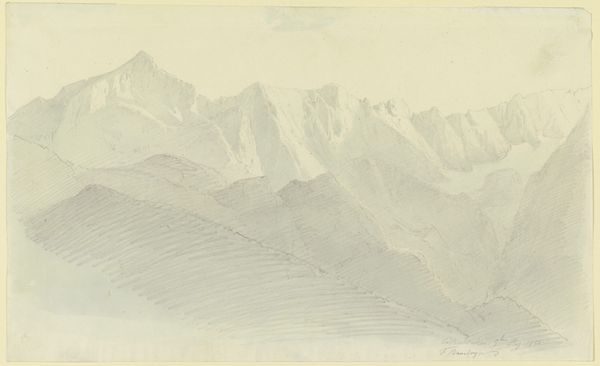

Curator: Welcome. Before us lies "Sketches of alpine ranges in Switzerland" by Józef Simmler, created in 1856 using pencil and ink. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: There’s something stark and lonely about it. It's primarily grayscale, depicting mountainous terrain that fades into the sky, making it look quite empty. A bit foreboding, really. Curator: The artist's choices are interesting. The medium itself, humble pencil and paper, speak to accessibility and portability. This could have been created on-site during his travels. Did he have a patron for the journey, who funded this practice? Editor: Possibly. Landscape art in this period reflects ideas about nationhood, especially in Switzerland, which was consolidating its identity in the mid-19th century. Did these sweeping views inspire notions of collective pride, of belonging? Also, the lack of human figures prompts questions about who gets to access this landscape, and what labour sustains its viewing. Curator: Indeed. And look at the technique—the repetitive, almost hurried lines used to create shading and texture. Perhaps that reflects the actual labor involved in representing such expansive scenery within the confines of the page. It's not about illusionism here, it’s more focused on observation and translation. What do you suppose was he aiming for? A memento for himself, or something more? Editor: Maybe it was both personal and political. Remember, Simmler was Polish, but studied art in several European academies, so his lens is interesting. Considering issues of imperialism and how travel could signify privilege and access to certain spaces during this time might provide further context to this and to Simmler’s cultural positioning. Curator: Absolutely, by choosing the relatively immediate and accessible mediums of pencil and paper, we see that Simmler makes no claims about an elevated vision; instead, this artistic practice situates him within an empirical process of looking, collecting data, and drawing conclusions in order to render what can't literally be captured in total. It is almost like visual knowledge gathering for a rising country. Editor: Ultimately, this seemingly straightforward drawing holds layered stories of nationhood, access, labor, and the very act of seeing and representing a space, a set of circumstances, which provides access to its many histories. Curator: And from a materialist perspective, it reveals how even the simplest tools, employed during exploration or nation-building, contain both practical application and complex social values within its production, the paper it's printed on and the source from where they're created.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.