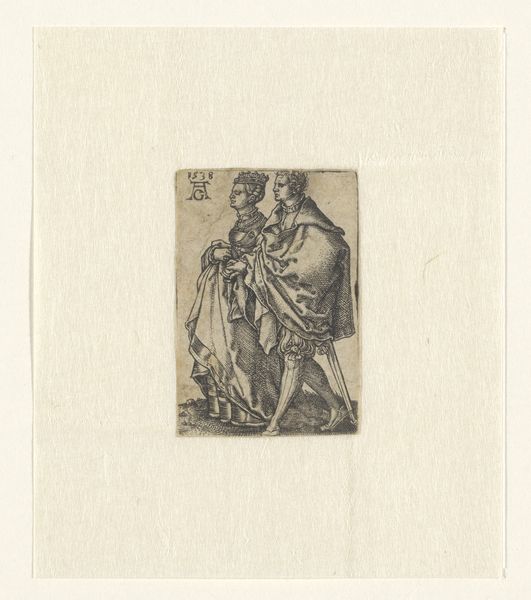

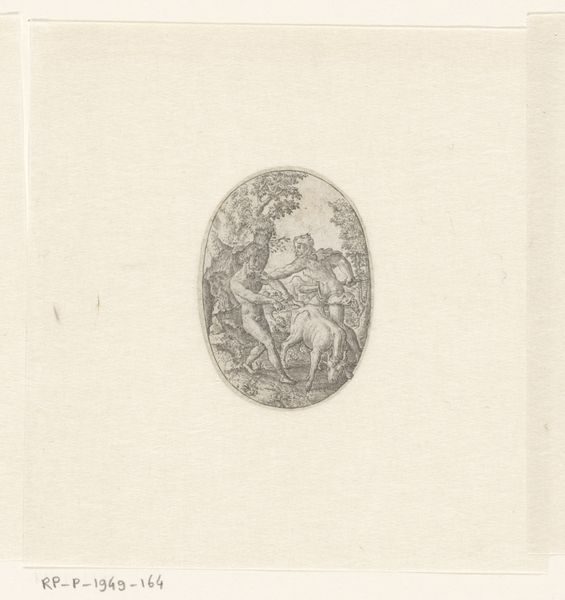

relief, sculpture, wood

#

animal

#

relief

#

landscape

#

sculpture

#

united-states

#

wood

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: 9 x 6 in. (22.9 x 15.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have a "Plaque," created sometime between 1880 and 1890 by James Priestman. It's currently part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art's collection. Editor: My initial impression is one of serene domesticity. The muted palette and detailed rendering of the animal offer a pastoral glimpse into rural life, but in a very stylized, almost idealized form. Curator: Indeed. It’s a wood relief, quite small in scale, that beautifully demonstrates a realism style typical of Academic art during that period in the United States. I am interested in the process Priestman went through carving each detail from wood. What kind of tools did he use? Did he use a reference for his work? What about the wood grain and source, does that speak to a local tradition, or was it meant for display among those of a certain wealth? Editor: Thinking about the iconography of the bull is fascinating. Across cultures, the bull can represent virility, strength, but also stubbornness and earthy groundedness. Placing it within a landscape – implied by the flora – gives it context; it’s an emblem of the American agricultural dream rendered in careful relief. The choice to present it almost like a cameo portrait, lends it a sense of nobility, doesn't it? Curator: I am compelled to consider Priestman's motivations. Wood relief requires time and skill – how was his labor compensated? And where did such pastoral images fit into a rapidly industrializing America? I can almost hear the debates that may have arisen between high art that depicts bucolic subject matter, and more pedestrian arts, like the wooden signs found above storefronts and taverns. Editor: The framing enhances the symbolic weight; it sets apart this humble, rustic image for consideration and elevates the scene. What sort of value systems are displayed here? Was it commenting on a nation’s shifting identity? Curator: Ultimately, these artifacts present many valuable ways to look at labor and the artistic landscape of 19th-century America, reminding us how entwined those concepts can become. Editor: It leaves me thinking about the staying power of symbols and the way humans consistently return to familiar visual tropes to communicate deeper values.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.