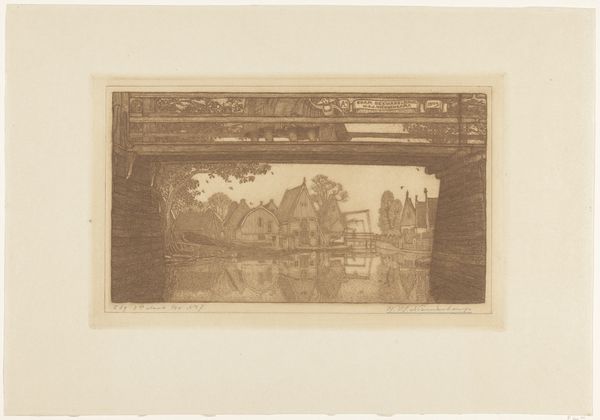

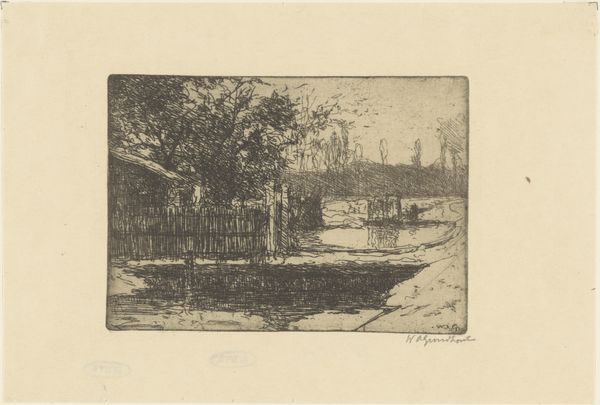

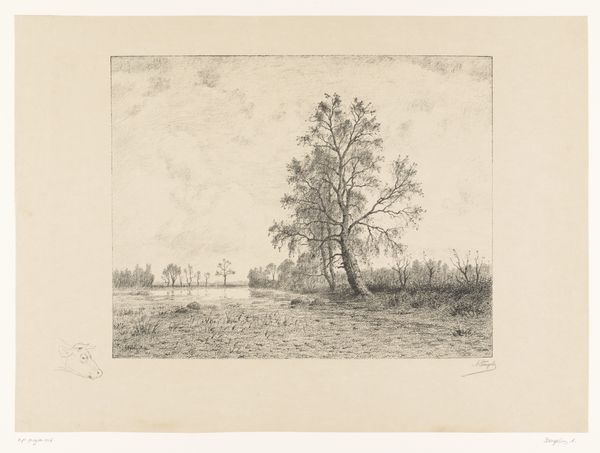

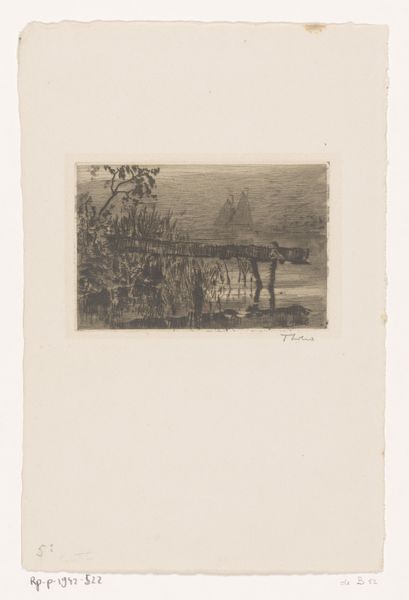

drawing, print, etching, paper, ink

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

paper

#

ink

#

linocut print

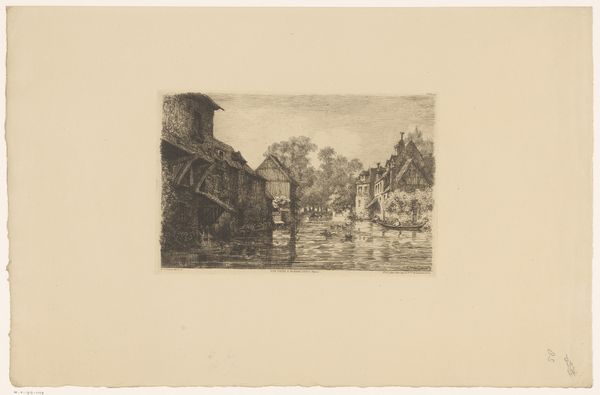

Dimensions: height 394 mm, width 555 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

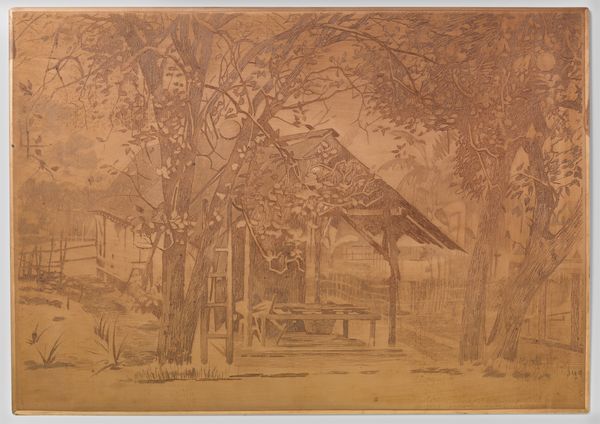

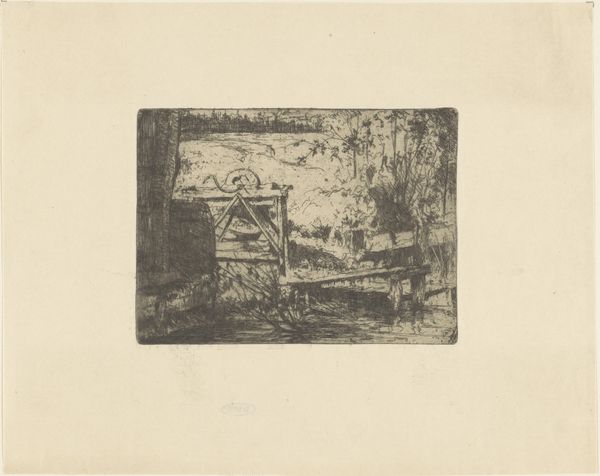

Curator: This subtle yet captivating work is entitled "De ophaalbrug Edam," or "The Drawbridge of Edam," tentatively dated to 1916, and crafted by Wijnand Otto Jan Nieuwenkamp. It’s an etching, ink on paper. What strikes you first about it? Editor: Well, immediately the intricate detail draws me in. The branches of the tree, for instance – each rendered with delicate lines, suggesting a quiet observation of nature and something of an invitation. Curator: That precision is characteristic of Nieuwenkamp's work. He was deeply involved with preserving traditional Dutch architectural subjects and scenes. He romanticized village life even when those ways were passing due to industrialization. This print reflects that cultural anxiety. Editor: There's a melancholic tone, isn't there? Bridges often represent transitions, connection, and the promise of new possibilities. But here, the raised drawbridge almost seems to act as a barrier. And with the old buildings on either side of the canal, one gets the feeling this place has become a time capsule. The symbols, however, are not all of despair. Water symbolizes unconsciousness and dreams, inviting the spectator to dream of the scene rather than walk through it. Curator: Precisely. In Nieuwenkamp's time, rural Dutch society experienced intense urban migration. The art of the era showed people actively wrestling with what would be lost or changed forever due to modernity. You could almost imagine he wasn’t just illustrating a bridge, but documenting the character of an entire epoch that would pass. Editor: It feels heavy with symbolism, then. Not just as a mere rendering of the physical world but as something deeper… a comment about a world on the verge of dramatic change, and perhaps even mourning the cultural world that modernity inevitably disrupts. It asks the question: What do we leave behind when we move towards the future? Curator: Exactly. We should be careful, I think, not to interpret this only through modern eyes. In some ways, prints like this served a functional purpose. Think of them as popular records of a shared cultural experience; or maybe ways to reflect on values from the past. Editor: Absolutely. Seeing these prints is also, in a way, participating in an act of cultural preservation. These symbols offer us insight into cultural memory and a vision of change. Curator: Indeed. Nieuwenkamp gives us more than just a visual of a bridge and a canal; he provides us with a view into the soul of a society. Editor: Thank you. Now I leave this place with the gentle melancholy of memory.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.