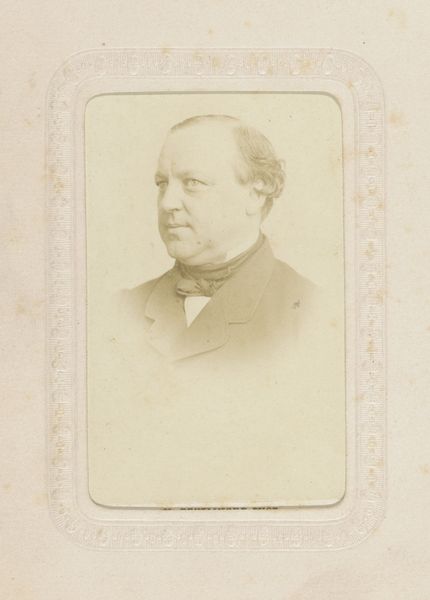

![[George Richmond] by John and Charles Watkins](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzRlMjBiYTg3LTk4MTUtNGVjMi04NDU5LThhZWYyYzgwODIzOS80ZTIwYmE4Ny05ODE1LTRlYzItODQ1OS04YWVmMmM4MDgyMzlfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

men

#

portrait drawing

#

albumen-print

#

profile

Dimensions: Approx. 10.2 x 6.3 cm (4 x 2 1/2 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

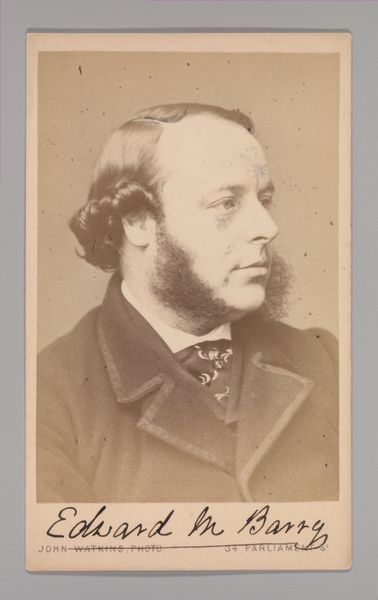

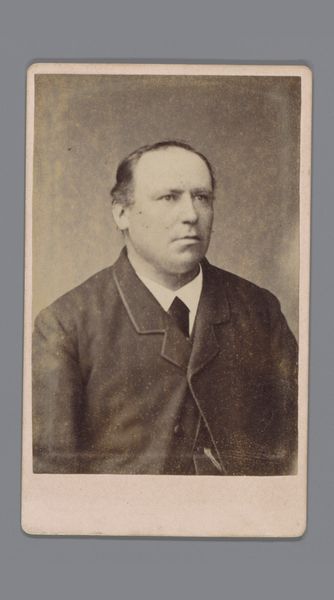

Curator: This albumen print, a photograph from the 1860s by John and Charles Watkins, is titled "[George Richmond]". Editor: It's incredibly subtle. The tones are so muted, it’s almost like a sepia dream. He seems lost in thought, peering into the middle distance as if reading tea leaves. Curator: Indeed. Albumen prints, popular then, use egg whites to bind the photographic chemicals to the paper, creating these lovely warm tones. It was quite a common portraiture medium, giving the rising middle classes a chance to immortalize themselves. Richmond, you’ll note, is shown in profile, a popular stylistic mode. Editor: And yet, there's a strange directness despite the profile. Maybe it’s in the intensity of his brow. He's got a very specific and almost severe look about him, don’t you think? A bit imposing? Curator: Victorian portraiture, in general, presented very deliberate poses to convey status, virtue, or intellect. Displaying oneself with confidence—almost severity—would’ve communicated respectability to the Victorian audience. A public image for consumption. The Watkins brothers themselves were known for photographing many members of parliament. Editor: Oh, you can absolutely tell! There's such care in his clothes. The lines of his jacket are soft, while the textures and contrasts hint at affluence, though done with British restraint. I'm just trying to imagine his story – who he loved, what he feared. He’s frozen in time and yet strangely present. Curator: And those carefully crafted details provided vital cues for Victorian viewers, telegraphing very specific messages about the sitter's position within society. Though that level of visual reading might be lost on a modern viewer at first glance. Editor: Perhaps. But maybe that stillness, that soft, almost dreamlike quality, lets us see past all that. It strips away the layers, revealing a sort of raw humanity— vulnerability, even. The overall effect softens the man while deepening his mystery. What a striking thing! Curator: I find it remarkable how these portraits serve both as reflections of an era and vessels of individual stories. A great example of photography becoming a new kind of social signifier in nineteenth-century Britain. Editor: Yeah, I was captivated by the texture. It’s soft and yielding. If he could talk now, what a tale he could tell of that now-distant, ever mysterious world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.