daguerreotype, paper, photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

french

#

daguerreotype

#

paper

#

photography

#

france

Dimensions: 22.5 × 18.5 cm (image/paper); 34 × 26 cm (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

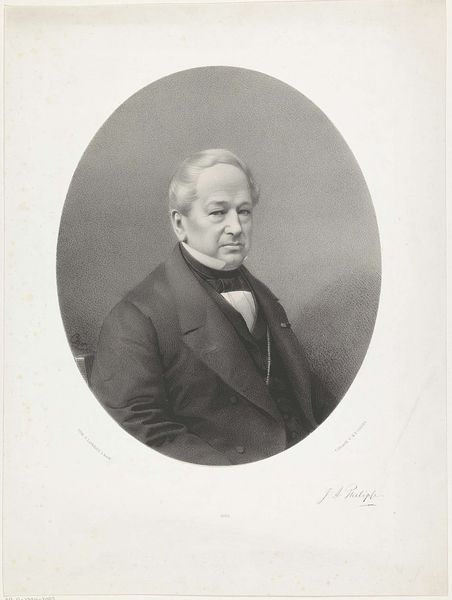

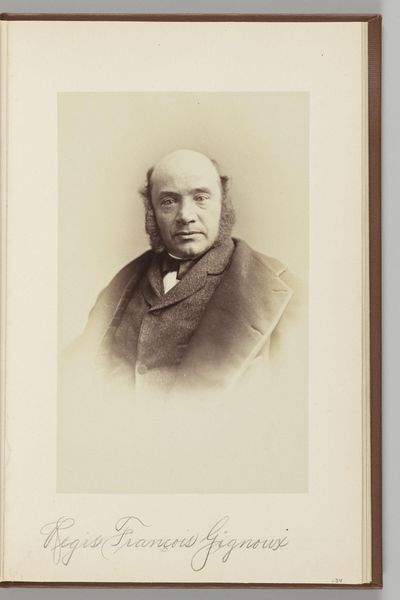

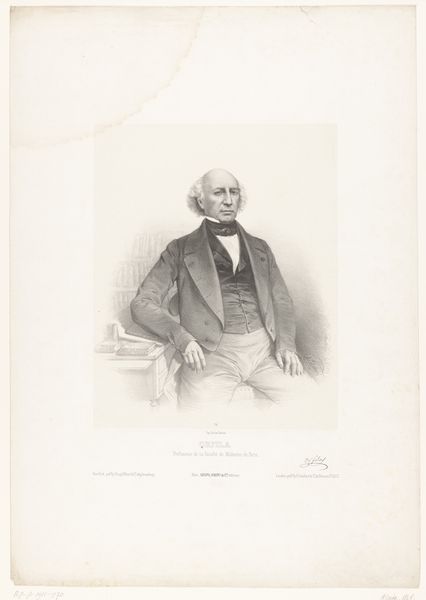

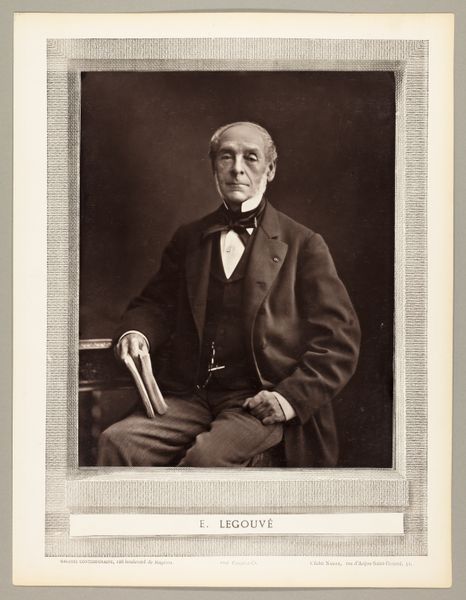

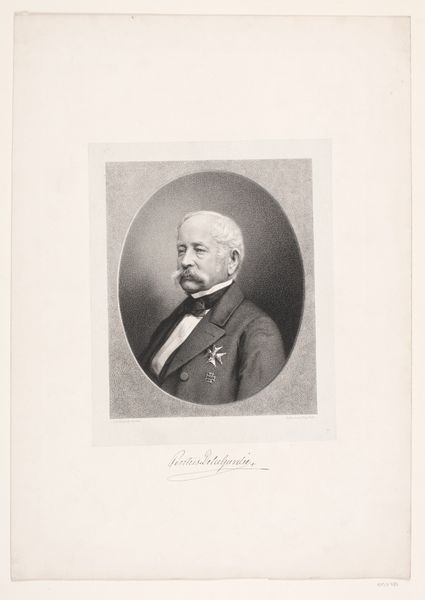

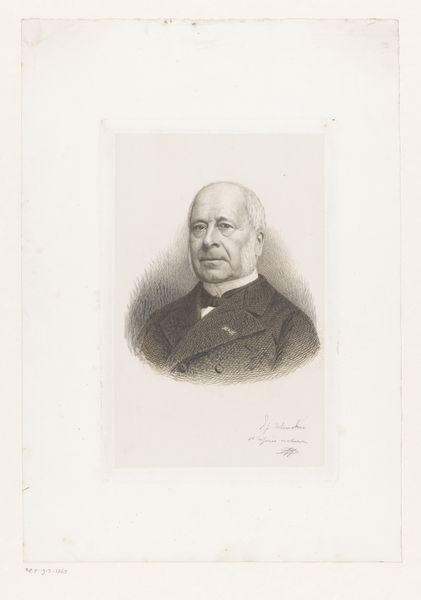

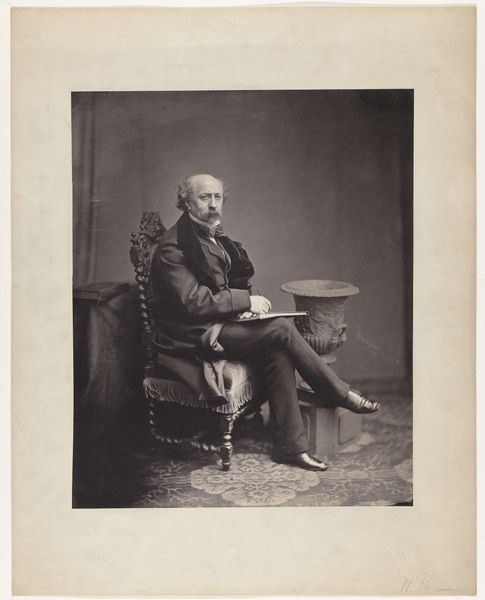

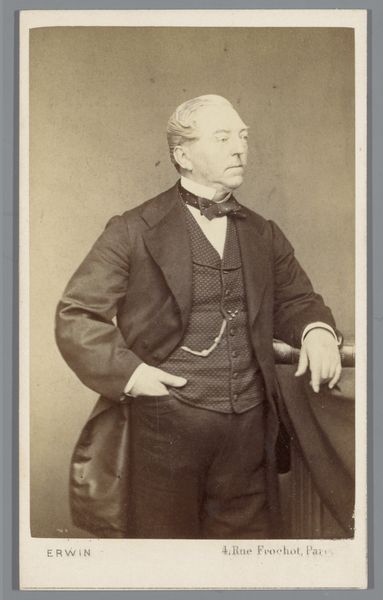

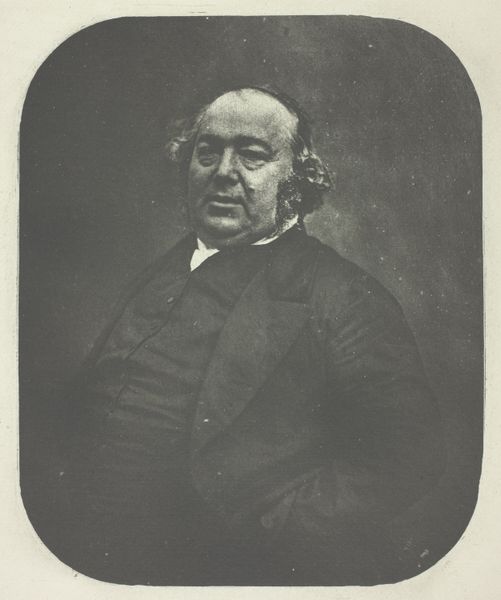

Curator: This is Nadar's portrait of Edmond-René Laboulaye, created sometime between 1853 and 1879. The artwork, now held at the Art Institute of Chicago, employs the daguerreotype technique on paper. Editor: My first impression is "serious." The sitter seems a bit weary, but resolute. I suppose that's nineteenth-century portraiture in a nutshell, isn't it? Curator: Indeed. The composition follows a predictable structure, focusing attention squarely on Laboulaye's face. Notice how Nadar employs a limited tonal range to subtly model form. The depth of field is shallow, rendering the background indistinct, which paradoxically throws his hands and lap into sharp detail, anchoring him within the pictorial space. Editor: The way the light catches the folds in his jacket is pretty spectacular for such an old process. I imagine sitting still long enough to make a daguerreotype in those days wasn't exactly a picnic, so this must've been an important occasion for him to endure the process! It really conveys the gravitas that must have come along with being photographed back then. Curator: Precisely. Daguerreotypes, given their unique materiality and inherent indexicality, offer an unmediated trace of reality, which no doubt lent an air of solemnity to the undertaking. There's also the issue of the image being a mirror-image, and how that complicates notions of portraiture. Editor: A mirror image! So that's not really how Laboulaye looked day-to-day. It makes me wonder how perceptions and memories shifted during the rise of photography as reality became something you could hold in your hands, but at least the truth would be reversed! That opens a delightful Pandora's box of philosophy... Curator: An accurate point about its implications on societal awareness. Nadar, a master of capturing character, transcends mere representation. He invites us to consider not just *what* we see, but *how* we see and what the photographic process itself does to the portrayal. Editor: It's strange, isn’t it, to think that this single sheet of paper lets us commune with someone across a century, like shouting across time! This object, so firmly in its time, lets us stretch out across the divide, no passport needed. Curator: Agreed. And hopefully, with new perspectives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.