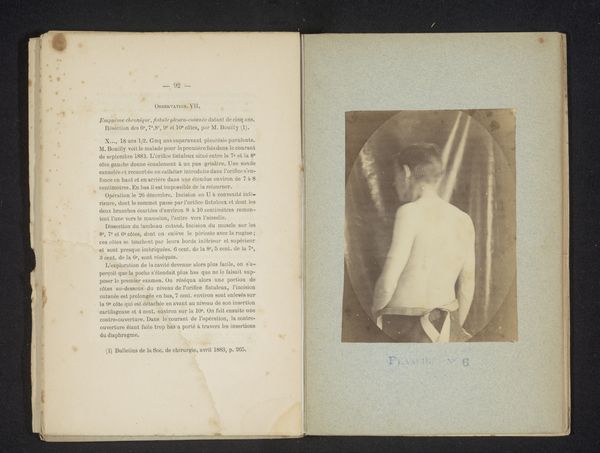

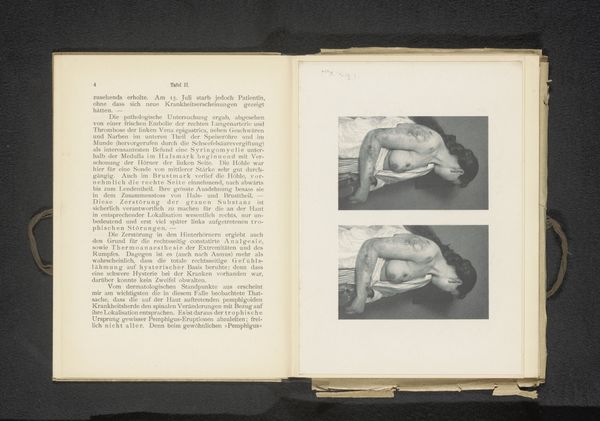

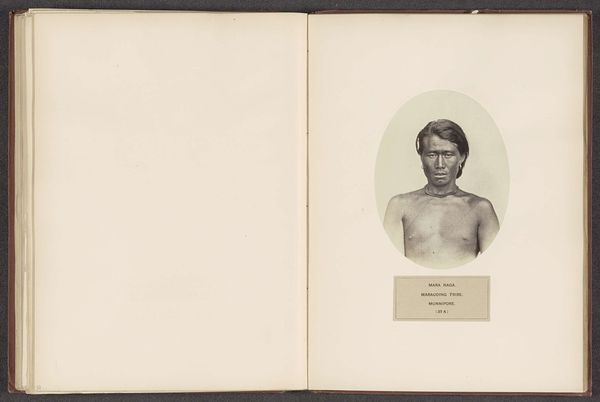

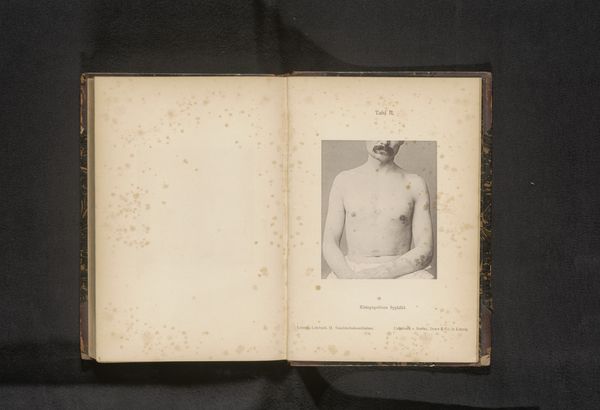

Man met ontbloot bovenlijf, met een litteken aan de rechterkant van zijn borst before 1885

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

academic-art

#

nude

Dimensions: height 138 mm, width 105 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have an arresting gelatin-silver print titled, "Man met ontbloot bovenlijf, met een litteken aan de rechterkant van zijn borst"—or "Man with a bare torso, with a scar on the right side of his chest"—taken sometime before 1885. Editor: It's stark. The figure’s gaze, the pale skin...there's something inherently vulnerable and quietly defiant in the image. The lighting almost sculpts the contours of his torso, accentuating the scar. Curator: Indeed. Such medical photography served specific purposes then, not just for clinical records, but also influencing understandings of the human form, disease, and ideas of physical perfection versus imperfection within academic and public spheres. Editor: That scar speaks volumes, doesn't it? It's not merely a physical mark; it becomes a symbol of struggle, survival, or even a specific ailment of the time. Photography during that era often objectified the body. Was this an attempt to scientifically record a malady, or perhaps, offer a glimpse into the human experience of that patient, perhaps even to immortalize their endurance? Curator: It could be both. Medical imagery was undeniably connected to societal anxieties about health and mortality. There was this tension, this interplay between clinical detachment and an attempt to capture the person beyond their affliction, further legitimizing these sorts of studies through broader cultural engagement. Editor: I can see that. The composition almost has an almost classical feel to it—but the scar interrupts that immediately. It challenges the viewer. You can’t view this in a solely aesthetic sense. It has an almost sacred feeling attached to it too though because scars represent some experience of transcendence that the bearer goes through Curator: The photograph stands, I think, at this interesting intersection of scientific study and early attempts to engage a public audience. Editor: Precisely. The scar, the light, the almost vulnerable expression. It becomes less about clinical coldness and becomes almost a beacon to future observers, about perseverance in adversity, even in photographic format. Curator: Exactly. It allows us to look back and ask some questions to better see not only our understanding of our history and where we are now, but it causes me to be curious of who the Man in this portrait was, too. Editor: Absolutely. A visual portal, into how images once codified complex, societal attitudes and, through symbolic reading, gives space for empathic considerations that continue today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.