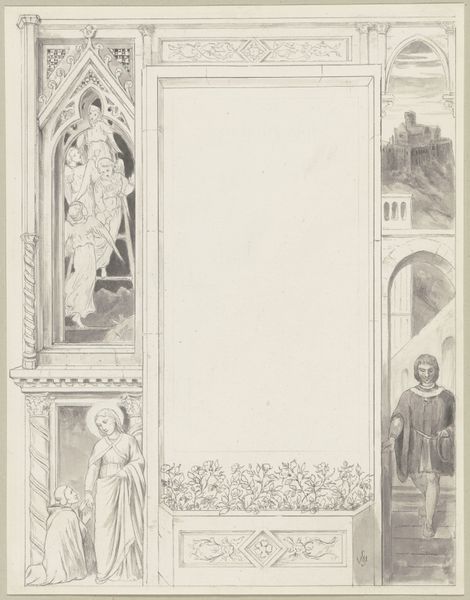

![Irmela. Eine Geschichte aus alter ZeitIllustration zu_ Heinrich Steinhausen, „Irmela. Eine Geschichte aus alter Zeit“, Prachtausgabe, Leipzig_ Georg Böhme, [1884], Titelblatt by Wilhelm Steinhausen](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzRjZTczZTgwLTRlNDAtNDc1NS1iZDgwLWJiMTY4ZjY1Mzc4My80Y2U3M2U4MC00ZTQwLTQ3NTUtYmQ4MC1iYjE2OGY2NTM3ODNfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

Irmela. Eine Geschichte aus alter ZeitIllustration zu_ Heinrich Steinhausen, „Irmela. Eine Geschichte aus alter Zeit“, Prachtausgabe, Leipzig_ Georg Böhme, [1884], Titelblatt c. 1884

0:00

0:00

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have Wilhelm Steinhausen's "Irmela. Eine Geschichte aus alter Zeit," created around 1884. This drawing, made with pencil and ink, served as the title illustration for a lavish edition of Heinrich Steinhausen's "Irmela". Editor: It feels...ethereal. Like a faded memory, or a scene from a dream. There's this sense of gentle sorrow, almost, in the soft lines and muted tones. It reminds me of a very refined ghost story. Curator: Yes, I see that. Steinhausen was working within the Romantic tradition, which often leaned into emotional intensity and the evocation of specific moods. You notice how the architecture, vaguely medieval, frames a large empty space, suggesting a stage for some unfolding drama? It is representative of its time, when nationalism spurred great interests in a German-centric cultural memory. Editor: Precisely. The figures contribute so much to this. Those women on the left, are they mourners? They look rather grief-stricken. It feels so personal, this quiet moment, like walking in on someone's private contemplation. But tell me more of the "Irmela" the artwork is related to. Curator: Heinrich Steinhausen's "Irmela" weaves a tale set in the Middle Ages. He focuses on love, loss, and redemption amidst courtly life. Wilhelm’s drawing encapsulates all these prevalent themes found in his brother's literature, creating this symbolic gateway to an age defined by rigid class structures and prescribed gender roles. Editor: Do you think the lack of vibrant color contributes to that sense of constraint? As if all emotions and histories depicted here are muted or repressed somehow? Curator: Certainly. The monochrome palette emphasizes restraint, almost as if to highlight the limitations imposed on women in those societal frameworks. Furthermore, its creation as an illustration underscores its purpose. It wasn’t meant to be the art piece, but part of something greater. The role of women depicted further drives home that idea of existing only in relation to something, not in and of themselves. Editor: What an interesting lens through which to understand the piece! Looking at it now, I keep noticing the negative space. Curator: The void invites interpretation, wouldn't you agree? Steinhausen asks viewers to project their feelings, experiences, and even their identities onto it. It reflects the era’s attempt to negotiate an evolving German identity in relation to past narratives. Editor: Absolutely, it makes it all the more timeless. Curator: A powerful image, even over a century later. I'm gratified it prompted such reflections. Editor: Agreed, I'm leaving here seeing the artwork, and our modern society in a completely new way.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.