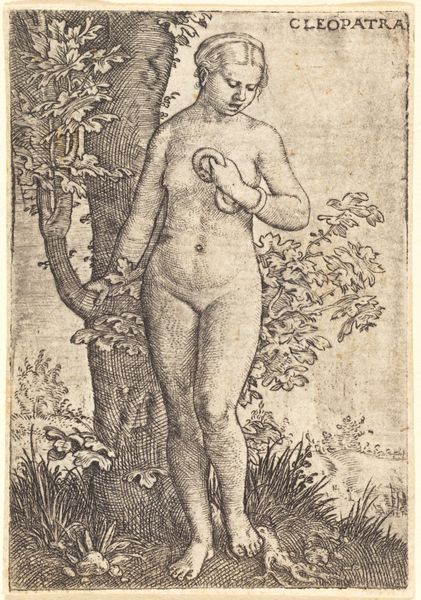

drawing, print, etching, paper

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

figuration

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

nude

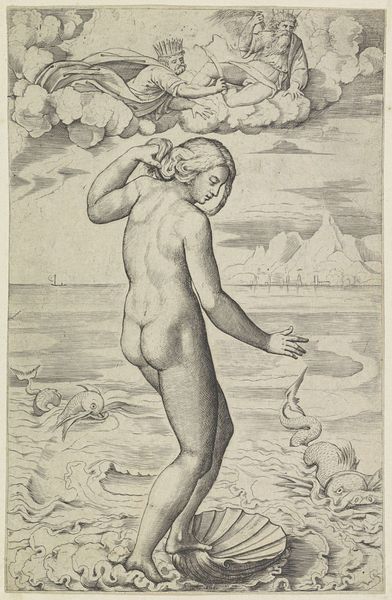

Dimensions: 284 × 111 mm (image/plate/sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Standing before us is "Eve," an etching by Daniel Hopfer, likely created around 1522. It's rendered in print on paper, showcasing Hopfer's mastery of the etching technique. Editor: It’s striking how Eve averts her gaze, a gesture suggesting shame, or perhaps introspection, in the moment of decision. It really speaks to the moment right after, or perhaps during the act, or what follows the first sin, the banishment... Look at those skies up there... The dark-etched shading is like impending doom. Curator: The composition certainly evokes emotional weight. We must remember that this scene carries significant cultural meaning for a 16th-century audience. Hopfer, in depicting the biblical Eve, taps into existing iconography and understandings of feminine identity. Editor: Absolutely. This Eve exists at a critical nexus of theological doctrine and patriarchal anxiety. And what’s so interesting about how these images were being spread and used during the rise of printmaking to advance a clear, often dogmatic point of view. Was the choice to create an etching a matter of availability, or perhaps aesthetics, given it was only around 10 years into Hopfer doing such artworks? Curator: The medium, though utilitarian, amplifies its cultural penetration. Hopfer's etching demonstrates the power of visual rhetoric at the time, making theological themes more readily available and digestible for a wider audience, than maybe a painted mural in a church. The symbol is very present through form. It is there to be interpreted, decoded. Editor: Note how the nude figure becomes a subject of debate and social control through images in broad distribution like this. Think of how these prints entered the visual ecosystem of 16th century Europe, influencing perceptions of morality, gender, and faith. Curator: It's hard to believe that Hopfer probably used iron plates, a novel method, to create this depth and shadow, but one thing we know is the legacy of this symbolism continues. Editor: Indeed. Seeing how Hopfer’s work functions as a kind of mirror, reflecting societal anxieties about morality, knowledge, and representation itself, can enrich our understanding of the era. Curator: Definitely! The intersection of religion and societal structures, as embodied in visual forms, unveils continuities and transformations of symbols throughout history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.