Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

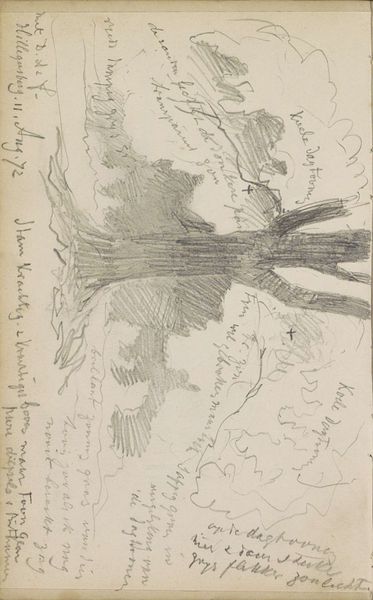

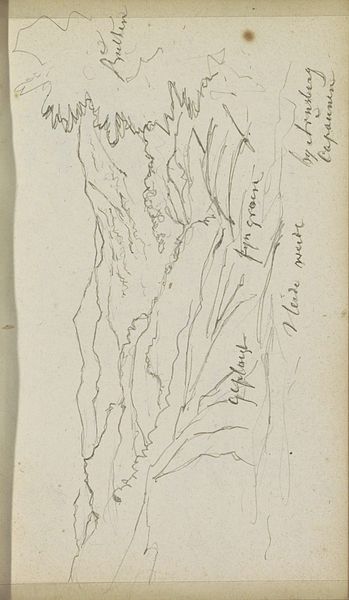

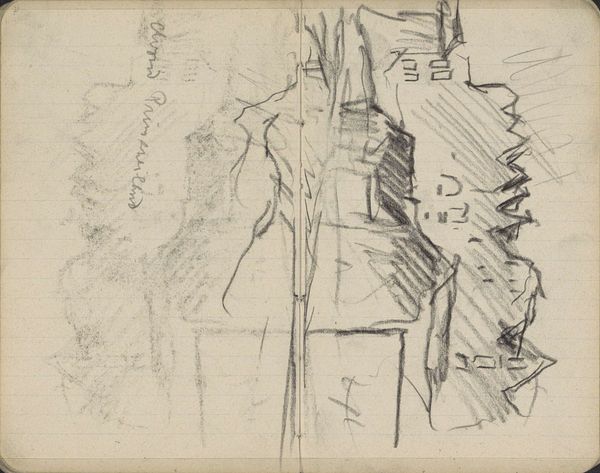

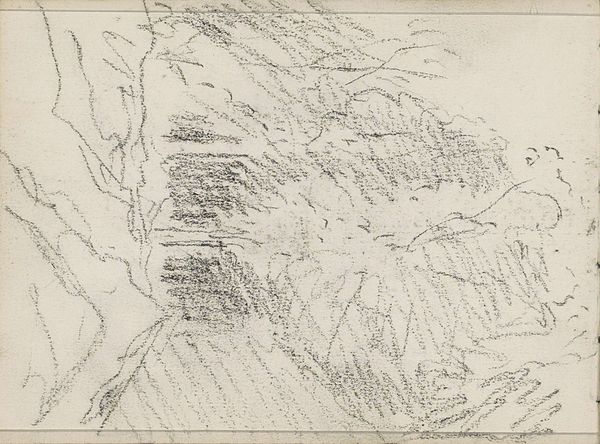

Editor: We’re looking at “Kasteelruïne op de Desenberg bij Warburg,” a pencil drawing made after 1854 by Johannes Tavenraat. It's a sketch of a castle ruin. I’m struck by how fragile and fleeting the lines are. What stands out to you about this work? Curator: What interests me most is the process itself. Look at the hasty pencil strokes, almost frantic in places, contrasted with the meticulous detail given to the crumbling stonework. This isn't just about depicting a ruin; it's about the labor involved in seeing, recording, and consuming the visual spectacle of decay. Editor: So, you're saying it's about the act of drawing, not just the subject? Curator: Precisely. Consider the social context. Romanticism was obsessed with ruins, connecting them to notions of lost empires and fading power. This drawing participates in that, but it also reveals the means of production. We see Tavenraat grappling with materiality, translating stone into line. The frottage technique gives a textural depth that hints at a transfer of the material presence of the site to the artwork. Editor: The artist uses the medium to represent the historical context, then? Curator: Absolutely. This process isn't neutral. It highlights a certain way of viewing and owning the past. It makes you question, "Who benefits from the romanticization of decay?". This focus shows that even in an innocent-seeming sketch, there's an examination of labor, consumption, and the making of cultural memory. Editor: I never thought about a drawing of a ruin as a product of labor. Curator: Seeing art this way reframes how we perceive its value, pushing us to look beyond the image and delve into the complex network of its production.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.