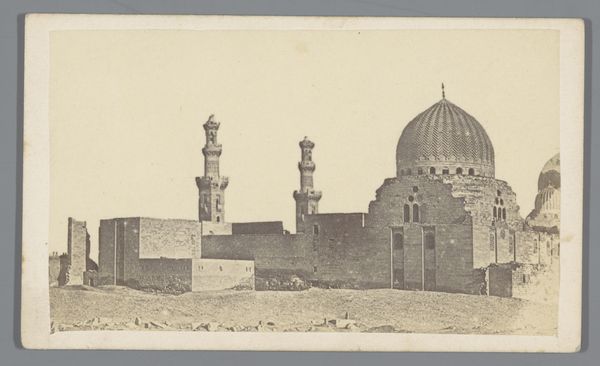

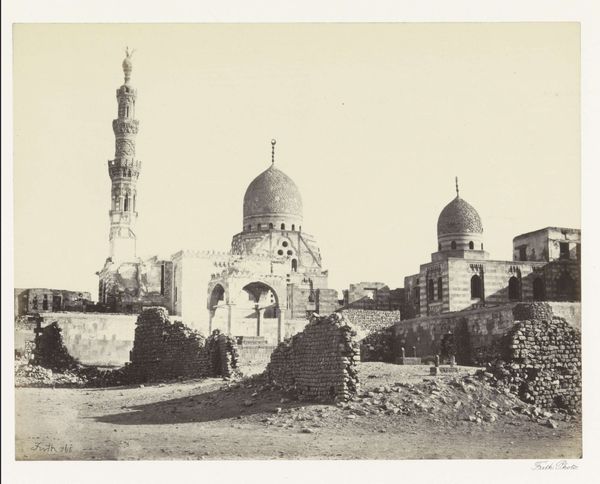

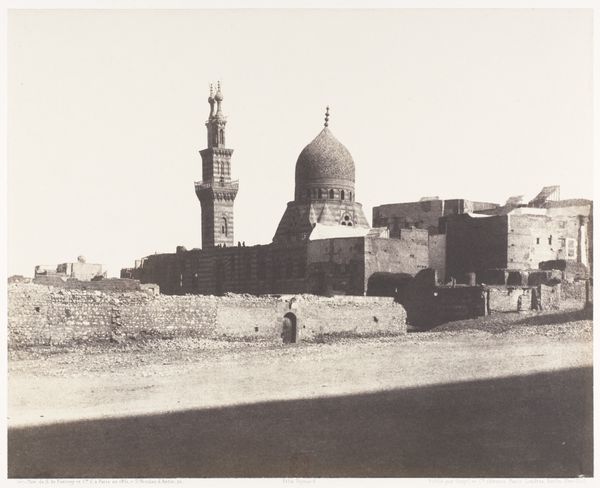

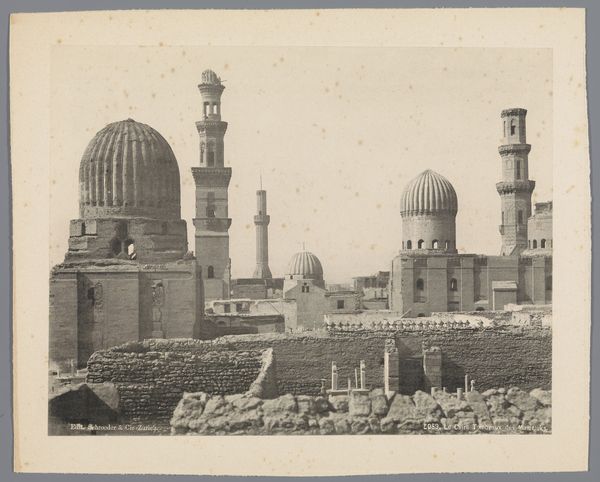

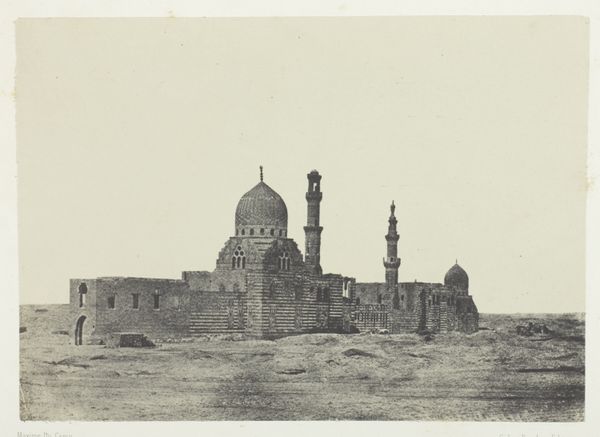

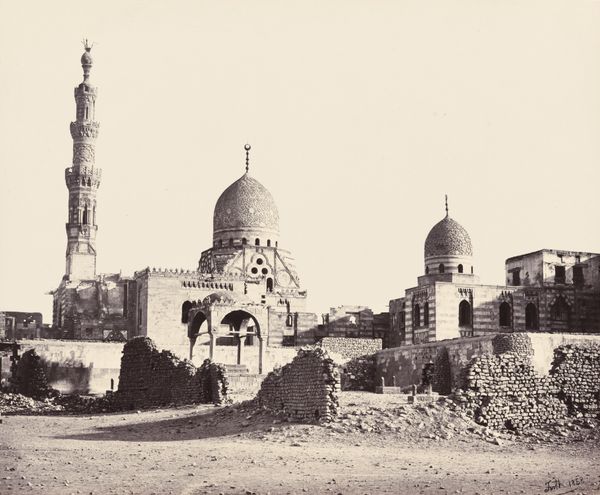

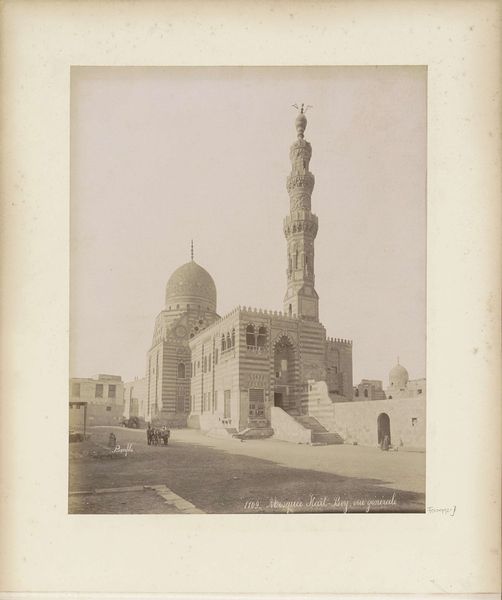

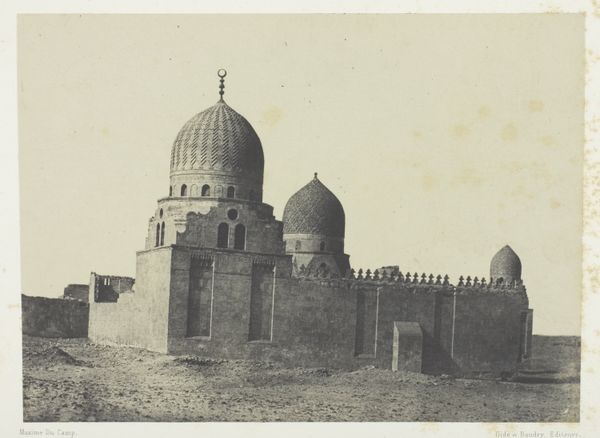

Le Kaire, Mosquées d'Iscander-Pacha et du Sultan Haçan 1851 - 1852

0:00

0:00

print, photography, architecture

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

islamic-art

#

architecture

Dimensions: 23.7 x 30.6 cm. (9 5/16 x 12 1/16 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

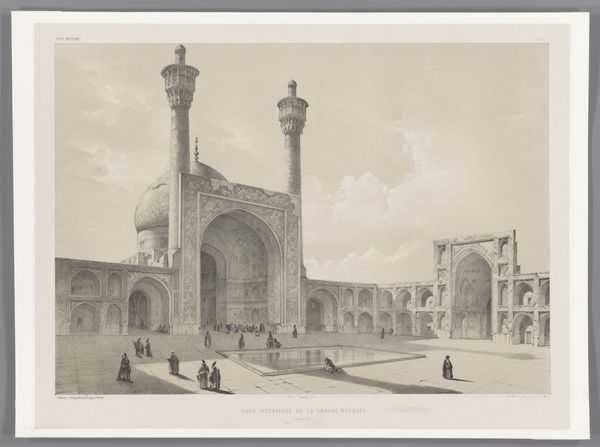

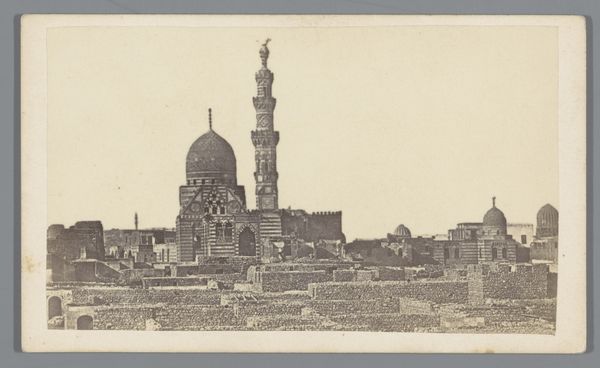

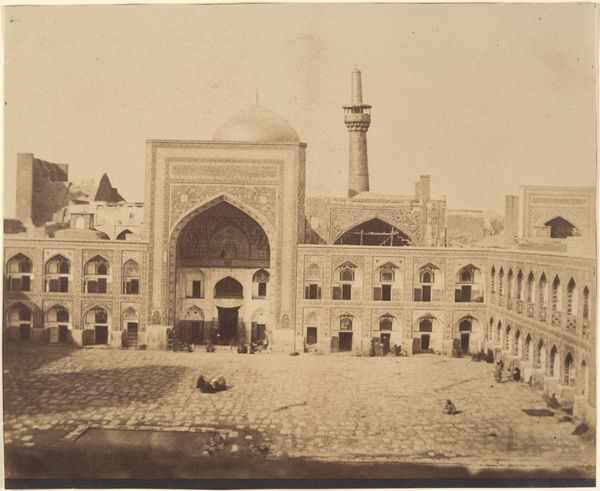

Curator: Welcome. The piece before us is Félix Teynard's photographic print, "Le Kaire, Mosquées d'Iscander-Pacha et du Sultan Haçan," dating back to 1851-1852. It’s part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection. Editor: My initial impression is one of serene stillness. The soft, sepia tones give it an ethereal quality, and the composition, while detailed, feels almost dreamlike. There’s a weight and presence communicated in the architecture but a simultaneous fading, owing to the photograph’s tonal range. Curator: Indeed. Teynard's work is remarkable for its documentary value and also its role in shaping European perceptions of Egypt. He was part of the scientific and artistic contingent accompanying an archaeological mission. His photographs like this one presented architectural wonders to the West, informing scholarship, imperial ambition, and orientalist fantasies. Editor: Thinking about it through a postcolonial lens, it is really worth discussing how the framing of these structures impacted not only architecture but also perceptions about the individuals connected to Islamic Art during that time. The act of documenting these majestic mosques inherently assigns value, even fetishization. Who exactly was it assigning value *for* and what narratives were simultaneously getting erased from the frame? Curator: Exactly. It’s not a neutral document but a curated view. Consider the sharp focus on architectural details – the minarets, the domes. They are presented almost as specimens, divorced from their lived reality and presented for external consumption. Teynard aimed to accurately record these structures. Yet, we must remember that what we perceive as accuracy is also shaped by cultural biases and the very act of representation transforms its subject. Editor: This photograph feels laden with that transformational power. It’s essential to deconstruct it—unpacking not only the technical achievements but also the potential layers of orientalism and appropriation present. These historical documents shape the narrative for future generations and the critical interrogation becomes increasingly necessary. What does Islamic art truly mean here? How has the label itself potentially obfuscated more nuanced dialogues about artistic expression within Islamic societies? Curator: Absolutely. These photographs were meant for circulation and served very specific purposes. Looking at them today we can question the ways the mosques were othered and aestheticized simultaneously. Editor: Thank you for giving a social and historical background to the piece; it has certainly given me another perspective on the function of the photograph in colonial discourse. Curator: Thank you, reflecting on these complexities enhances our comprehension of art and its lasting influences on societal viewpoints.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.