print, daguerreotype, photography

#

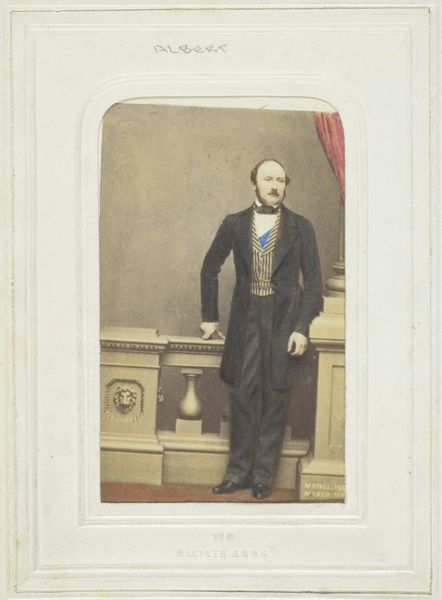

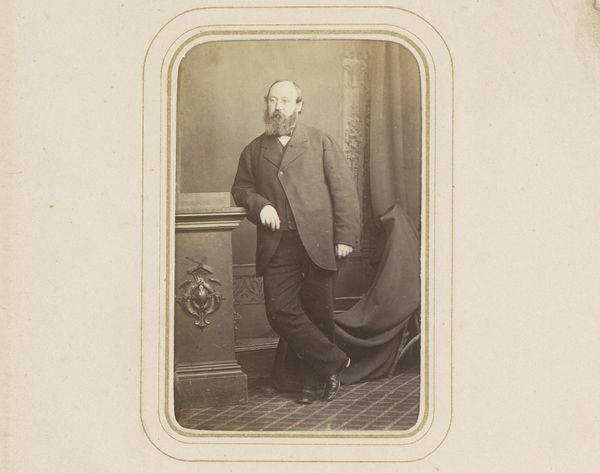

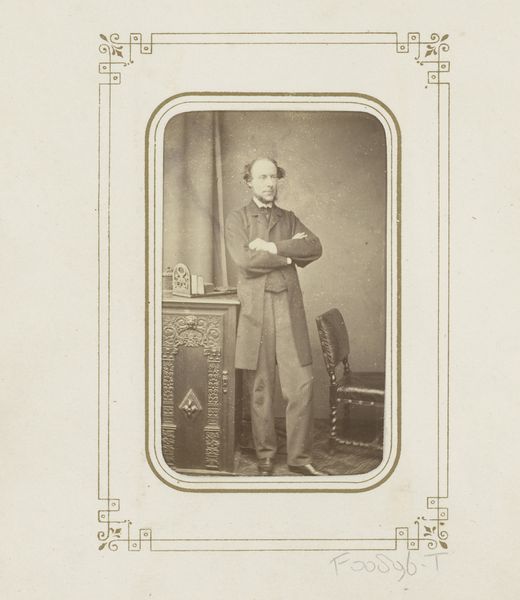

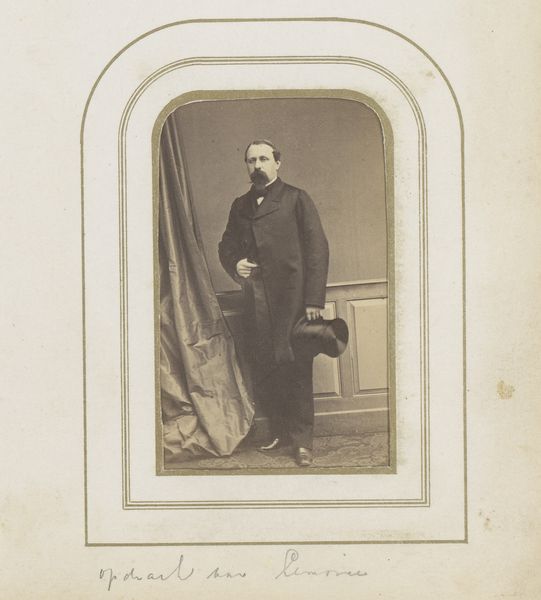

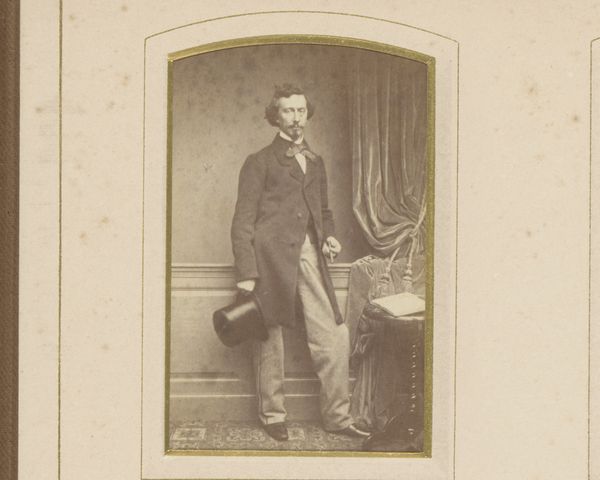

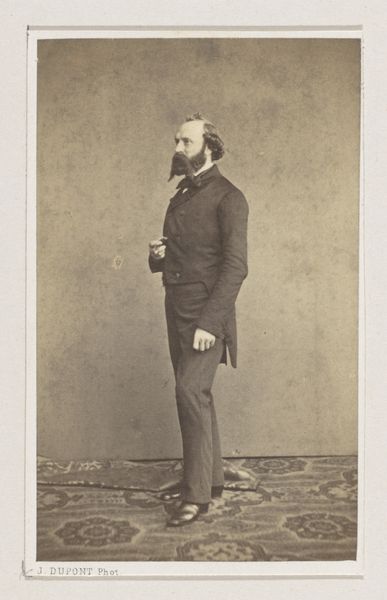

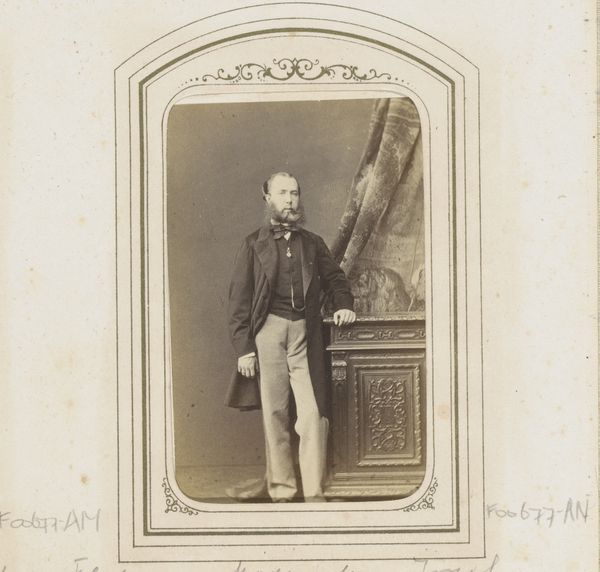

portrait

# print

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

men

Dimensions: 8.5 × 5.6 cm (image/paper); 10.5 × 6.3 cm (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Let’s talk about this daguerreotype, "The Crown Prince of Prussia," created by John Jabez Edwin Mayall in the 1860s. It's currently housed here at the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: He certainly looks every bit the Prince! So stoic, like a perfectly composed chess piece, arms crossed with what looks like equal parts impatience and calculation. I find the sepia tones oddly charming, softened by a touch of pink in what must be the hand coloring on the curtain fabric. Curator: The daguerreotype was an early photographic process; the image is created on a polished silver-plated copper sheet. These photographic portraits provided an expanding middle class access to portraiture, democratizing representation even of royalty. It’s fascinating how this particular image exists as a print, highlighting how even emerging technology could be quickly and broadly reproduced via existing means. Editor: Fascinating! To think that someone like me could have a somewhat identical twin of Prussian royalty from across the ocean decorating the parlour. Did this change portraiture itself, I wonder? All this efficiency, I'm sensing less the regal authority, more like mass-produced nobility ready to be shipped and consumed. What kind of work went into its production, though, beyond the obvious posing and daguerreotype-making itself? Curator: Absolutely! You hit on the crucial aspect here. Daguerreotypes, though pioneering, involved considerable labor: silver polishing, chemical preparation, and meticulous development processes. In order to broaden access to photography in general, innovations in faster shutter speeds were needed to streamline image capturing times to cut down costs, to shorten the time individuals were required to stand still. And, the hand-coloring certainly contributes additional value and production time. The labor component cannot be ignored. Editor: Indeed, it’s all very romantic until one gets mired in labor and materials. Even so, seeing this crown prince cast against a manufactured background and framed in a slightly off-kilter setting allows us to see him from this remove and imagine, well, his everyday struggles. To the extent that the process itself feels almost playful as much as professional. I might just be projecting a modern sensibility though. Curator: Perhaps! Ultimately, Mayall’s piece merges industrializing photographic technologies with the traditions of painted portraiture, while simultaneously exposing the labor of making the aristocratic image itself accessible to a broader public. Editor: Well, thinking of democratizing image creation through a materialist lens definitely provides, if you will, a regal understanding of all the layers. Thank you for that!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.