drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

pencil

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

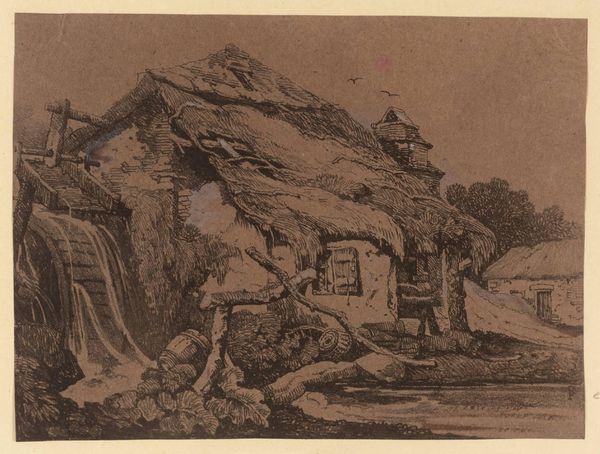

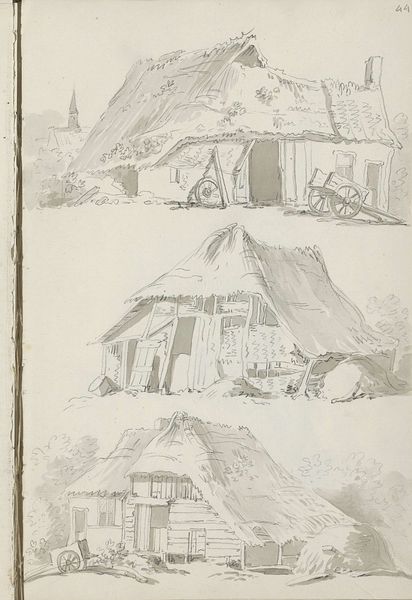

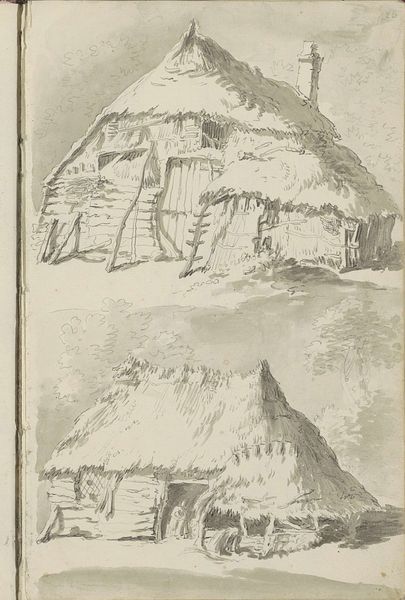

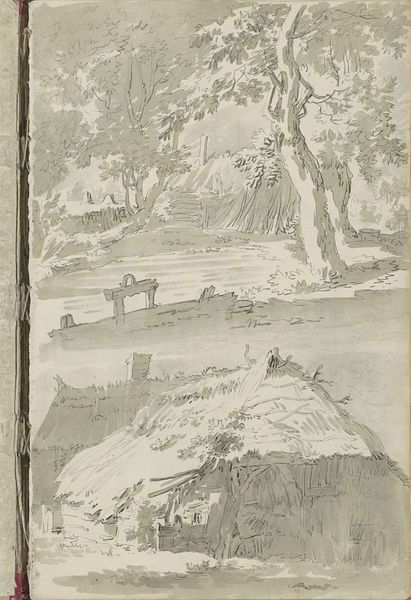

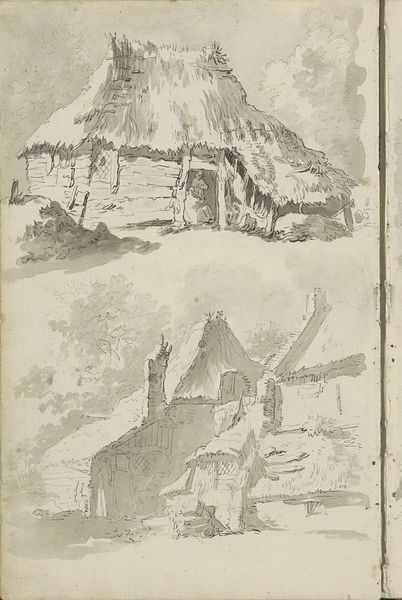

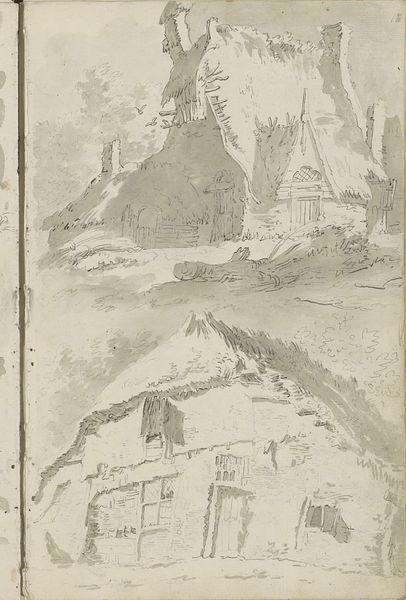

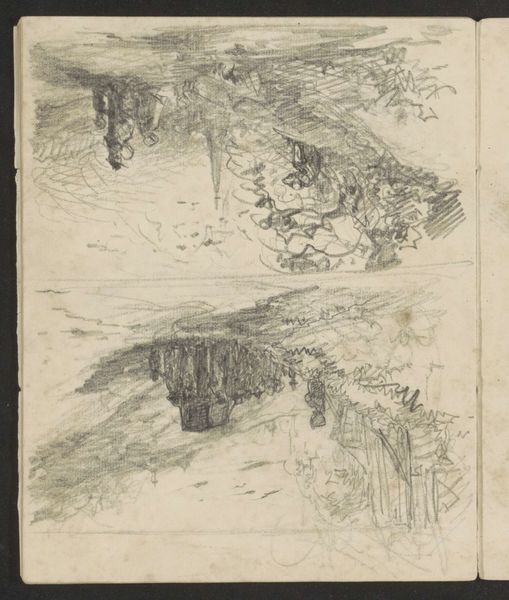

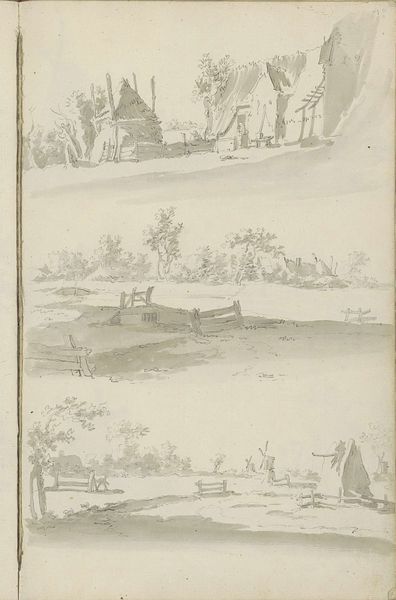

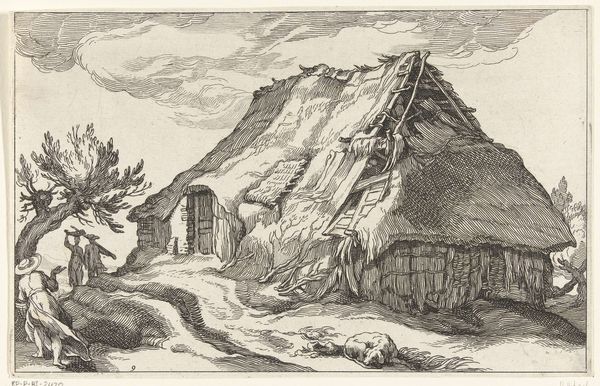

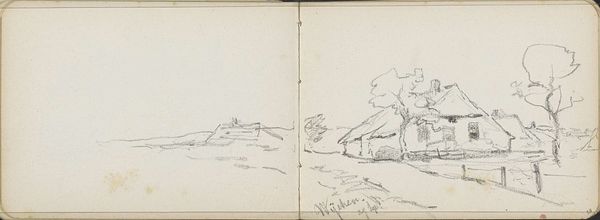

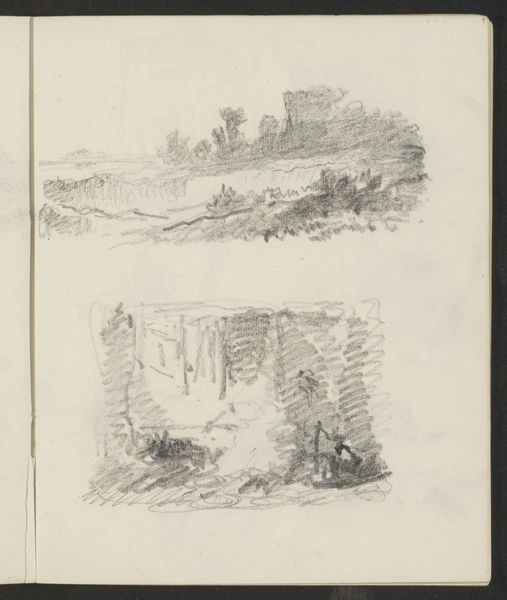

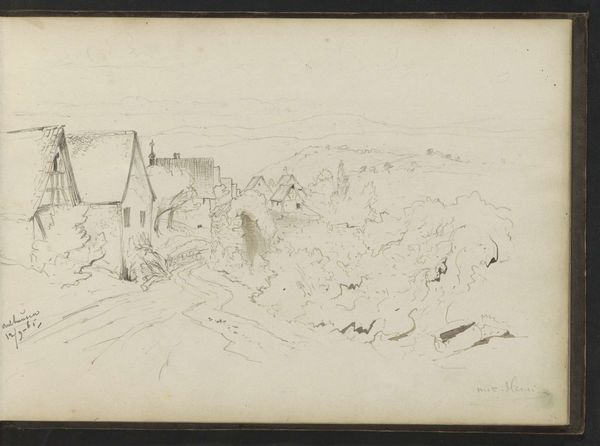

Curator: Let’s take a look at this drawing, "Boerenschuur en gekapte bomen," which translates to "Farm Barn and Cut Trees." Barend Hendrik Thier created this landscape around 1780-1800 using pencil on paper. Editor: The composition is interesting. The three sketches give a sense of observation in stages, or perhaps three slightly different viewpoints of a similar scene. I'm immediately struck by how spare it is, yet evocative. There’s a feeling of precarity in the sketch itself – the wispy lines and skeletal quality of the structures hint at a fragility, a tenuous hold on existence. Curator: Yes, observe how Thier's mastery lies in suggesting volume and texture through delicate pencil work. Note the hatching and cross-hatching used to delineate the thatched roofs and the rough-hewn timber of the barns. The negative space becomes as important as the drawn lines themselves in conveying form. Editor: What stands out to me is the state of things. "Cut trees," the drawing is titled. It begs the question: what happened here? Were these homes ravaged by some war, or were people struggling financially and didn’t have the means to care for things properly? We should explore who lived there and the forces shaping their lives. These landscapes are never just pretty pictures; they are sites of labor and conflict. Curator: Of course, there is much context we could elaborate on here. I'd propose it is also a study in light and shadow. See how Thier uses the pencil to simulate the effects of sunlight filtering through clouds, illuminating the textures of the landscape. This elevates it beyond a mere record. Editor: Still, consider the period this artwork was made. The Dutch Golden Age saw huge profits from global trade. Even rural scenes would have had a place in this structure. If we were to contextualize this art and exhibition with conversations around political, economic, and racial justice, these sorts of things need to be factored in. Curator: That's quite interesting! On one hand, it’s difficult to know an artist's intent, and so the meaning lies in how the shapes and techniques interact within the plane. You suggest that we read those signs through externalized social causes of which Thier might have no awareness, but regardless, thinking of how this artwork makes one feel, even to today’s causes, helps bring a better view of its presence. Editor: Indeed. By confronting art's entanglements, we can challenge systems that perpetuate inequity and marginalization, even from long ago!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.