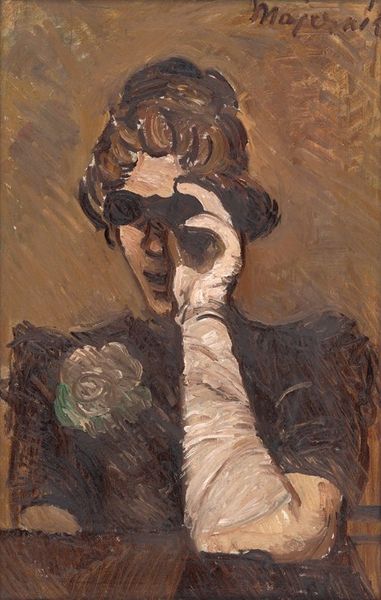

Dimensions: 68.8 cm (height) x 42.5 cm (width) (Netto)

Curator: What a brooding, smoky mood this artwork sets! Is she cold, or just lost in thought, do you think? Editor: Indeed! We are looking at "Sigrun," an oil painting from 1913 by the Norwegian artist Christian Krohg, currently held at the SMK, the National Gallery of Denmark. Krohg was a leading figure in the Skagen painters colony, known for their realism, but here there is an impasto that renders a rough emotive expression. I see much more than just cold in this piece. I think she's a portrait of suppressed emotion, given what we know of the rigid gender roles and expectations that affected women from that era. Curator: Yes, absolutely, there’s this contained intensity about her. The color palette does so much heavy lifting here, all greys and blacks. Even the light feels muted, as if a storm cloud is right overhead. Did Krohg leave behind any commentary on who Sigrun might have been? A muse, or perhaps someone from his family? Editor: Details about the sitter herself remain elusive. What strikes me is that even without a concrete backstory, the work evokes a particular feminine experience—one defined by constraint. The choice of dark, muted tones mirrors not just sadness, but the repression of identity itself. Krohg’s realism here serves a purpose: highlighting the real, tangible effects of social structures on women’s emotional and psychological states. We may consider the philosophy of that era concerning "feminine hysteria" and how art became a potent means of diagnosing such phenomena. Curator: That's such a great insight, yes, she really embodies the anxieties around women's mental states that were prevalent at the time! I'm also intrigued by the texture; you can really see the strokes, it’s a far cry from the smooth, idealized portraits of previous eras. Did Krohg work fast, do you think, or did he labor over each layer? It almost seems that the impasto creates the face—carving her out of paint like a sculpture, and maybe revealing something about her inner self. Editor: Exactly. It also speaks to something very human – an incompleteness. As women moved toward greater enfranchisement during this historical period, the canvas of “womanhood” remained unfinished and open to interpretation. These "realist" artworks show these complexities better than any purely figurative mode might provide. Curator: Thank you for such profound observations. I think next time I walk by this piece, I’ll be paying far more attention not just to what she might be feeling, but how that connects to these broader questions. Editor: Indeed. Let us hope such artworks serve to incite conversations not just of past repressions, but as to the means to achieving total equity today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.