Maria draagt korenaren op hoofd en is in gesprek met man met vogelkooi 1807 - 1823

0:00

0:00

drawing, watercolor

#

drawing

#

imaginative character sketch

#

quirky illustration

#

childish illustration

#

landscape

#

cartoon sketch

#

personal sketchbook

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

sketchbook drawing

#

watercolour illustration

#

genre-painting

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

cartoon carciture

#

sketchbook art

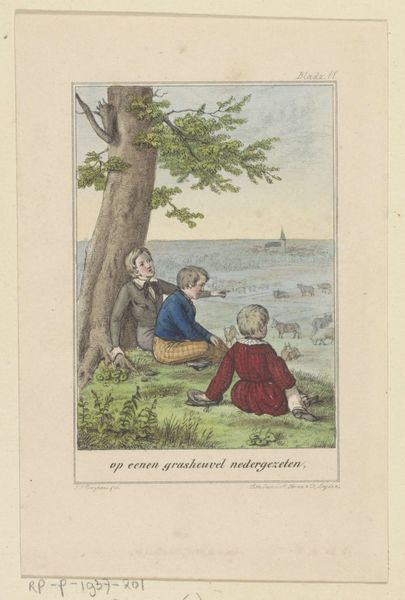

Dimensions: height 135 mm, width 86 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

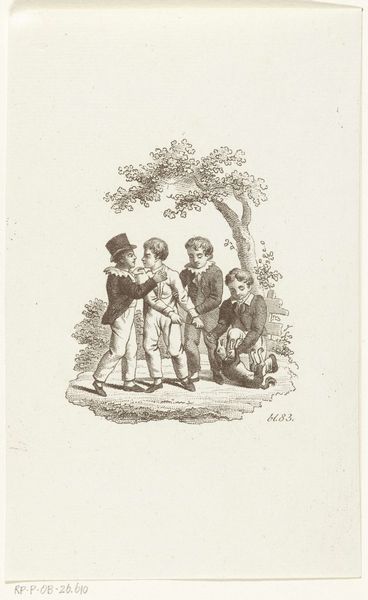

Curator: Looking at this whimsical image by Johannes Alexander Rudolf Best, dating from around 1807 to 1823, I'm struck by its narrative potential. It's titled "Maria draagt korenaren op hoofd en is in gesprek met man met vogelkooi" - "Maria carries corn stalks on her head and is in conversation with a man with a birdcage." It’s rendered in delicate watercolor. Editor: The first impression I get is of constraint – even sadness, strangely muted through these lightly applied watercolours. The materials don't give a lot away on the surface; but it’s hard not to be drawn in by that birdcage and its potential symbolism of repressed labor or potential freedom, perhaps? Curator: Absolutely, and thinking about gendered labor at this time, it becomes compelling. We see Maria, her labour made obvious by the heavy stalks, in dialogue with a man possessing what appears to be a domestic item – the birdcage. Is this image, therefore, reflective of broader themes around gender roles and economic disparity in early 19th century Netherlands? The burden she carries seems significant, the weight visible. Editor: Yes, her load contrasts sharply with his apparent idleness. He is *consuming* her labor, materially supported *by* her efforts. Consider too, the pigments. The soft wash could imply delicacy but could equally show cost constraints - revealing where value truly lies within a system of labour. Curator: That resonates deeply. His attire also marks him as someone with greater social standing, his clothing more complex than hers. And we must remember the role of Romanticism during that era—often idealising peasant life, whilst at the same time reinforcing class structures through depiction. It seems that Best engages with but possibly also complicates these power dynamics. Editor: Indeed. And think of what he owns: The cage itself represents *industry*. It *houses* another being, a resource, for his personal interest and to separate from its source. That he reclines alongside it hints at privilege. Curator: It forces us to question who has agency here. Perhaps Maria *is* challenging expectations? That wreath of flowers she is holding is a symbol of power. Or is this merely romanticisation, masking the harsh realities facing working-class women at that time? Editor: Whatever their interaction signifies, considering Best's choice of materials—drawing, watercolor—lends another layer, I find. These seemingly simple items have combined to suggest questions regarding socio-economic roles that remain pertinent even now. Curator: Yes, it truly underscores how historical artwork can spark incredibly contemporary discussions about societal pressures. Editor: Definitely. Thinking about it now, its gentle presentation still conceals hard hitting views of work, worth and control.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.