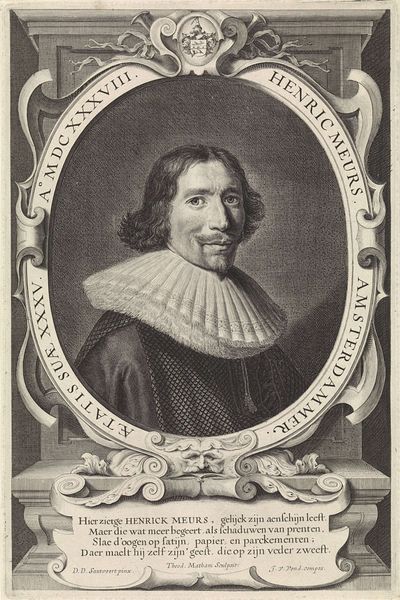

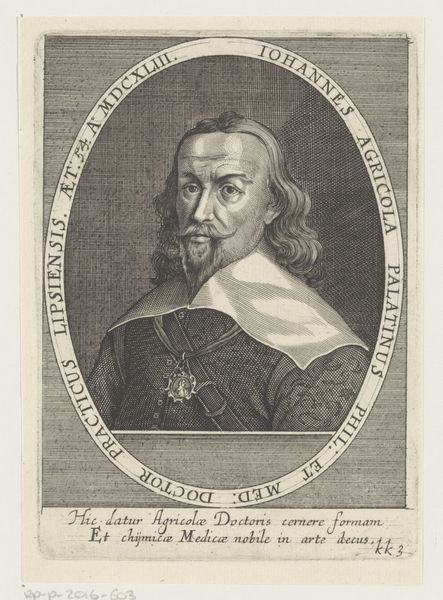

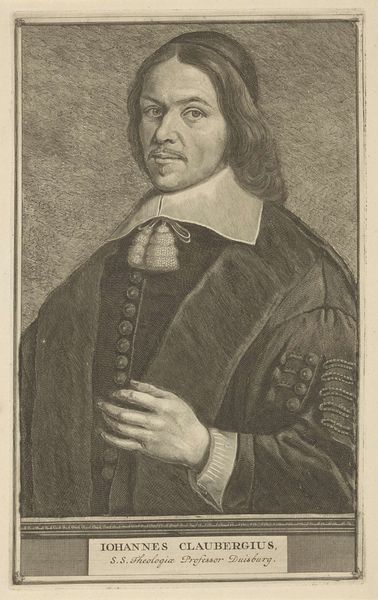

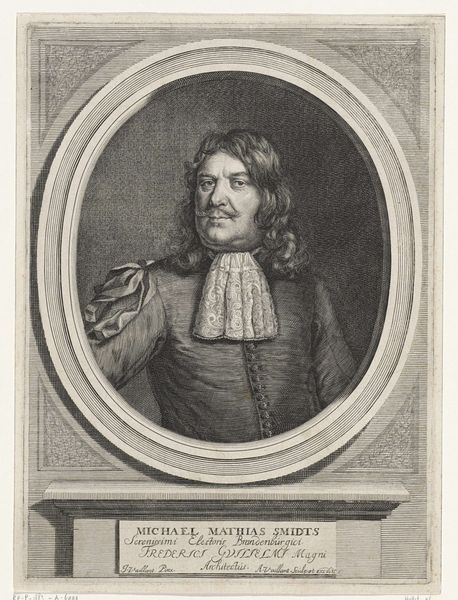

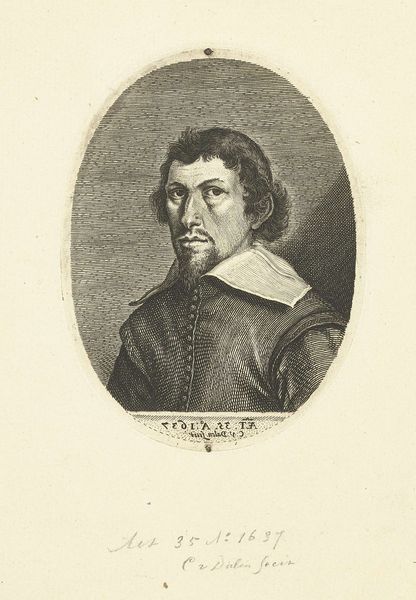

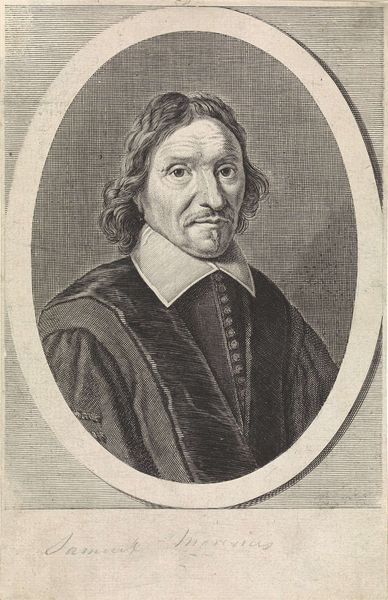

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

portrait reference

#

portrait drawing

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 302 mm, width 210 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

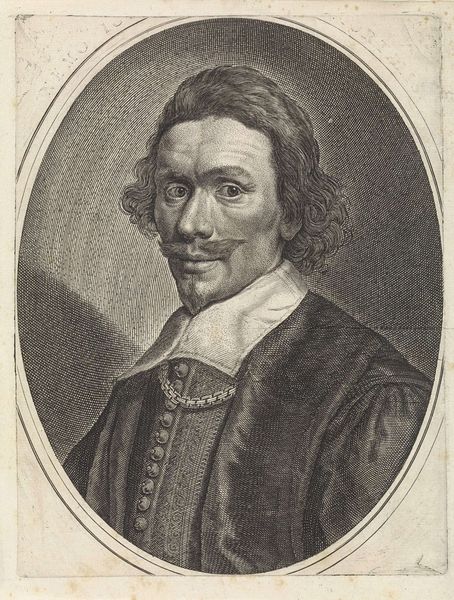

Editor: We're looking at a portrait of Theodorus Johannes Dirk Graswinckel, created sometime between 1636 and 1666 by Theodor Matham. It's an engraving, currently held at the Rijksmuseum. I'm really struck by how detailed the lines are, especially given the medium. What draws your attention in this piece? Curator: What interests me is the mechanics of its production. Engraving relies on a specific division of labour. Think of the artisan meticulously incising lines into a copper plate, creating a matrix to produce identical multiples. This process democratises image production, placing portraits – usually exclusive commodities – within reach of a wider audience. Note also the materiality; ink, paper, and the press itself become central to the meaning. The final print isn't simply a representation, but the product of specific processes and relationships. What do you make of the imagery surrounding the portrait itself? Editor: I see symbolic objects…scales of justice, a rooster…Do those relate to his profession or status? Curator: Precisely. These weren’t arbitrarily chosen, but carefully designed to construct an image of power and authority tied to the sitter's identity. However, considering the socio-economic background of this print, were these images truly impactful, or did their inherent symbolic power get somehow ‘lost in translation’ due to the industrialisation of its making? Editor: That's a fascinating point! It really makes you think about how the meaning changes depending on how accessible the art is and who is making it. Curator: Indeed. Examining art through its materiality and production opens a window into the complex relationships between artist, patron, process, and ultimately, its audience. Editor: This perspective makes me appreciate the work on a different level, by understanding its material process.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.