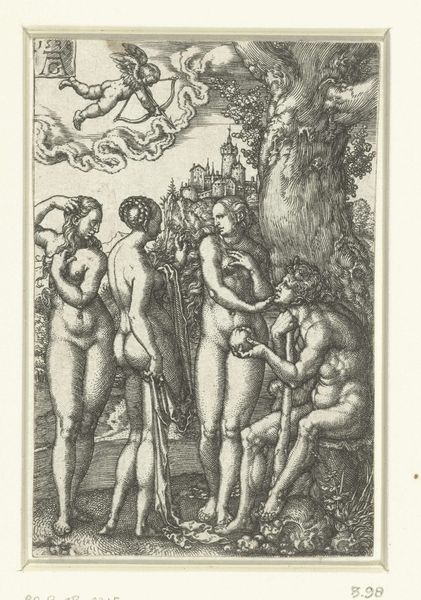

etching

#

medieval

#

etching

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

nude

Dimensions: height 196 mm, width 164 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This etching, "Vrouwenbad", or "Women's Bath," dates from somewhere between 1490 and 1500, crafted by the enigmatic Monogrammist PM of the 15th century. What springs to mind when you first see it? Editor: An uncanny sense of witnessing something intensely private, yet displayed with an almost confrontational directness. The figures seem caught in their own world, and the varying conditions of the women presented are evocative and, dare I say, even political in their own way. Curator: It is fascinating how many different lives, different ages of women's lives are captured, side by side! Take the headdress. While the nudity is striking, such headwear would have indicated status, perhaps specifically identifying married women. What do you make of it? Is there a connection between headwear and status that impacts our reading of this artwork today? Editor: Absolutely, status plays a role. The bath, often a communal space in the Middle Ages, was a place of ritual but also social interaction, and I suspect that while ostensibly this depicts women at their most physically exposed, it simultaneously reinforces a hierarchical order—revealing power structures even, or especially, in moments of intimacy. These bathhouses were rife with power dynamics both for good, women bonding, and ill, exploitation, which should never be divorced from artwork readings. Curator: Yes, and look closely at the children; how they seem to directly confront the viewer. It begs the question: what meanings do they embody? Childhood innocence, perhaps? Or are they commentary of legacy and tradition? And the clear emphasis on bare, pregnant bodies...It makes me think about ancient Roman bathhouses; fertility rituals might have been mixed into daily washing, wouldn't you agree? Editor: Certainly, I think that the intermingling of nude pregnant women in Northern Renaissance Europe, specifically, would invite readings around labor, around anxieties of reproduction. These spaces can be read as places to reinforce the 'traditional' roles of women, not outside them. It reinforces a message. Curator: Thank you! It certainly illuminates new pathways for reflection. Editor: My pleasure. Every piece reveals different elements of its cultural moment each time we engage.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.