Copyright: Public domain

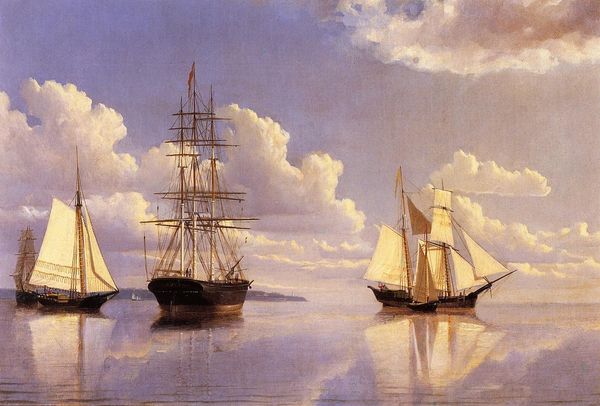

Editor: So, here we have William Bradford's "East River Off Lower Manhattan," painted in 1862 using oil paint. There’s a sort of calm, almost eerie, stillness to it with all these ships just… there. What stands out to you about this piece? Curator: Well, beyond the technical skill evident in Bradford’s rendering of the light and water, I'm particularly drawn to the context. Consider the date, 1862. The Civil War is raging. What does it mean to depict New York as a center of calm commerce during such turmoil? This image functions as a powerful, if perhaps unconscious, statement. Editor: A statement of what, exactly? Curator: A statement about the North's economic power and endurance. This painting becomes a form of visual propaganda, subtly reinforcing the idea that despite the conflict, life, and more importantly, trade, continues. Bradford focuses on mercantile activity instead of showing, say, military ships or soldiers. What kind of statement is he trying to convey, and who is his intended audience? Editor: So, it's not just a pretty picture, but a kind of… economic boast? It makes me wonder if that seemingly calm water is actually hiding a lot of anxiety about the war's outcome. Curator: Precisely. And who gets to participate in this "calm" commerce? Whose prosperity is being visually celebrated here, and at whose expense? Understanding that this scene is taking place against the backdrop of the Civil War and the economic inequalities of the time opens up new avenues for interpretation. It underscores how art can participate in and shape political and social discourse. Editor: I never would have looked at it that way, but it makes the image so much more complex and, honestly, interesting. Thanks for the insight. Curator: My pleasure. Seeing art as more than just aesthetics – as active participant in history - changes everything.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.