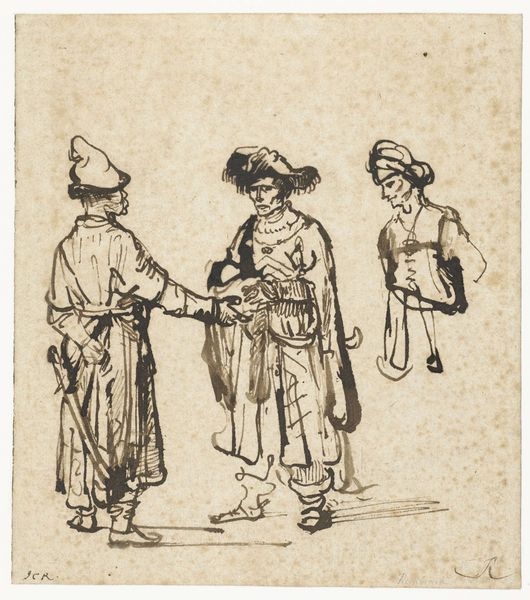

Boy with a Dog, Two Men Talking and a Profile Head of a Man c. 1657 - 1662

0:00

0:00

rembrandtvanrijn

Rijksmuseum

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

dog

#

incomplete sketchy

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

watercolour illustration

#

sketchbook art

Dimensions: height 94 mm, width 131 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. Before us, we have Rembrandt van Rijn’s pen and ink sketch from circa 1657 to 1662 entitled "Boy with a Dog, Two Men Talking and a Profile Head of a Man" at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It strikes me as incredibly intimate. The sketchy quality lends it the feeling of peering directly into Rembrandt’s personal sketchbook, catching fleeting observations of daily life. Curator: Exactly! It gives us a raw look into Rembrandt's process. Think about the materiality of 17th century drawing: paper carefully toned, precious inks… Sketchbooks would have been a key aspect of the entire workshop production system and his pedagogical strategy for students. It democratizes art creation in a way, doesn’t it? Editor: It does. And when you consider Rembrandt's social standing – an artist who achieved fame but also experienced bankruptcy – this glimpse into everyday interactions humanizes him. Notice how the composition subtly directs our gaze. It starts with the boy and his dog, guides us to the men conversing, and ends with that almost-hidden profile. Curator: Indeed. Consider the politics of representation during this period. Depictions of common people were gaining prominence. Rembrandt, by focusing on these subjects, implicitly elevates their status and offers social commentary. Also, did Rembrandt himself prepare his drawing implements or was it left to his students? Who decided on the ratio between ink and water and where does labour reside in this drawing? Editor: I see your point. The act of creating such art was deeply embedded in the social fabric, and this image perhaps captured a pivotal moment of evolving public consciousness around artistic processes and image-making. The fluidity of the line work in contrast to some carefully considered compositional moments adds to its significance, doesn't it? Curator: Precisely! These unassuming subjects reflect shifts within 17th-century Dutch society itself. The rising merchant class, new attitudes about leisure, are all embodied right here. It gives us insight into art’s contribution to broader conversations on community. Editor: It is quite amazing how so much is conveyed in so little. I now find the simplicity of the ink and paper even more compelling. It embodies more than just daily life of 17th century Holland and captures humanity as a whole. Curator: Agreed. It underscores art’s potential to be a tool for engagement.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.