photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

photography

#

watercolor

#

realism

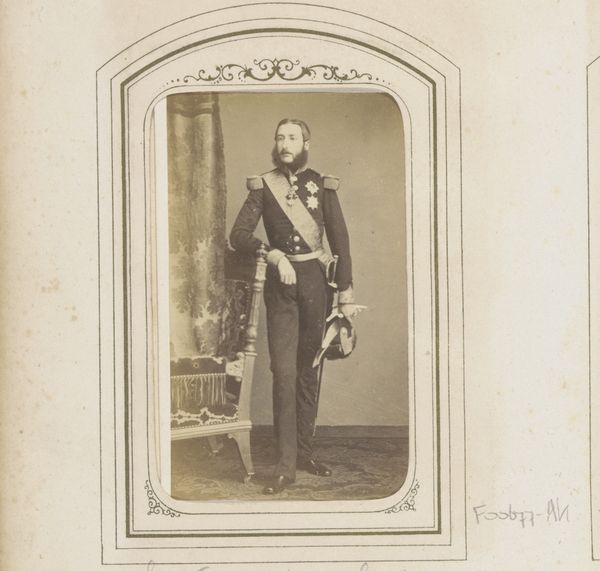

Dimensions: height 137 mm, width 95 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

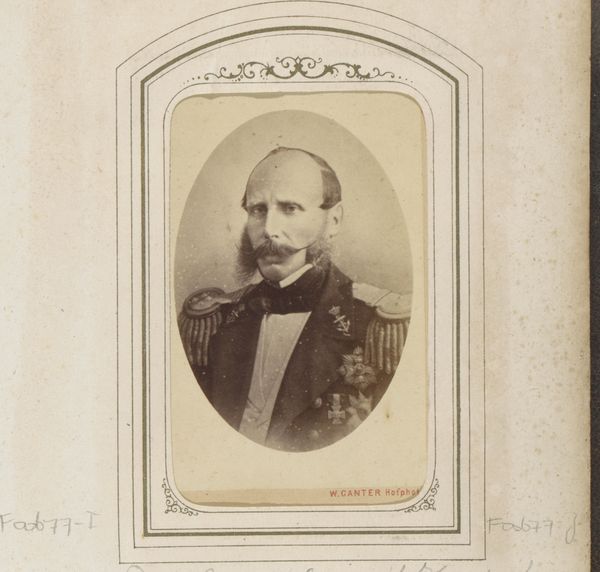

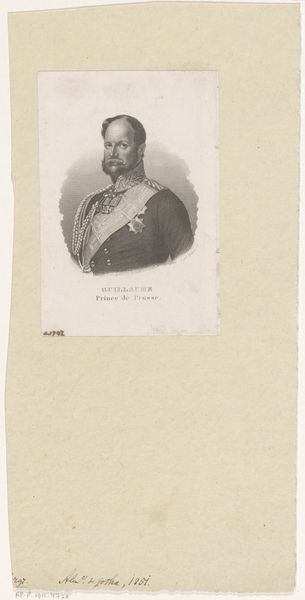

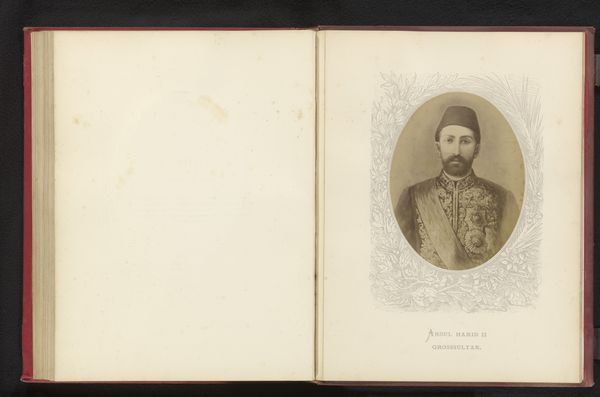

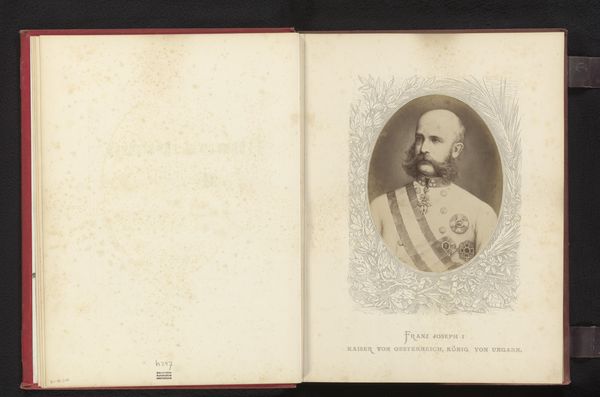

Curator: The sepia tones lend an immediate sense of austerity. It’s a rather imposing, almost melancholy portrait. Editor: It is. This is a photographic portrait of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria, created sometime between 1870 and 1880. The portrait is mounted in a bound volume, giving it a sense of permanence. Note the materiality, though – it looks almost like a watercolor, but it’s a photograph, a process of capturing light, manipulated and preserved through chemical processes and paper. Curator: Right. And let’s not forget that this process makes the sitter's features seem softer. The blurring obscures his social and political role as Emperor of Austria; but, for the everyday person who came across it, perhaps they were able to make some sort of deeper connection with him through his softer rendering. The photograph flattens class structures even while picturing someone at the pinnacle of one. Editor: An interesting paradox, definitely. Considering the social unrest brewing in the Austro-Hungarian empire during that period, portraying a softened leader is quite telling. Note the framing – oval and bordered – further objectifying Franz Joseph I, reminding people that at the end of the day, he is indeed of another class. The meticulously groomed beard is especially poignant when we think of other famous, world leaders. Curator: The production and consumption of photographs served a function in maintaining the myth of the emperor but they were a technology that could and would be used against the structures of power and class. I wonder, do you think this was some calculated, self-conscious image control at play, or pure vanity? Editor: I think it's a complex intertwining of both. A ruler's image is never purely for personal consumption, but an intricate tool designed for wielding power in multiple, interconnected spheres. It invites questions around national identity, gender, and how an image can both solidify and subvert existing power dynamics. Curator: The material evidence, here, is less about the person pictured but more about a shifting social and political landscape where visibility was changing for everyone through industrial production. Editor: True. By examining these details we've uncovered a microcosm of the political machinations behind image-making. It really showcases the way that, on one hand, art might have the illusion of revealing someone, but truly is revealing historical truths.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.