painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

female-nude

#

expressionism

#

nude

#

portrait art

#

expressionist

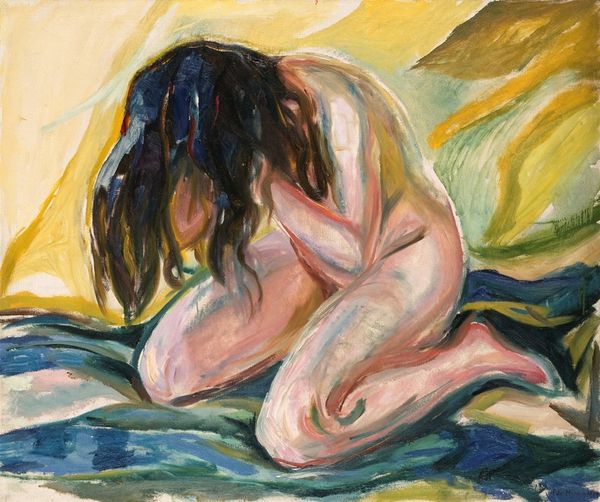

Dimensions: 80 x 100 cm

Copyright: Public domain

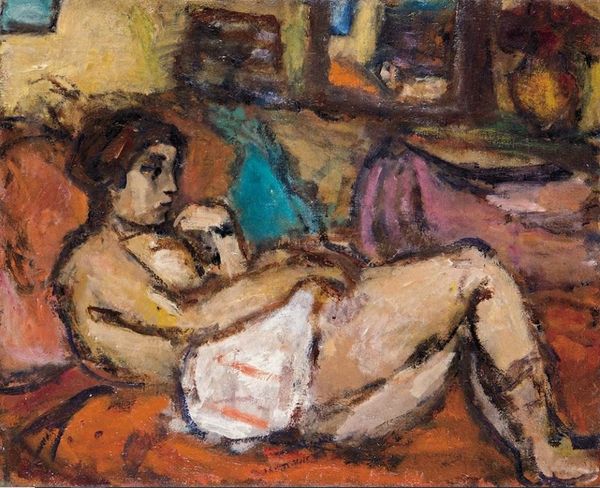

Curator: So here we have Edvard Munch's "Nude I", painted in 1913. It's currently housed at the Munch Museum in Oslo, a striking example of his exploration of the human form and emotional states rendered in oil on canvas. Editor: It's funny how confronting it is, even though she's turned away. That turbulent hair, hiding the face—you feel what, shame? Anguish? The dark palette seems to swallow the figure whole, really highlighting that heavy mood. Curator: It is arresting, isn’t it? Munch’s nudes often delve into complex territories beyond mere representation. In its time, this piece challenges bourgeois expectations of ideal femininity; Munch seems to be looking at his sitter with a darker psychological eye, beyond the visual alone. We see her vulnerability, perhaps even a critique of the objectification inherent in traditional nude portraiture. Editor: Absolutely. And there's that dichotomy with the plush red sofa, almost like a stage, setting up the female form. However, the execution just cuts any possible erotic charge off at its root. This is less about lust, more about an exploration into psychic spaces. Curator: It’s remarkable how the brushwork contributes. See the almost violent strokes around the hair and torso? Those strokes become expressive tools reflecting emotional turbulence that invite us to engage empathetically. And this particular painting came after a period of intense mental health struggles for Munch. Editor: You know, I often wonder how audiences would have reacted to this back then? Scandalized perhaps, by such a frank, almost raw depiction? And do you think Munch, when producing such work, was consciously trying to stir something up or truly trying to get a psychological message across. Curator: Given the socio-political climate and the development of modern psychology during the period, it's safe to assume that he meant to make some commentary, not necessarily scandalizing, but forcing the society to think more deeply about gender. But that said, what do any of us know? The work's evocative power persists today, raising endless queries for its viewers. Editor: That is the strange enduring mystery of great art: like a good psychoanalyst, its power comes not only from any answers, but also from those very unresolved feelings it leaves us holding, isn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.