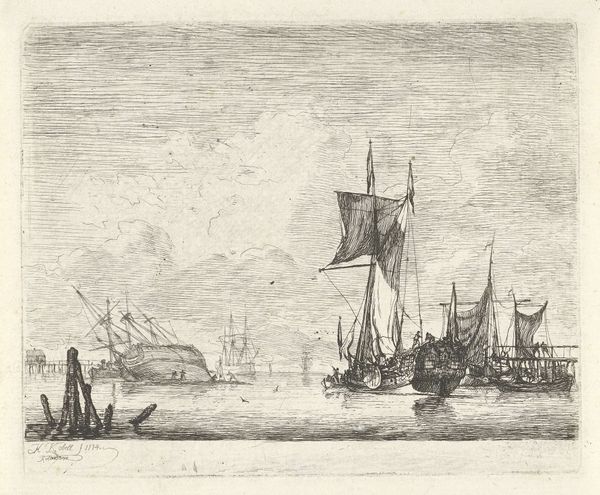

print, etching, engraving

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

line

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 89 mm, width 140 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

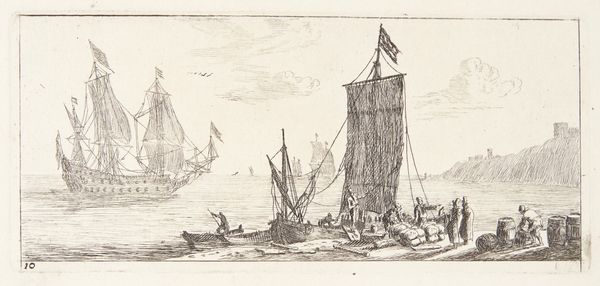

Curator: Before us, we have Hendrik Kobell’s "Riviergezicht met vissers," or "River View with Fishermen," an etching and engraving dating roughly between 1761 and 1779, here at the Rijksmuseum. It presents a bustling riverside scene. Editor: My initial impression is how immediate and raw this scene feels, despite being an etching. You can almost smell the salt and hear the cries of the workers. The artist has really captured a specific moment. Curator: It's precisely that immediacy that’s compelling. Consider the labor involved: the processes of etching and engraving—applying the resist, incising the lines into the metal plate, applying ink and then using intense physical pressure to transfer that image to paper. This piece really underscores the means of production. The lines aren’t just lines; they’re traces of labor, capturing not just a scene, but the act of creating. Editor: Absolutely, and I'd also argue that the print itself plays a role in democratizing access to this river view. Instead of being confined to wealthy patrons, images like this circulate, informing a broader public about Dutch maritime power, industry, and even class structure. It highlights how vital images were in shaping public consciousness in this era. What we might call propaganda of the everyday, subtly celebrating labour. Curator: I’m thinking about what the presence of numerous boats means, though, when we factor in the labor invested in ship building and maritime activity in the Golden Age. It tells a more nuanced narrative, perhaps about the economics that affect that class. Editor: It is subtle, but in this, Kobell highlights how this river functions as a site of exchange, where resources converge and connect. It’s an argument for Dutch global positioning told on a smaller scale. Curator: The work makes the process of consumption explicit, though, even highlighting its cultural place via an accessible format like an etching that brings it to more homes and people than painting likely would. Editor: I’m intrigued by how the print participates in constructing and solidifying Dutch identity by glorifying and making ubiquitous the very sites of labor on which that identity and national pride was built. It is almost a document of a cultural and political positioning. Curator: Well, viewing it in that light certainly enhances one’s perspective, providing much richer socio-economic nuance. Editor: Indeed. I come away appreciating how cultural imagery actively shapes historical narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.